Click for larger image

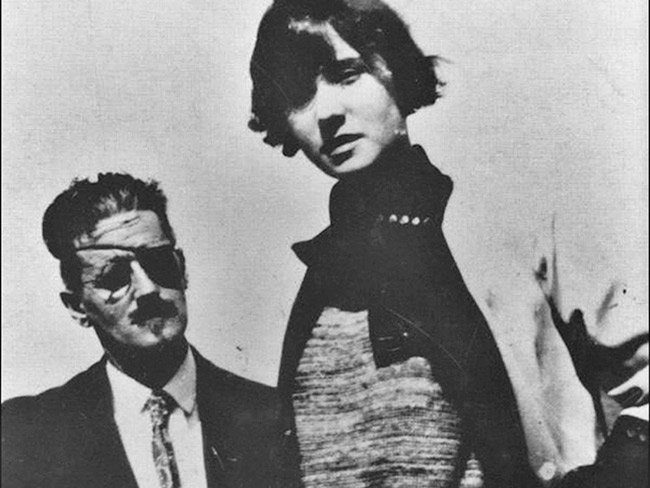

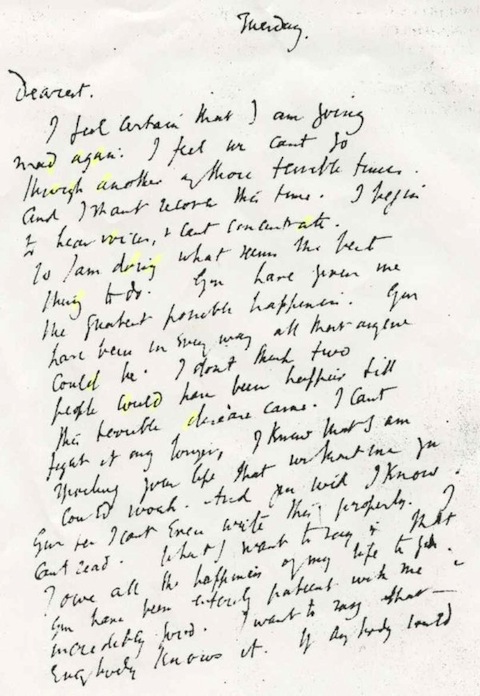

Important twentieth-century painters, as every student of art history learns, didn’t tend to sail smoothly through existence. Those even a little interested in famed Mexican self-portraitist Frida Kahlo have heard much about the travails both romantic and physical she endured in her short life. But in this lesser-known instance, another artist suffered, and Kahlo offered the solace. Available to view from Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, we have here a letter Kahlo sent to Georgia O’Keeffe, painter of blossoms and southwest American landscapes (and more besides), on March 1st, 1933. At that time, O’Keeffe, who the year before had struggled and failed to complete a mural project for Radio City Music Hall on time, lived through the aftermath of a nervous breakdown which had hospitalized her (diagnosis: “psychoneurosis”), sent her to no less remote a locale than Bermuda to recuperate, and prevented her from painting again until 1934.

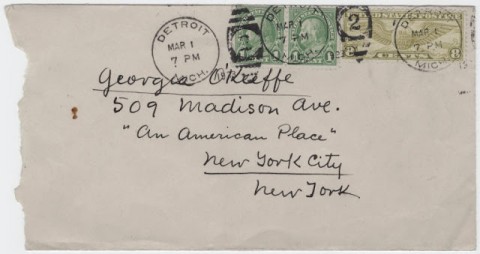

Kahlo’s letter, sent from Detroit where her muralist husband Diego Rivera had taken a commission for 27 frescoes at the Institute of the Arts, runs as follows:

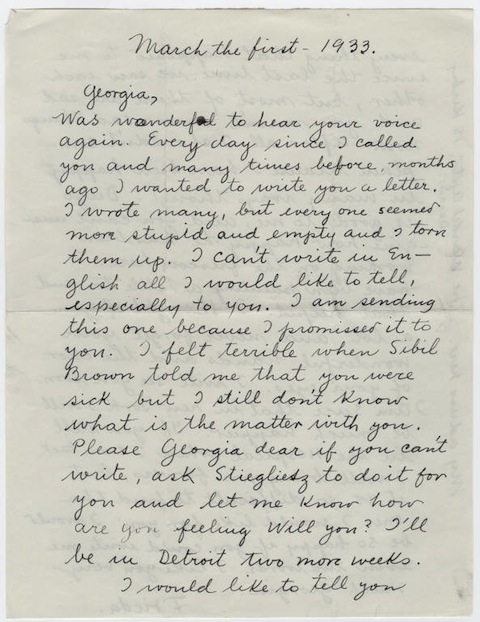

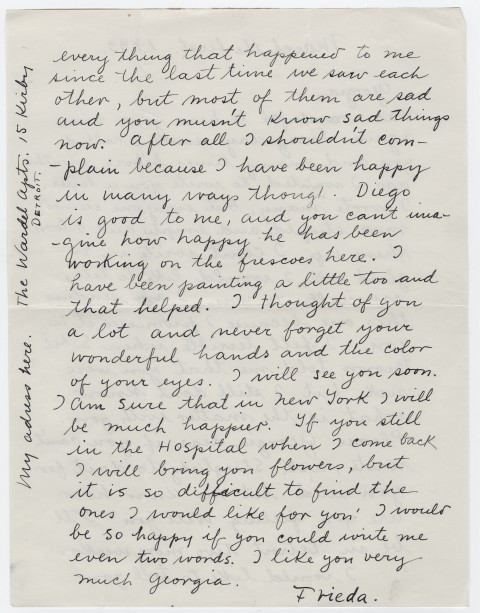

Georgia,

Was wonderful to hear your voice again. Every day since I called you and many times before months ago I wanted to write you a letter. I wrote you many, but every one seemed more stupid and empty and I torn them up. I can’t write in English all that I would like to tell, especially to you. I am sending this one because I promised it to you. I felt terrible when Sybil Brown told me that you were sick but I still don’t know what is the matter with you. Please Georgia dear if you can’t write, ask Stieglitz to do it for you and let me know how are you feeling will you ? I’ll be in Detroit two more weeks. I would like to tell you every thing that happened to me since the last time we saw each other, but most of them are sad and you mustn’t know sad things now. After all I shouldn’t complain because I have been happy in many ways though. Diego is good to me, and you can’t imagine how happy he has been working on the frescoes here. I have been painting a little too and that helped. I thought of you a lot and never forget your wonderful hands and the color of your eyes. I will see you soon. I am sure that in New York I will be much happier. If you still in the hospital when I come back I will bring you flowers, but it is so difficult to find the ones I would like for you. I would be so happy if you could write me even two words. I like you very much Georgia.

Frieda

“Clearly Kahlo hoped for a deeper friendship, or perhaps more, with O’Keeffe, when she and Diego went to New York a few weeks later,” writes Sharyn Rohlfsen Udall in Carr, O’Keeffe, Kahlo: Places of Their Own. “From there, she wrote to a friend on 11 April (by which time O’Keeffe had gone to Bermuda to convalesce) that because of O’Keeffe’s illness there had been no lovemaking between them that time. A boastful exaggeration of their closeness? Knowing Kahlo’s predilection for sexual hyperbole, this seems likely.”

via A Piece of Monologue, A Writer’s Ruminations

Related Content:

The Real Georgia O’Keeffe: The Artist Reveals Herself in Vintage Documentary Clips

Watch Moving Short Films of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera at the “Blue House”

Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera Visit Leon Trotsky in Mexico, 1938

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on literature, film, cities, Asia, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.