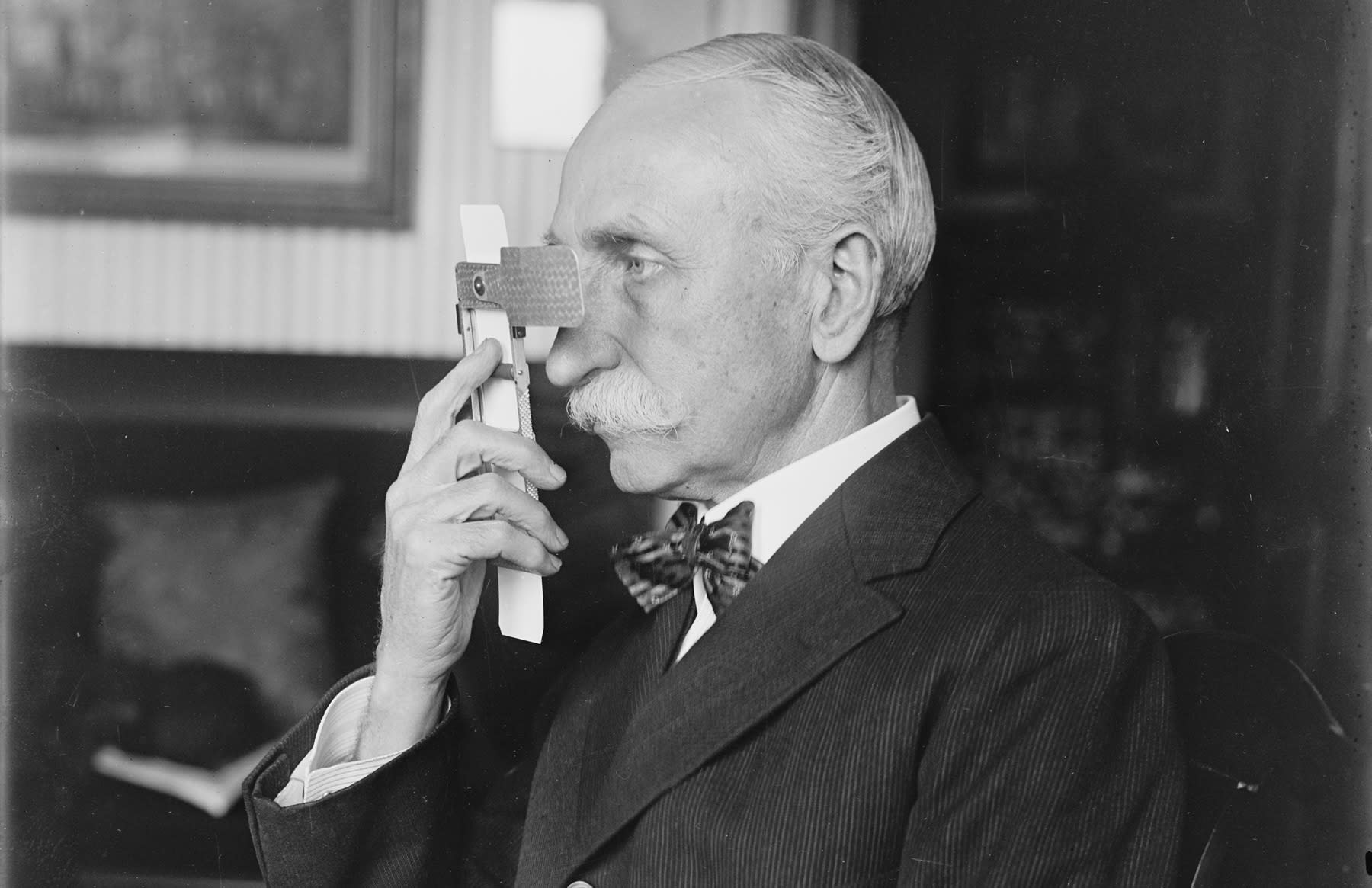

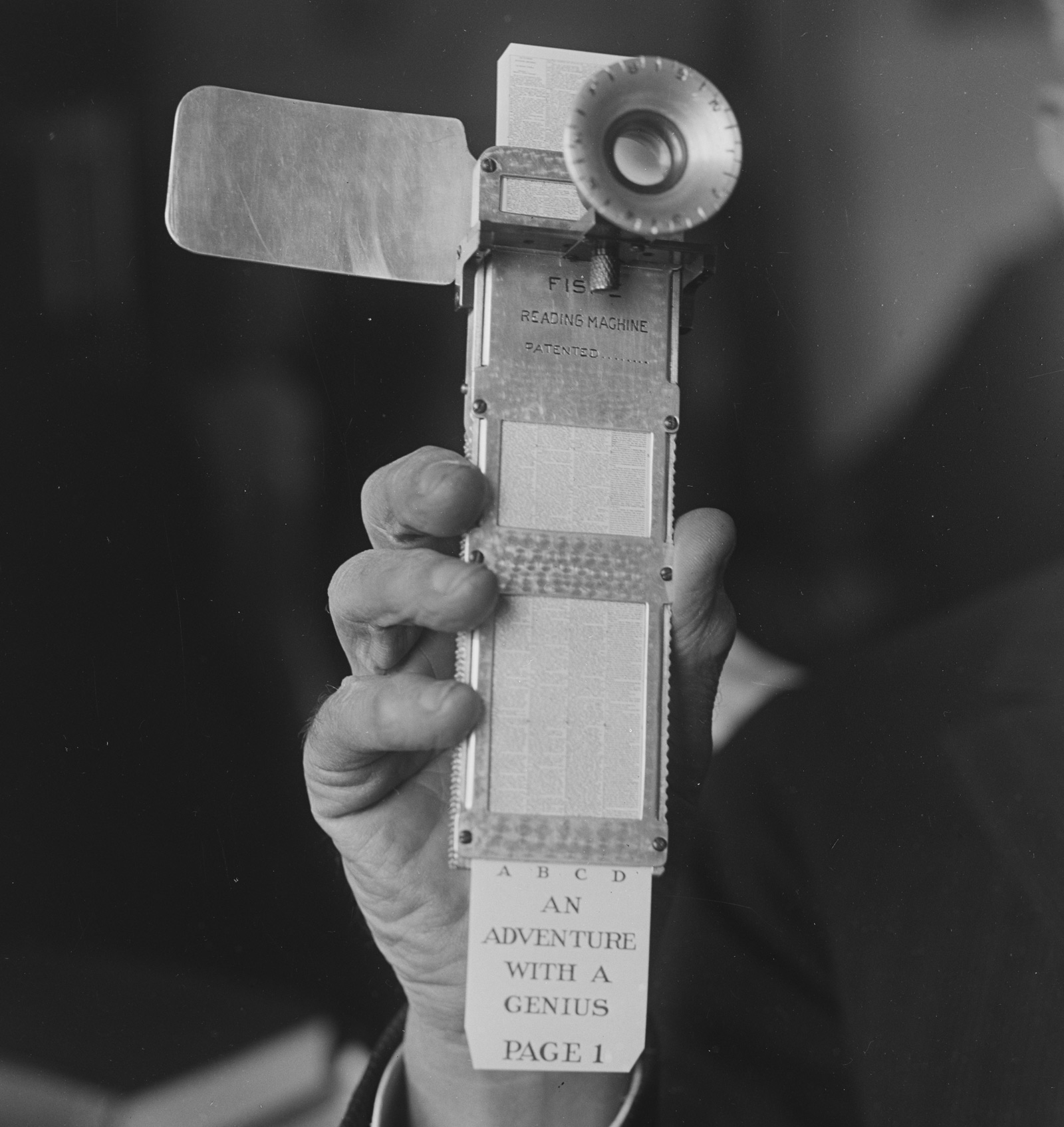

The first compact discs and players came out in October of 1982. That means the format is now 40 years old, which in turn means that most avid music-listeners have never known a world without it. In fact, all of today’s teenagers — that most musically avid demographic — were born after the CD’s commercial peak in 2002, and to them, no physical medium could be more passé. Vinyl records have been enjoying a long twenty-first-century resurgence as a premium product, and even cassette tapes exude a retro appeal. But how many understand just what a technological marvel the CD was when it made its debut, with (what we remember as) its promise of “perfect sound forever”?

“You could argue that the CD, with its vast data capacity, relatively robust nature, and with the further developments it spurred along, changed how the world did virtually all media.” So says Alec Watson, host of the Youtube channel Technology Connections, previously featured here on Open Culture for his five-part series on RCA’s SelectaVision video disc system.

But he’s also made a six-part miniseries on the considerably more successful compact disc, whose development “solved the central problem of digital sound: needing a for-the-time-absurdly massive amount of raw data.” Back then, computer hard drives had a capacity of about ten megabytes, whereas a single disc could hold up to 700 megabytes.

Figuring out how to encode that much information onto a thin 120-millimeter disc required serious resources and engineering prowess (available thanks to the involvement of two electronics giants, Sony and Philips), but it constituted only one of the technological elements needed for the CD to become a viable format. Watson covers them all in this miniseries, beginning with the invention of digital sound itself (including the Nyquist-Shannon sampling theorem on which it depends). He also explains such physical processes as how a CD player’s laser reads the “pits” and “lands” on a disc’s surface, producing a stream of numbers subsequently converted back into an audio signal for our listening pleasure.

The CD has also changed our relationship to that pleasure. “If CDs marked a new era, it is perhaps as much in the way they suggest specific ways of interacting with recorded music as in questions of fidelity,” writes The Quietus’ Daryl Worthington. “The fact CDs can be programmed, and tracks easily skipped, is perhaps their most significant feature when it comes to their legacy. They loosened up the album as a fixed document.” Paradoxically, “they’re also the format par excellence for the album as a comprehensive, self-contained unit to be played from start to finish.” Even if you can’t remember when last you put one on, fourteen million of them were sold last year, as against five million vinyl LPs and 200,000 cassettes. At 40, the CD may no longer feel like a miraculous technology, but we can hardly count it out just yet.

Related content:

The Story of How Beethoven Helped Make It So That CDs Could Play 74 Minutes of Music

The Story of the MiniDisc, Sony’s 1990s Audio Format That’s Gone But Not Forgotten

How Vinyl Records Are Made: A Primer from 1956

A Celebration of Retro Media: Vinyl, Cassettes, VHS, and Polaroid Too

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.