All images courtesy of Lori Pond

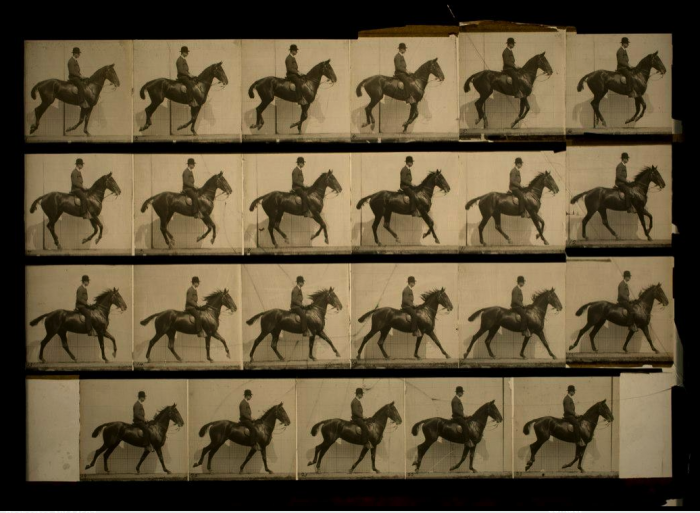

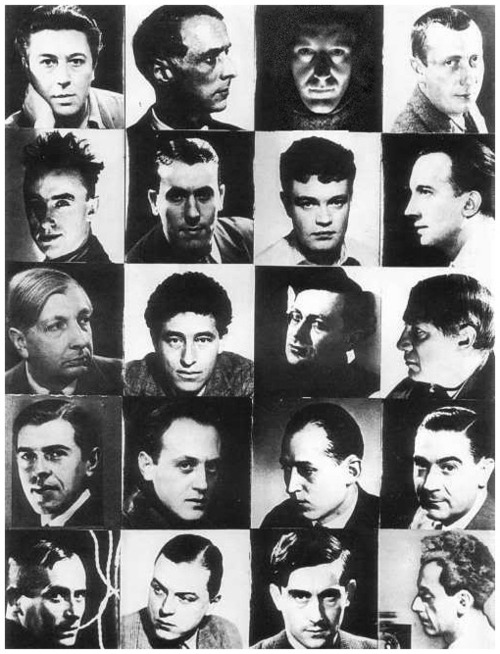

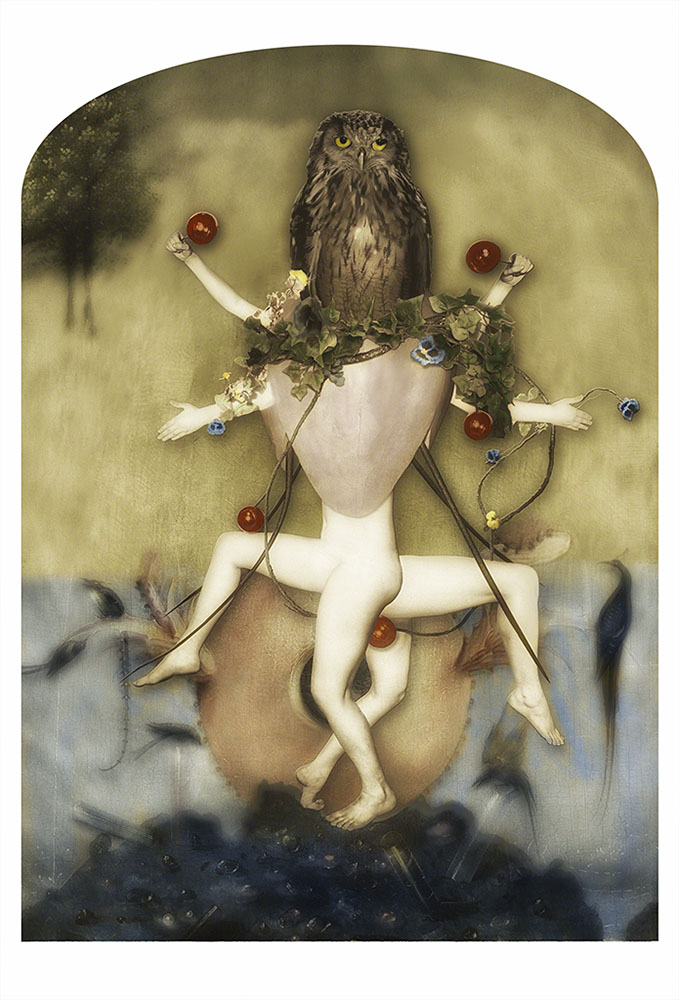

It is not often noted that the surrealist movement in the 1920s originated with poets like Paul Éluard and André Breton, himself a trained psychologist, who drew explicitly from the work of Sigmund Freud, “the private world of the mind,” as the Metropolitan Museum of Art puts it. And yet we certainly see the influence of Freudian poetry in the work of Giorgio de Chirico, Marcel Duchamp, Salvador Dalí, Joan Miró, and Man Ray. We also see it, inexplicably, in the work of Hieronymus Bosch, that 15th century Dutch painter of bizarre works like The Garden of Earthly Delights, a triptych that becomes exponentially more nightmarish as one scans across it from left to right. (Take a virtual tour of the painting here), and from which photographer Lori Pond draws in the astonishing photographs you see here.

How does such a faraway figure as Bosch, whom we know so little about, seem to communicate so closely with our epoch’s artistic movements? The Garden of Earthly Delights, writes Stephen Holden at the New York Times, “outstrips in boldness many of the extreme digital fantasies in Hollywood horror films.” Bosch’s incredibly detailed paintings “feel startlingly contemporary.… Reproductions of his paintings have adorned rock album covers, been parodied on The Simpsons and printed on silk bodices designed by Alexander McQueen.” And he was, in fact, named “Trendiest Apocalyptic Medieval Painter of 2014.”

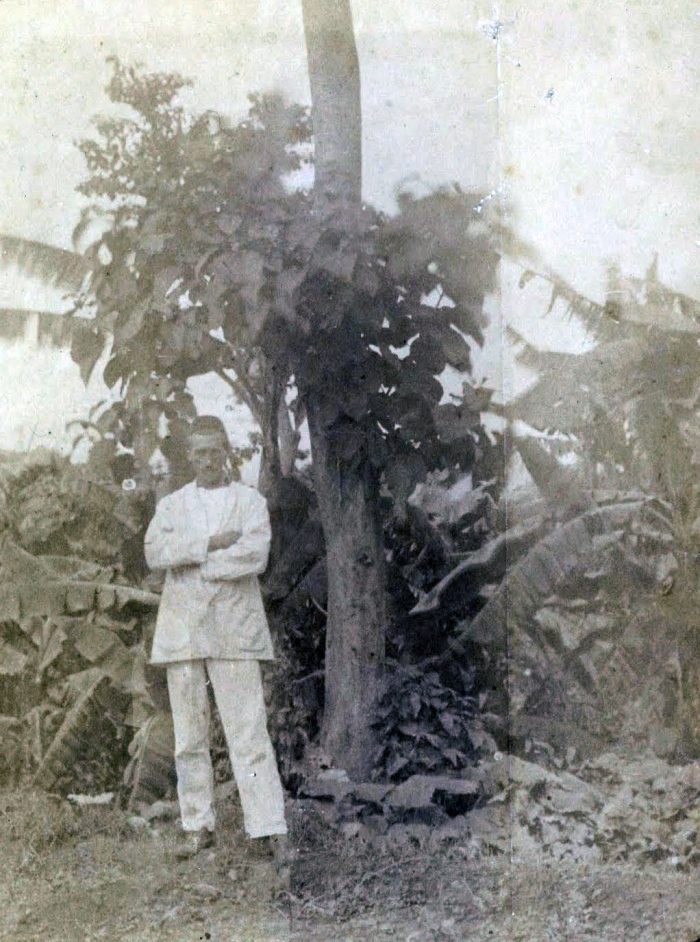

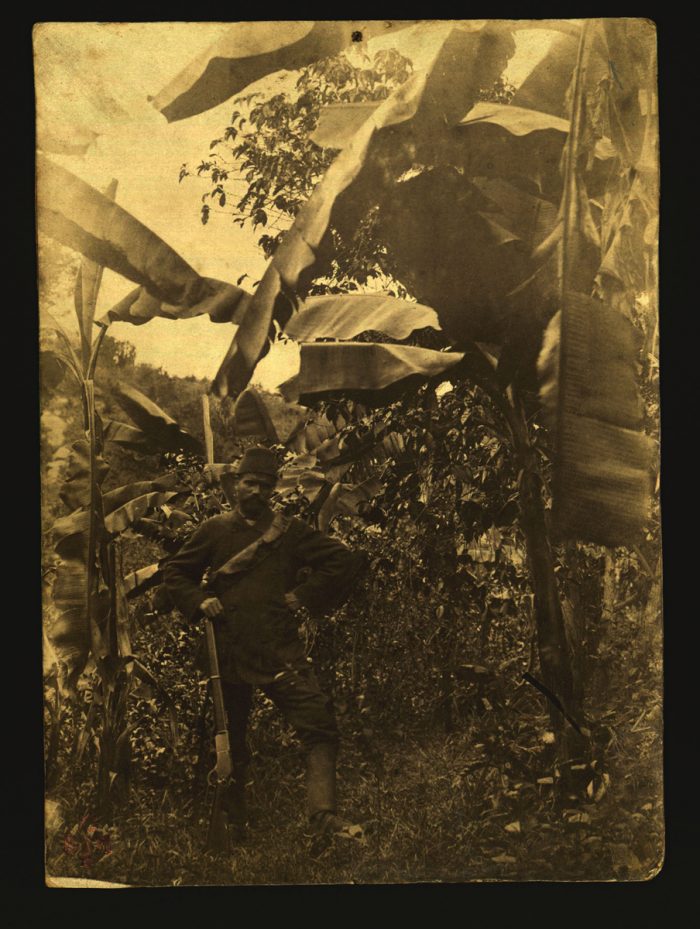

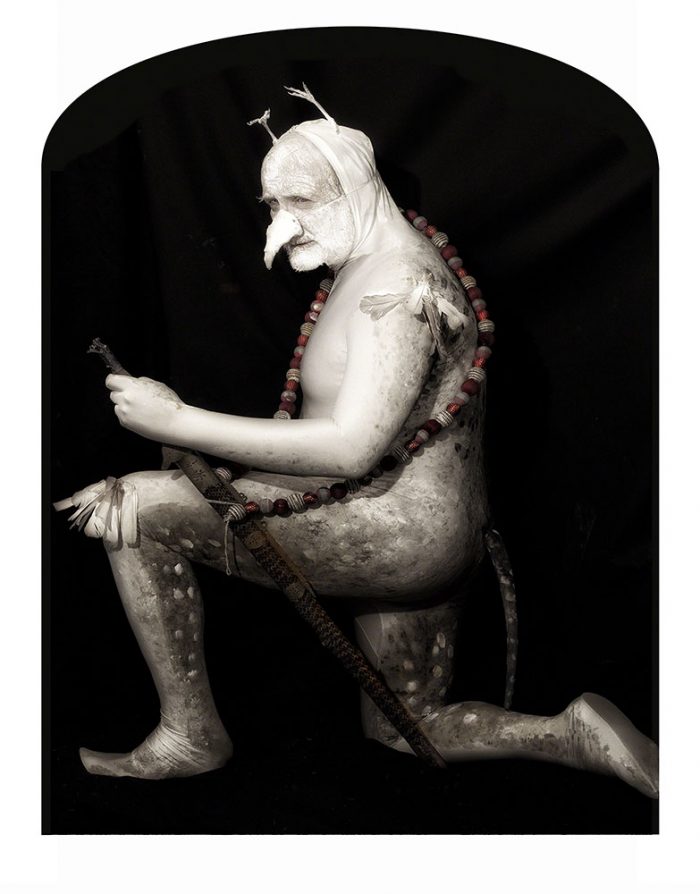

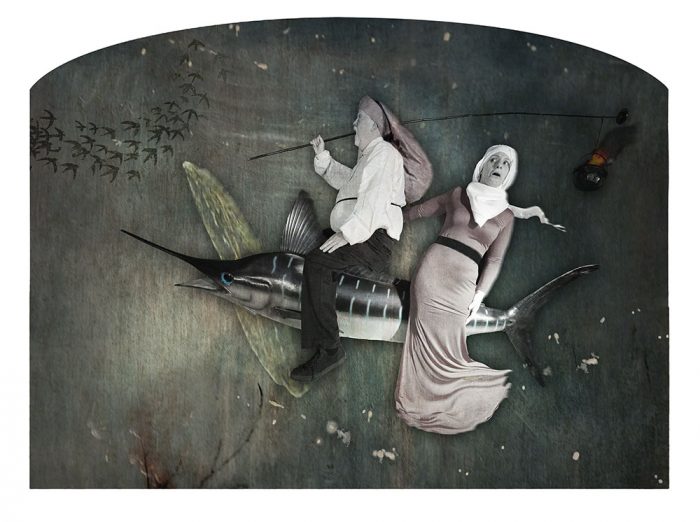

We might well wonder what Bosch would have done with the same technologies as those who now pay him tribute. Perhaps something very much like Pond has with her Bosch Redux series, a collection of photographs of very close-up details in several of Bosch’s paintings, featuring one or two characters. To make these photos, writes Alyssa Coppelman at Adobe’s Create blog, Pond “bought props online, in antique stores, and at swap meets, and friends donated her old Halloween costumes.” She hired a prosthetics designer and her “taxidermy teacher.” For photos like that above from the central panel of the triptych, Pond even hired a set builder to create a life-sized boat that could fit the two real-life models.

Many of these effects might have been accomplished by early twentieth century surrealists, and indeed, when these details from Bosch’s work are amplified they resemble nothing so much as those psychoanalytic modernists. But Pond admits, “I fully abide by the maxim, ‘A photograph isn’t a photograph until it goes through Photoshop.’” She makes the usual adjustments, adds filters and effects, then employs “textures, backgrounds, and other small details from the original paintings,” making Bosch a collaborator in these close-up remixes, which come from The Last Judgment, The Temptation of St. Anthony, and The Garden of Earthly Delights, of course—the painting that first gave her the inspiration when Pond saw it at the Prado in Madrid. You can see many more examples of the series at Pond’s website, sixteen surreally apocalyptic visions in all.

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness