?si=yeo1Xsu2ZLuCpQbC

Most scientists are prepared to answer questions about their research from other members of their field; rather fewer have equipped themselves to answer questions from the general public about what Douglas Adams called life, the universe, and everything. Carl Sagan was one of that minority, an expert “science communicator” before science communication was recognized as a field unto itself. In popular books and television productions, most notably Cosmos and its accompanying series Cosmos: A Personal Voyage, he put himself out there in the mass media as an enthusiastic guide to all that was known about the realms beyond our planet. More than a few members of his audience might well have asked themselves where does God fit into all this.

One such person actually put that question to Sagan, at a Q&A session after the latter’s 1994 “lost lecture” at Cornell, titled “The Age of Exploration.” The questioner, a graduate student, asks, “Is there any type of God to you? Like, is there a purpose, given that we’re just sitting on this speck in the middle of this sea of stars?”

In response to this difficult line of inquiry, Sagan opens a more difficult one: “What do you mean when you use the word God?” The student takes another tack, asking, “Given all these demotions” — defined by Sagan himself as the continual humbling of humanity’s self-image in light of new scientific discoveries — “why don’t we just blow ourselves up?” Sagan comes back with yet another question: “If we do blow ourselves up, does that disprove the existence of God?” The student admits that he guesses it does not.

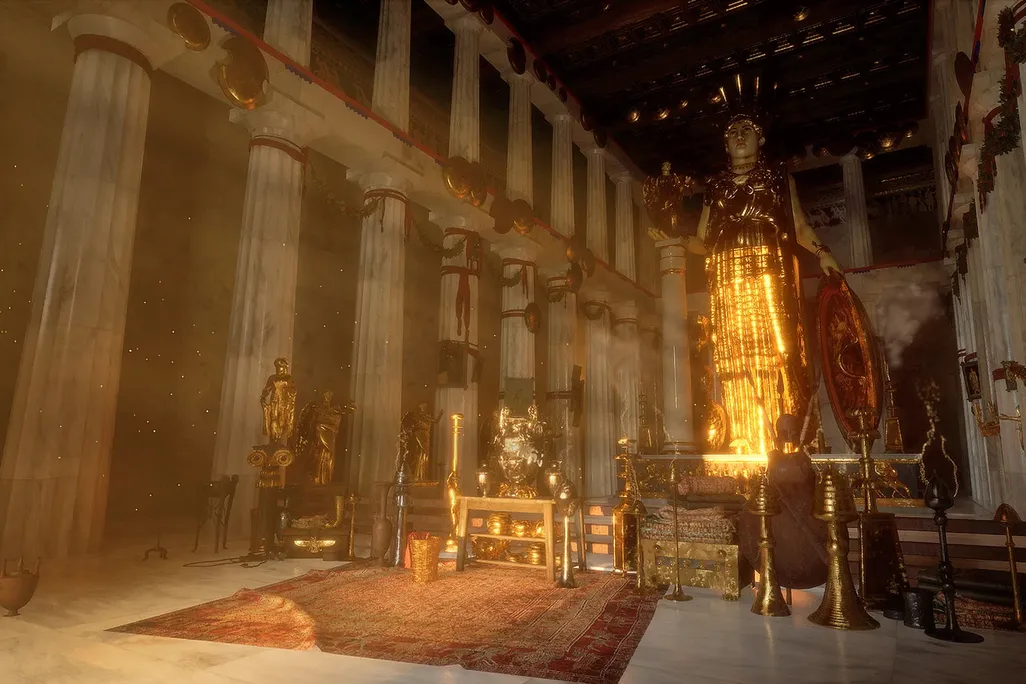

The question eventually gets Sagan considering how “the word ‘God’ covers an enormous range of different ideas.” That range “runs from an outsized, light-skinned male with a long white beard, sitting in a throne in the sky, busily tallying the fall of every sparrow,” for whose existence Sagan knows of no evidence, to “the kind of God that Einstein or Spinoza talked about, which is very close to the sum total of the laws of the universe,” and as such, whose existence even Sagan would have to acknowledge. There’s also “the deist God that many of the founding fathers of this country believed in,” who’s held to have created the universe and then removed himself from the scene. With such a broad range of possible definitions, the concept of God itself becomes useless except as “social lubrication,” a means of seeming to “agree with someone else with whom you do not agree.” Terms of that malleable kind do have their advantages, if not to the scientific mind.

Related content:

Carl Sagan, Stephen Hawking & Arthur C. Clarke Discuss God, the Universe, and Everything Else

150 Renowned Secular Academics & 20 Christian Thinkers Talking About the Existence of God

Bertrand Russell on the Existence of God & the Afterlife (1959)

Bertrand Russell and F.C. Copleston Debate the Existence of God, 1948

What Is Religion Actually For?: Isaac Asimov and Ray Bradbury Weigh In

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.