If high school English teachers can challenge skeptical students to cultivate an appreciation for Shakespeare and poetry with rap-based assignments, might the reverse also hold true?

Many aficionados of high culture turn up their noses at rap, believing it to be a simple form, requiring more braggadocio than talent.

Estelle Caswell, rap fan and producer of Vox’s Earworm series, may get them to rethink that position with the above video, showcasing how great rappers assemble rhymes.

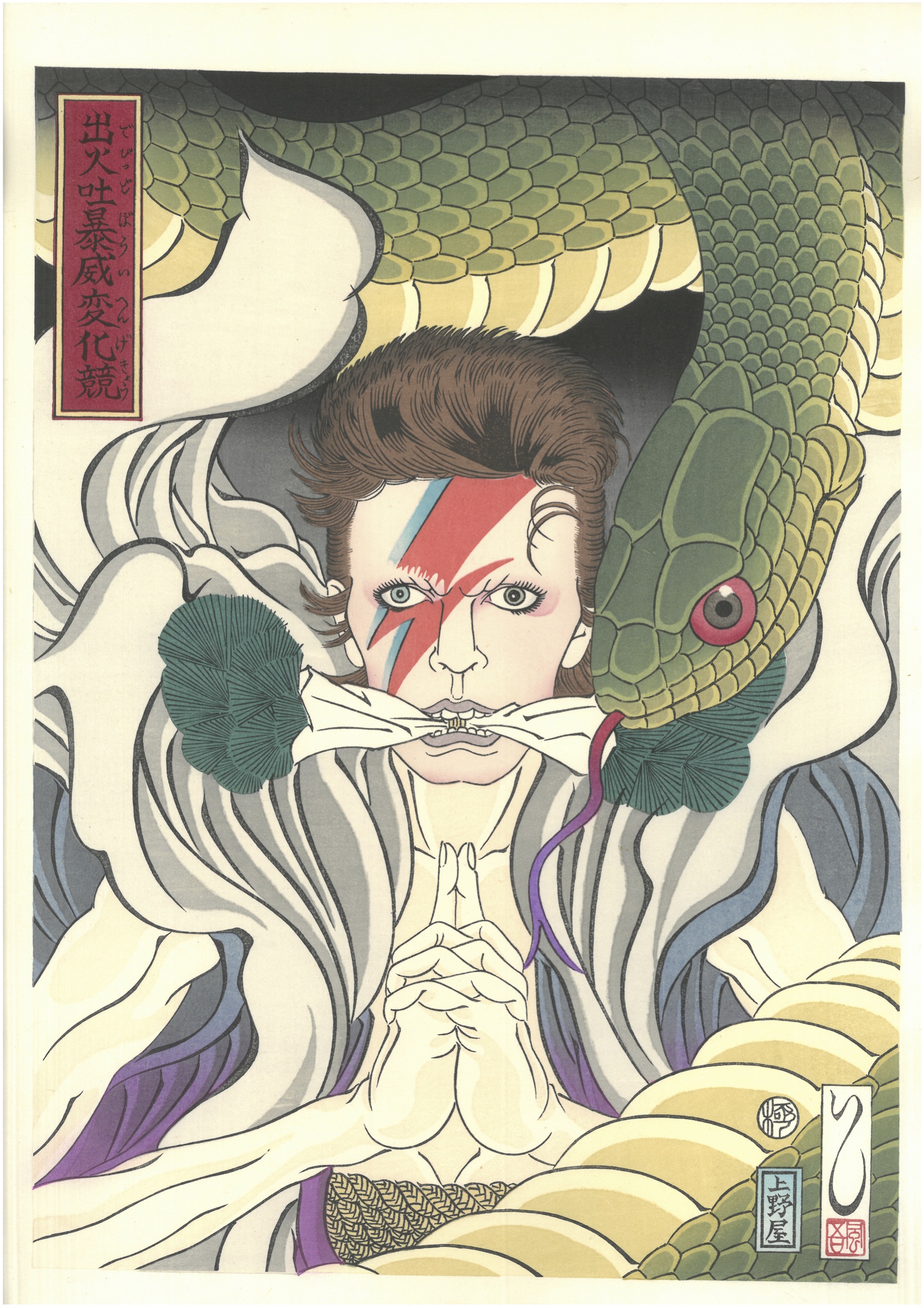

Caswell uses visual graphing to explain the progress from the A‑A-B‑B scheme of early rapper Kurtis Blow’s “The Breaks” (1980) to the complex and surprising holorimes of her personal favorite, MF DOOM.

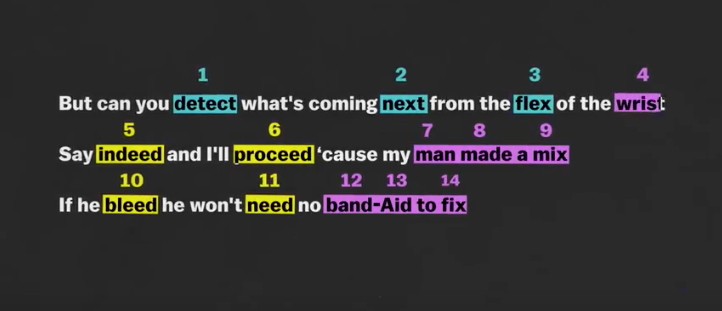

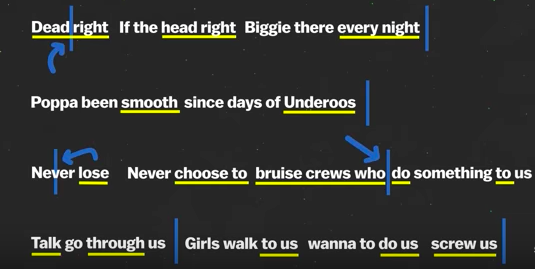

To appreciate her visual breakdowns, you must understand that raps can be scored like traditional music. Here the bar reigns supreme—each bar consisting of four beats. The further out we go from rap’s origins, the more its practitioners play with placement and rhyme.

Above are some lyrics from Eric B. and Rakim’s 1986 cut, “Eric B. Is President,” featuring internal rhymes highlighted in yellow and multi-syllabic rhymes picked out in pink. You’ll also find them escaping the tyranny of the bar line, continuing the rhyme on the first beat of the next bar.

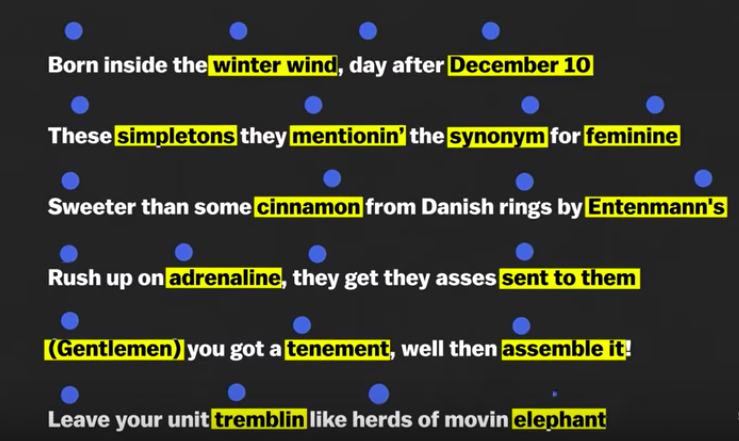

Caswell is so intent on examining the late Notorious B.I.G.‘s “Hypnotize,” that she overlooks a rather sizable elephant in the room, the misogynistic POV behind those en and oo sounds.

Shortly thereafter, Mos Def ups both the rhyming game and the feminist accountability, by stuffing his compositions with multi-syllabic words and phrases that sort of rhyme—cinnamon, Entenmann’s, adrenaline and “sent to them.”

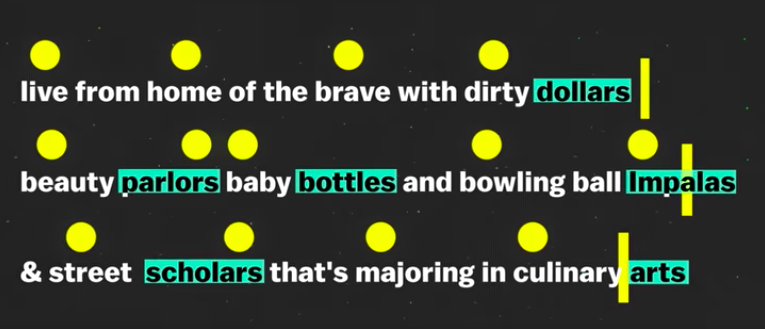

Meanwhile, Andre 3000 is playing with varying the accent of his rhymes, relative to the beat and bar, rather than committing to a predictable thudding.

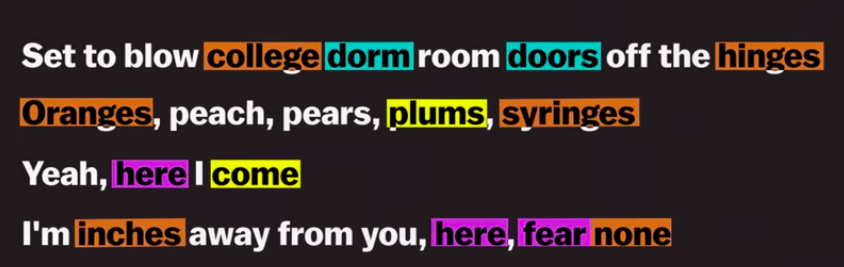

Eminem, who has the distinction of penning the first rap to win an Academy Award, places a premium on narrative, and refuses to concede that nothing rhymes with orange.

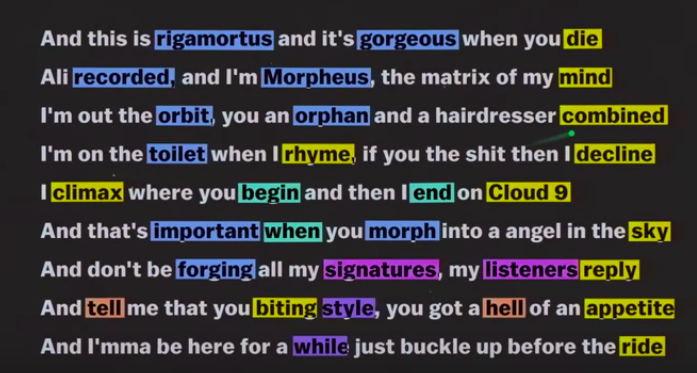

Current chart topper Kendrick Lamar’s galloping “Rigamortis” establishes a musical motif that Caswell compares to Beethoven’s famous fifth.

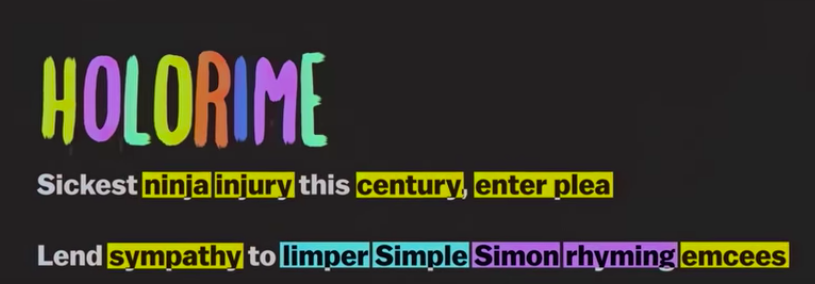

MF DOOM kicks the ball further down the court with double entendres, wordplay and a willingness to steer clear of the expected “b word.”

Listen to a Spotify playlist of the songs referenced in the video.

Delve further into the subject by reading the thoughts of rap analyst Martin Connor, whom Caswell credits as a sort of beacon.

Related Content:

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday.