Back in college, I took a survey class on Russian history, taught by one of these people who take up the profession in their active retirement after a career spent working in the field. This particular professor had gone to work for the State Department after graduate school and served in various posts in Soviet Russia for several decades. The format of his class seemed unremarkable on paper. One standard syllabus, one bulky, expensive textbook. But the classes themselves consisted of long, fascinating stories about personal encounters with Brezhnev and Gorbachev, or journeys into ancient Kiev, or to the outer reaches of the Steppes.

All that was missing from those vivid recollections was a comparable photo essay to tell the story visually. This has been remedied and then some by the “The History of Russia,” an enormous joint archive project from Moscow’s Multimedia Art Museum and Yandex, Russia’s largest search engine. The archive contains over 70,000 photos, gathered from “more than 40 institutions and collections,” writes Hyperallergic, and representing “over 150 years of photographs capturing all sorts of scenes of Russian life.”

Non-Russian speakers can load the site in Google Chrome and have it translated into English. Additionally, “a timeline allows you to browse by date, a map enables location-based searches, and preset categories filter the images by theme.” Russian speakers can enter specific keywords into the site’s search engine. Currently, the archive features an exhibition on the August Putsch, the 1991 coup attempt on the presidency of Mikhail Gorbachev, staged by hard-line Communist Party Members opposed to reform. See one iconic photo of that historical event above, and many more at the virtual exhibition.

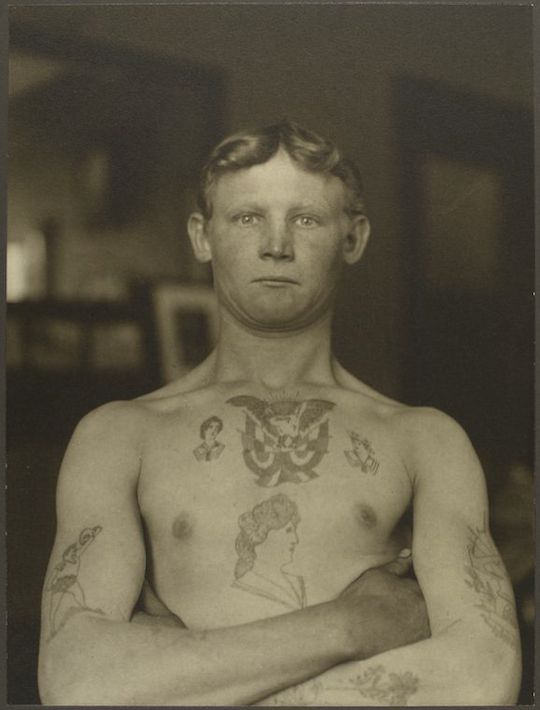

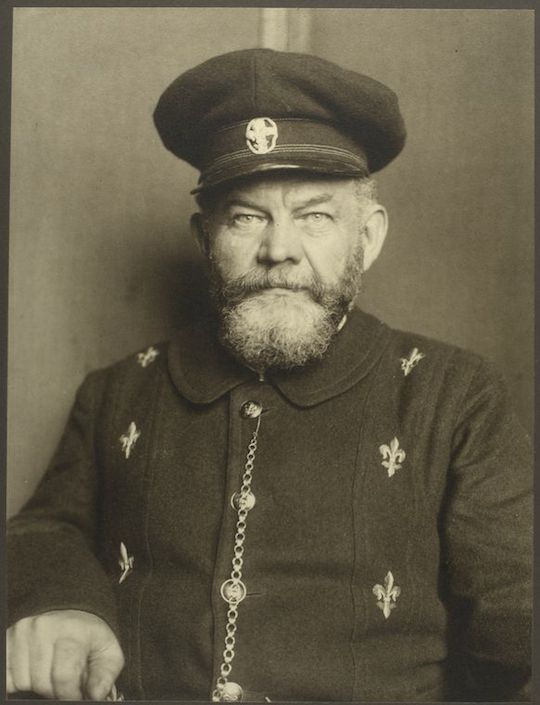

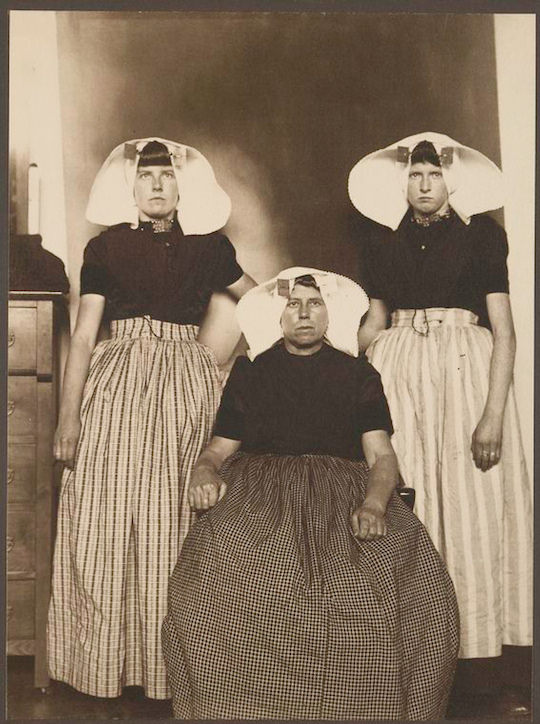

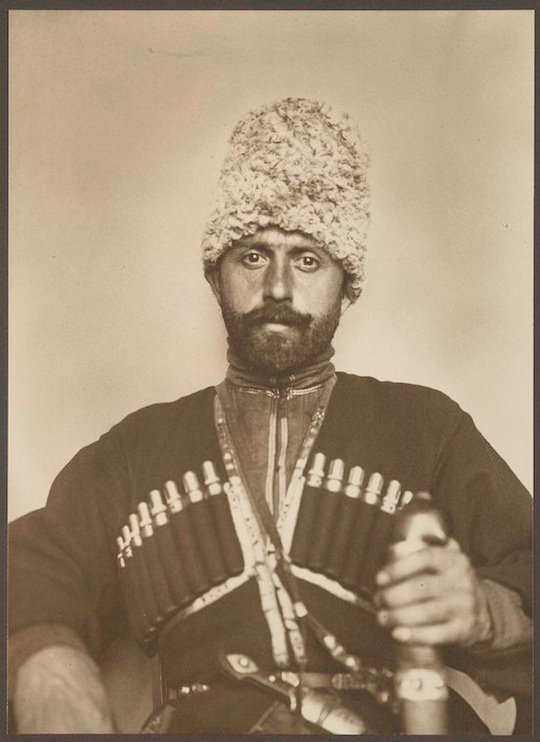

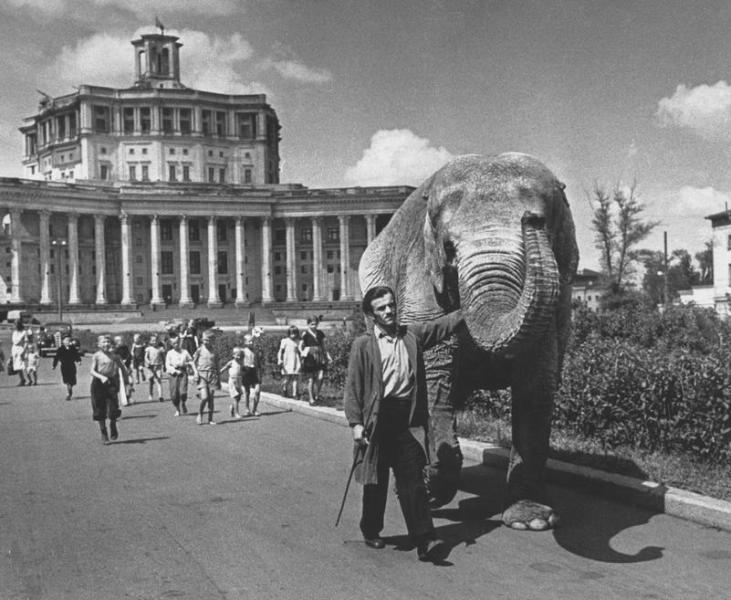

The late 1980s and 90s may be a period of particular interest for students and writers of Russian history, like David Remnick, and for good reason. But every decade in the archive holds its own fascination. Stately portraits from the 1860s, like that at the top of the post, show us the society of Tolstoy in the decade he serialized War and Peace. Photos from the 20s, like the satirical display in Red Square, further down, show us the days of Lenin’s rule and the early years of the Soviet Union. Images from the 50s give us unique insider views—often impossible at the time—of ordinary Soviet life at the height of the Cold War, such as the Christmas tree in the Luzhniki Stadium, above, or the man leading an elephant from the Red Army Theater, below.

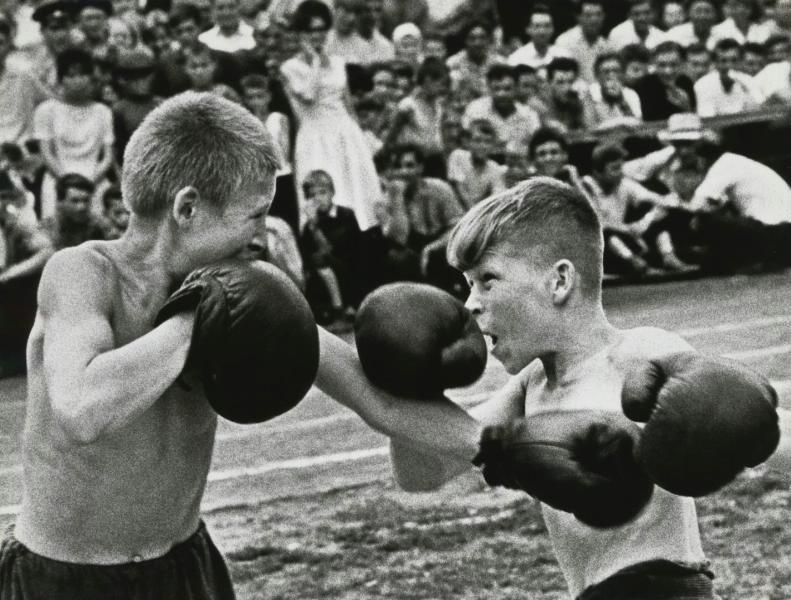

The 60s in particular look like a Life magazine spread, with dramatic photos of Olympic athletes in training, statesmen posed with wives and children, and hundreds of arresting pictures from everyday life, like that of two boys boxing below. The huge galleries can be a little cumbersome to navigate and require some patience on the part of the non-Russian-speaking user. But that patience is richly rewarded with photograph after photograph of a country we rarely hear spoken of in less than inflammatory terms. We encounter, of course, the odd portrait of Stalin and other well-worn propaganda images, but for the most part, the photos look and feel candid, and for good reason.

“According to a release,” Hyperallergic writes, “many of the photographs are published here for the first time, partly because the portal invites users to upload, describe, and tag images from personal archives. It has the feel of a museum collection”—and also of a family photo album stretching back generations. “The History of Russia” archive offers occasional context in addition to the dates, names, and locations of subjects. But informative text appears rarely, and in nearly unreadable translations for us non-speakers. Nonetheless, a few hours lost in these galleries feel like a near total immersion in Russian history. You can enter the archive here.

Related Content:

Download 650 Soviet Book Covers, Many Sporting Wonderful Avant-Garde Designs (1917–1942)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness