Image via Wikimedia Commons

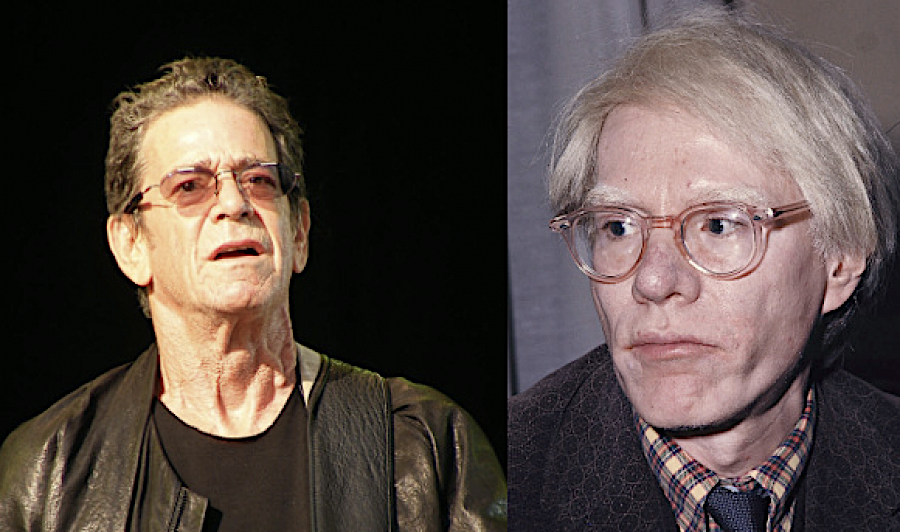

It’s every researcher’s dream: that somewhere among the pile of materials lies gold, an undiscovered masterpiece, or an unknown piece to a puzzle that complicates conventional knowledge. That’s what Cornell University’s Judith Peraino discovered while going through some of the 3,500 cassettes in the Andy Warhol archive. Here she found a mix-tape cassette that Lou Reed had made for Andy in the mid-seventies, with one side a selection of songs from recent live gigs, the other side containing 12 unknown and unreleased songs by Reed, accompanied by only his guitar, recorded at home in New York City.

Labeled “The Philosophy Songs (From A to B and Back),” the songs are Reed’s response to Warhol’s 1975 book The Philosophy of Andy Warhol: From A to B and Back Again, which his mentor had sent to Reed in galley proof. Their relationship was always difficult. After an unpleasant breakup after the Velvet Underground came out from under Warhol’s shadow, the two never worked together again. But they kept in touch in the way that certain bitter exes do: keeping it cordial, possibly considering working together again, then realizing why they broke up in the first place.

Prof. Peraino surmised that the tape is related to a musical Warhol wanted to create with Reed based on Warhol’s book. And in fact Reed uses passages from the book as jumping off points for the lyrics, she found. There’s a song each about “fame, sex, and the business of art,” and two about drag queens. But Reed used other songs to criticize Warhol for his seeming indifference to the deaths of Factory stars Candy Darling and Eric Emerson, adding that he should have died after being shot in 1968. Reed then apologies to Warhol at the end of the song.

Because her research was about the beginnings of mixtape culture, queerness, and Warhol’s endless boxes of cassettes, she is excited about both sides of the tape. Mixtapes, she explains, were a way for people to communicate complex emotions without having to simply write them down. Songs strike emotional chords in so many ways.

The tape “is an example of Lou Reed curating himself, putting together an ideal set list for Andy Warhol,” Peraino says in Cornell’s video interview. “I see the message of the tape as being both courtship and breakup in a sense. The one side is saying, look at me, what I’ve able to do this year…and now look at you.”

Apart from a 30-second excerpt, found on Variety’s web page, there are no current plans to release something so rough, and with so many rights issues at stake.

Lou Reed did go on to make something similar however, when in 1990 he wrote Songs for Drella with fellow Velvet John Cale.

Related Content:

Andy Warhol Demystified: Four Videos Explain His Groundbreaking Art and Its Cultural Impact

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the artist interview-based FunkZone Podcast and is the producer of KCRW’s Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, read his other arts writing at tedmills.com and/or watch his films here.