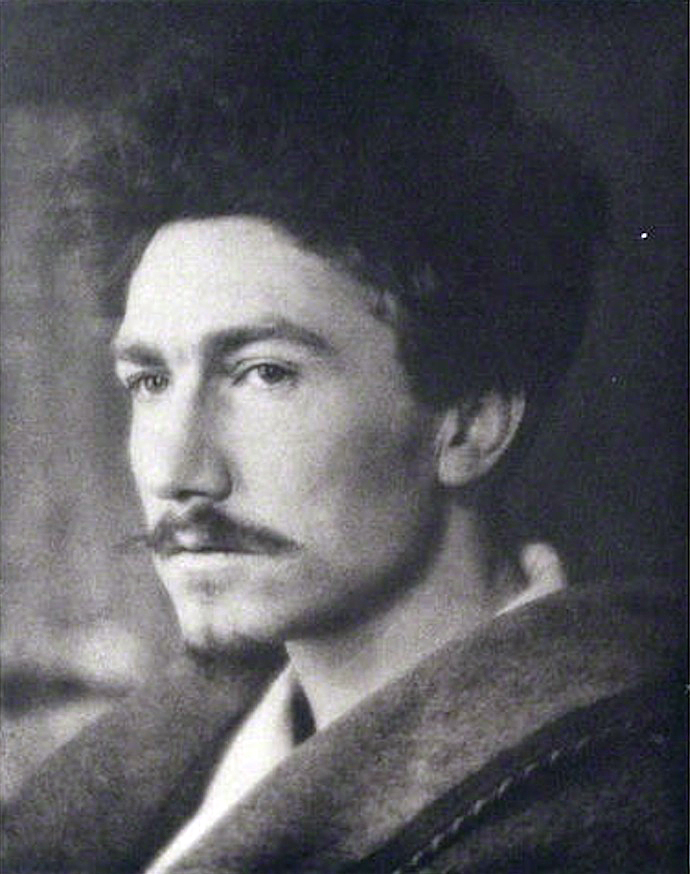

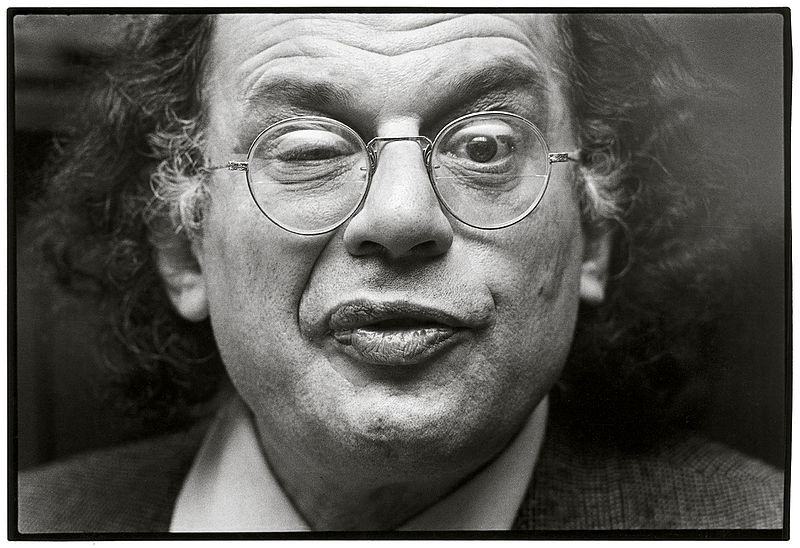

Image by Michiel Hendryckx, via Wikimedia Commons

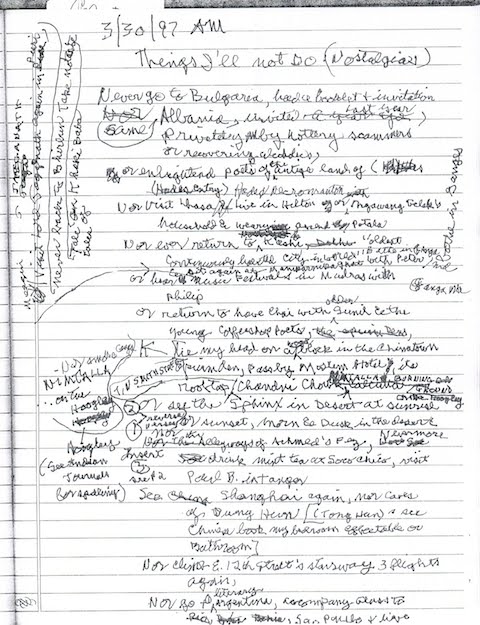

Ginsberg Class One

Ginsberg Class Two

Like so many great poets, Allen Ginsberg composed extemporaneously as he spoke, in erudite paragraphs, reciting lines and whole poems from memory—in his case, usually the poems of William Blake. In a 1966 Paris Review interview, for example, he discusses and quotes Blake at length, concluding “The thing I understood from Blake was that it was possible to transmit a message through time that could reach the enlightened.” Eight years later, Ginsberg would begin to midwife this concept as a teacher at the newly-founded Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics at the Naropa Institute in Boulder, Colorado. Ginsberg taught summer workshops at the school from 1974 until the end of his life, eventually spending the remainder of the year in a full-time position at Brooklyn College. The Internet Archive hosts recordings of many of these workshops, such as his lectures on 19th Century Poetry, Jack Kerouac, Spiritual Poetics, and Basic Poetics. In the audio lectures here, from August 1980, Ginsberg teaches a four-part course on Shakespeare’s The Tempest (parts one and two above, three and four below), a play he often returned to for reference in his own work.

Ginsberg Class Three

Ginsberg Class Four

Ginsberg’s method of teaching Shakespeare is unlike anyone else’s. He’s not interested in exegesis so much as an open conversation—with the text, with his students, and with any ephemera that strikes his interest. It’s almost a kind of divination by which Ginsberg teases out the “messages” Shakespeare’s play sends through the ages, working with the rhythmic and syntactical oddities of individual lines instead of grand, abstract interpretative frameworks. Ginsberg’s pedagogy requires patience on the part of his students. He doesn’t drive toward a point as much as arrive at it circuitously as by the chance operations of his meditative mind. His first of four lectures above, for example, begins with a great deal of futzing around about different editions, which can seem a little tedious to an impatient listener. Give in to the urge to fast-forward, though, and you’ll miss the diamond-like bits of wisdom that emerge from Ginsberg’s discursive exploration of minutiae.

Ginsberg explains to his class why he thinks the Penguin G.B. Harrison edition was the best available at the time because it draws from the original folio and has “more respect than the actual arrangement of the lines for speaking as determined by the editions printed in Shakespeare’s day.” Harrison’s text, he says, recovers the idiosyncrasies of Shakespeare’s lines: “Since [Alexander] Pope and [John] Dryden and others messed with Shakespeare’s texts—straightened them out and modernized them and improved them—they’ve always been reproduced too smoothly.” Such was the hubris of Pope and Dryden. Ginsberg spends a few minutes “correcting” the punctuation of a line for students with more modernized editions. One can see the appeal of the first folio for Ginsberg as he insists that its text is “not all exactly properly lined up pentametric blank verse but is more broken, more irregular lines, more like free verse actually, because it fitted exactly to speech.” Much like his own work in fact, and that of his fellow Beats, whom he reads and draws into the discussion of The Tempest’s poetics throughout the course of his lectures. The Allen Ginsberg Project has more on the poet’s teaching of Shakespeare during his Naropa days.

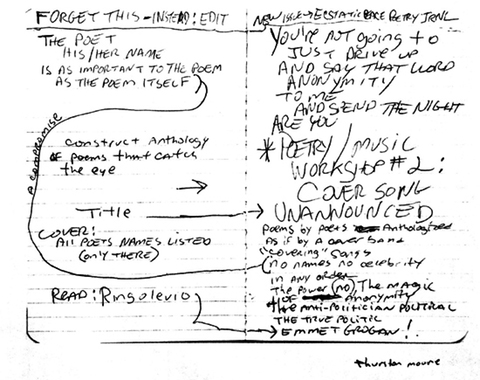

When Ginsberg founded the Jack Kerouac School with Anne Waldman in 1974, he and his fellow Beats had not taught before. They simply invented their own ways of passing on their poetic enlightenment. Invited to create the school at Naropa University in Boulder by his spiritual teacher and Naropa founder Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, Ginsberg seemed to combine in equal parts the Buddhist tradition of spiritual lineage with that of Western literary filiation. He distilled this synthesis in his elliptical 1992 text “Mind Writing Slogans,”: “two decades’ experience teaching poetics at Naropa Institute” and a “half decade at Brooklyn College,” Ginsberg writes, “boiled down to brief mottoes from many sources found useful to guide myself and others in the experience of ‘writing the mind.’” This document is an excellent source of Ginsberg’s eclectic wisdom, as is his “Celestial Homework” reading list for his class “Literary History of the Beats.”

Ginsberg and company’s relationship to Trungpa’s Shambhala Buddhist school, and to the artistic community of Boulder, was not without its detractors. Poet Kenneth Rexroth and others accused Ginsberg and his teacher of a kind of cultic exploitation of Buddhist teachings, of “Buddhist fascism.” The conflict between Ginsberg’s guru and poets like W.S. Merwin—who apparently had a humiliating experience at Naropa—is documented in Tom Clark’s polemical The Great Naropa Poetry Wars. Others remember the Naropa founder much more fondly. Two documentaries offer different portraits of life at Naropa. The first, Fried Shoes, Cooked Diamonds (above)—filmed in 1978 and narrated by Ginsberg himself—presents a raw, in-the-moment picture of the anarchic Kerouac School’s early days. Former Naropa student Kate Lindhardt’s “micro-budget” Crazy Wisdom, below, offers a more detached look at the school and asks questions about what she calls the “institutionalization” of creativity from a more feminist perspective.

Ginsberg’s Tempest course will be added to our collection of 875 Free Online Courses; the films mentioned above can be found in our collection of 640 Free Movies Online. The Tempest and poems by Ginsberg can be found in our collection of Free eBooks.

Related Content:

Allen Ginsberg Recordings Brought to the Digital Age. Listen to Eight Full Tracks for Free

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness