If you’re a reader and user of social media, you’ve likely tested your lifetime reading list against the BBC Book Quiz.

Or perhaps you’ve allowed your worth as a reader to be determined by the number of Pulitzer Prize winners you’ve made it through.

The National Endowment for the Arts’ Big Read, anyone?

The 142 Books that Every Student of English Literature Should Read?

The 50 Best Dystopian Novels?

Being young is no excuse! Not when the American Library Association publishes an annual list of Outstanding Books for the College Bound and Lifelong Learners.

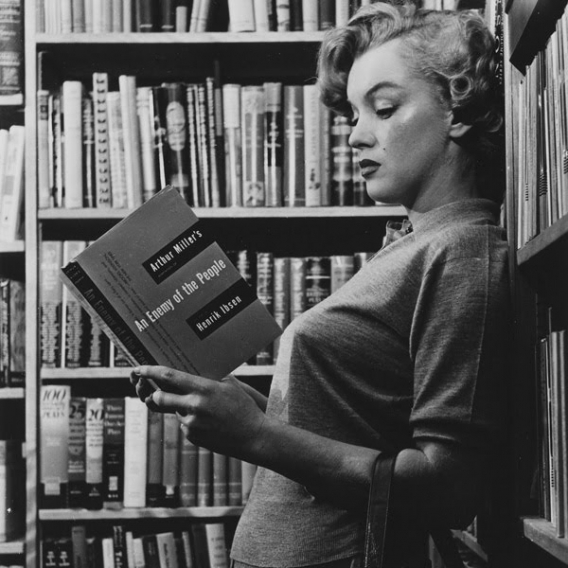

So… how’d you do? Or should I say how’d you do in comparison to Marilyn Monroe? The online Monroe fan club Everlasting Star used photographs, interviews, and a Christie’s auction catalogue to come up with a list of more than 400 books in her possession.

Did she read them all? I don’t know. Have you read every single title on your shelves? (There’s a Japanese word for those books. It’s Tsundoku.)

Feminist biographer Oline Eaton has a great rant on her Finding Jackie blog about the phrase “Marilyn Monroe reading,” and the 5,610,000 search engine results it yields when typed into Google:

There is, within Monroe’s image, a deeply rooted assumption that she was an idiot, a vulnerable and kind and loving and terribly sweet idiot, but an idiot nonetheless. That is the assumption in which ‘Marilyn Monroe reading’ is entangled.

The power of the phrase Marilyn Monroe reading’ lies in its application to Monroe and in our assumption that she wouldn’t know how.

Would that everyone searching that phrase did so in the belief that her passion for the printed word rivaled their own. Imagine legions of geeks loving her for her brain, bypassing Sam Shaw’s iconic subway grate photo in favor of home printed pin ups depicting her with book in hand.

Commemorative postage stamps are nice, but perhaps a more fitting tribute would be an ALA poster. Like Eaton, when I look at that image of Marilyn hunched over James Joyce’s Ulysses (or kicking back reading Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass), I don’t see someone trying to pass herself off as something she’s not. I see a high school dropout caught in the act of educating herself. If I saw it taped to a library shelf emblazoned with the word “READ,” I might just summon the resolve to take a stab at Ulysses myself. (I know how it ends, but that’s about it.)

See below, dear readers. Apologies that we’re not set up to keep track of your score for you, but please let us know in the comments section if you’d heartily second any of Marilyn’s titles, particularly those that are lesser known or have faded from the public view.

Marilyn Monroe’s Reading Challenge

(Thanks to Book Tryst for compiling Everlasting Star’s findings)

1) Let’s Make Love by Matthew Andrews (novelization of the movie)

2) How To Travel Incognito by Ludwig Bemelmans

3) To The One I Love Best by Ludwig Bemelmans

4) Thurber Country by James Thurber

5) The Fall by Albert Camus

6) Marilyn Monroe by George Carpozi

7) Camille by Alexander Dumas

8) Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison

9) The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book by Fannie Merritt-Farmer

10) The Great Gatsby by F Scott Fitzgerald

11) From Russia With Love by Ian Fleming

12) The Art Of Loving by Erich Fromm

13) The Prophet by Kahlil Gilbran

14) Ulysses by James Joyce

15) Stoned Like A Statue: A Complete Survey Of Drinking Cliches, Primitive, Classical & Modern by Howard Kandel & Don Safran, with an intro by Dean Martin (a man who knew how to drink!)

16) The Last Temptation Of Christ by Nikos Kazantzakis

17) On The Road by Jack Kerouac

18) Selected Poems by DH Lawrence

19 and 20) Sons And Lovers by DH Lawrence (2 editions)

21) The Portable DH Lawrence (more…)

MP3

MP3