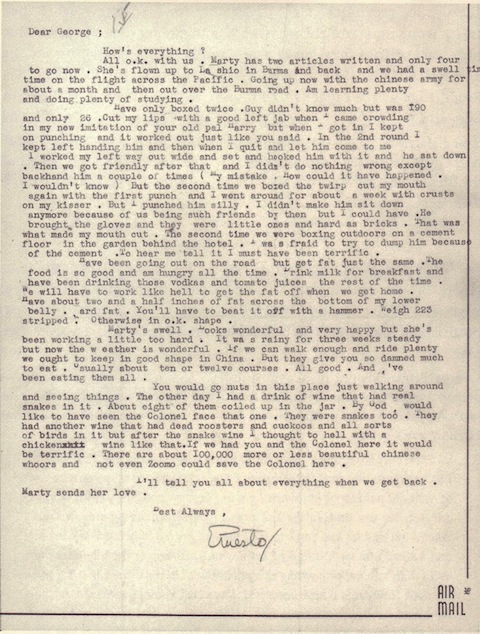

Every successful artist must master the art of accepting rejection. “Fail better,” said Beckett in his grim euphemism for perseverance. “I love my rejection slips,” wrote Sylvia Plath in every hopeful poet’s favorite quote. “They show me I try.” Plath—who also wrote “I am made, crudely, for success”—collected scores of rejection letters, receiving them even after the considerable success of 1960’s The Colossus and Other Poems. The 1962 letter above (click here to view in a larger format), from The New Yorker, doesn’t exactly reject a Plath submission, but it does recommend cutting the entire first section of “Amnesiac” and resubmitting “the second section alone under that title.” “Perhaps we’re being dense,” demurs editor Howard Moss.

The rejection must have been all the more painful since Plath was under a contract with the magazine, which entitled her to “an annual sum for the privilege of having a ‘first reading’ plus subsequent publishing rights to her new poetry,” Plath scholars tell us. And yet “much to her distress she mainly received rejections during November and December 1962.” The poem was eventually broken in two, with the first half published as “Lyonnesse,” but not by Plath herself but by publishers after her death. Hear Plath read the full poem as she intended it in her edition of Ariel, above.

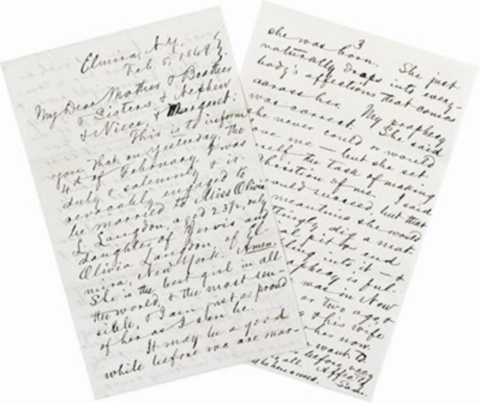

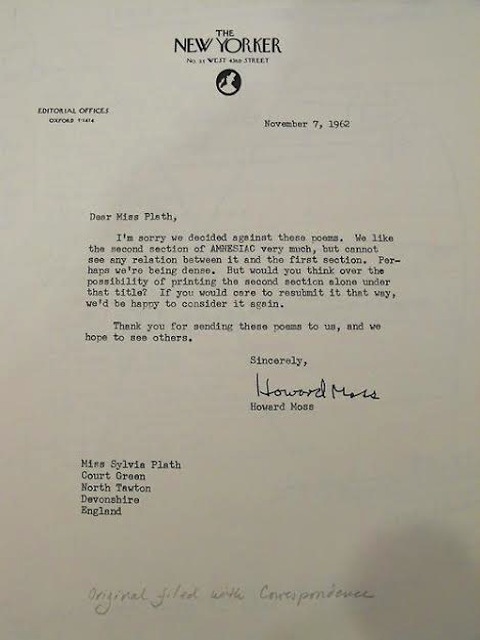

Kurt Vonnegut received an impersonal, and it would seem, long-overdue rejection letter from editor of The Atlantic Edward Weeks in 1949. Weeks writes breezily that he found Vonnegut’s “samples” during the “usual summer house-cleaning,” announcing its slush-pile status. Weeks does at least give the impression that someone, if not him, had read Vonnegut’s submissions. The aspiring writer was 27 years old, striking out “just a few years after surviving the bombing of Dresden as a POW,” Letters of Note informs us, and still twenty years away from publishing his groundbreaking novel Slaughterhouse Five. Letters of Note also provides us with the transcript below for the badly faded typescript.

The Atlantic Monthly

August 29, 1949

Dear Mr. Vonnegut:

We have been carrying out our usual summer house-cleaning of the manuscripts on our anxious bench and in the file, and among them I find the three papers which you have shown me as samples of your work. I am sincerely sorry that no one of them seems to us well adapted to for our purpose. Both the account of the bombing of Dresden and your article, “What’s a Fair Price for Golden Eggs?” have drawn commendation although neither one is quite compelling enough for final acceptance.

Our staff continues fully manned so I cannot hold out the hope of an editorial assignment, but I shall be glad to know that you have found a promising opening elsewhere.

Faithfully yours,

(Signed, ‘Edward Weeks’)

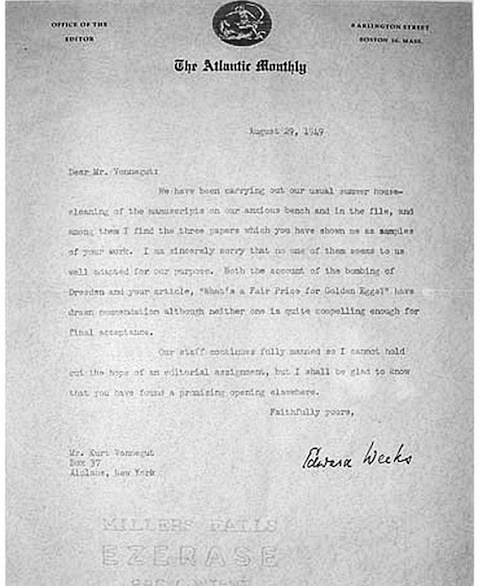

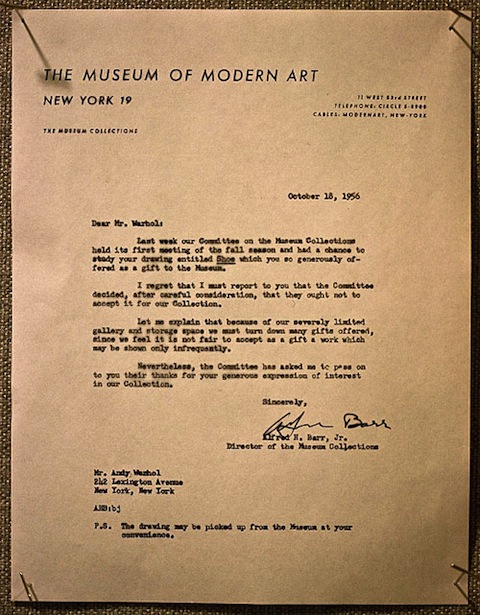

Of course visual artists are not immune. Andy Warhol received the above rejection letter from New York’s Museum of Modern Art when he attempted to donate a drawing in 1956. To its later chagrin, the museum wouldn’t let him give his work away:

Last week our Committee on the Museum Collections held its first meeting of the fall season and had a chance to study your drawing entitled Shoe which you so generously offered as a gift to the Museum.

I regret that I must report to you that the Committee decided, after careful consideration, that they ought not to accept it for our Collection.

The Warhol rejection circulated a few years ago after the MoMA tweeted Letters of Note’s post on it (read the full transcript there). Its most galling feature: a postscript that reads, with dismissive courtesy, “The drawing may be picked up from the museum at your convenience.”

Related Content:

Gertrude Stein Gets a Snarky Rejection Letter from Publisher (1912)

No Women Need Apply: A Disheartening 1938 Rejection Letter from Disney Animation

New Yorker Cartoon Editor Bob Mankoff Reveals the Secret of a Successful New Yorker Cartoon

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness