The Lord said to Noah, there’s going to be a floody, floody; then to get those children out of the muddy, muddy; then to build him an arky, arky. This much we heard while toasting marshmallows around the campfire, at least if we grew up in a certain modern Protestant tradition. As adults, we may or may not believe that there ever lived a man called Noah who built an ark to save all the world’s innocent animal species from a sin-cleansing flood. But unless we’ve taken a deep dive into ancient history, we probably don’t know that this especially famous Bible story wasn’t the first of its particular subgenre. As explained in the Hochelaga video above, there are even older global-deluge tales to be reckoned with.

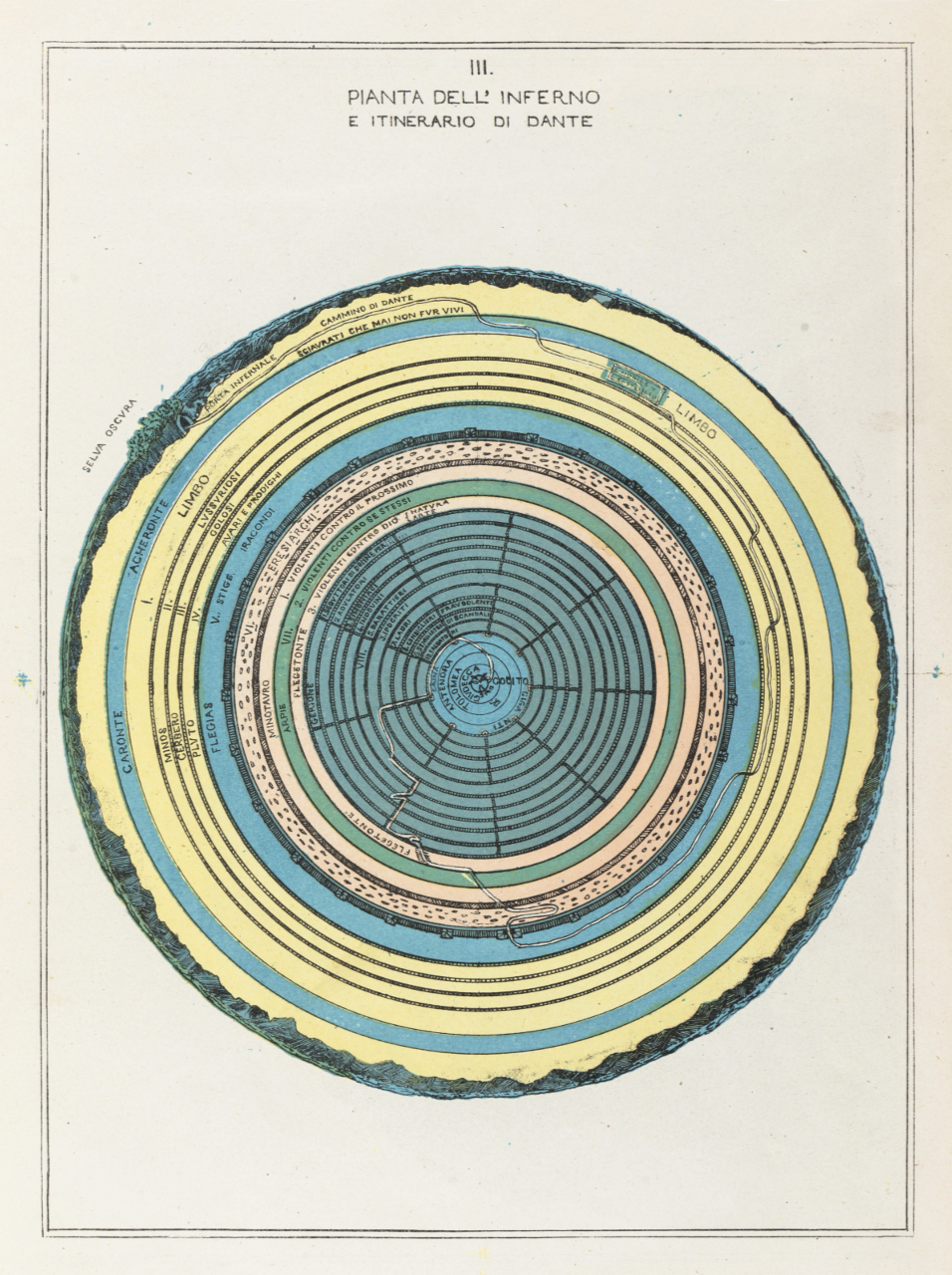

In fact, one such myth appears in the oldest known work of literature in human history, the Epic of Gilgamesh. “In it, the god Ea learns of this divine flood, and secretly warns the humans about this coming disaster,” says Hochelaga creator Tommie Trelawny. Thus informed, the king Utnapishtim builds a giant coracle, a kind of circular boat “used to navigate the rivers of Mesopotamia for centuries.”

Like Noah, Utnapishtim brings his family and a host of animals aboard, and after riding out the worst of the storm, finds that his craft has come to rest on a mountaintop. Also like Noah, he then sends birds out to find dry land. But ultimately, “the story takes a strange turn: instead of being pleased, the gods are angry,” though Ea does step in to take responsibility and make sure that Utnapishtim is rewarded.

There are other versions with other gods, floods, and ark-builders as well. In the Religion for Breakfast video just above, religious studies scholar Andrew Mark Henry compares the Biblical story of Noah and the Utnapishtim episode of the Epic of Gilgamesh with the “Sumerian flood story” from the second millennium BC and the two-centuries-older “Atrahasis epic.” All of these versions have a good deal in common, not least the executive decision by an exasperated higher being (or beings) to wipe out almost entirely the humanity they themselves created. Ironically, we moderns are likely to have first encountered this tale of godly wrath and subsequent mass destruction in lighthearted, even cheerful presentations. Whether ancient Sumerians also sang about it in youth groups, no clay tablet has yet revealed.

Related content:

A Map of All the Countries Mentioned in the Bible: What The Countries Were Called Then, and Now

Did the Tower of Babel Actually Exist?: A Look at the Archaeological Evidence

The Epic of Gilgamesh, the Oldest-Known Work of Literature in World History

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.