Despite having recently begun to admit tour groups, Japan remains inaccessible to most of the world’s travelers. Having closed its gates during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the country has shown little inclination to open them up again too quickly or widely. The longer this remains the case, of course, the more intense everyone’s desire to visit Japan becomes. Though different travelers have different interests to pursue in the Land of the Rising sun — temples and shrines, trains and cafés, anime and manga — all of them are surely united by one appreciation in particular: that of Japanese food.

Wherever in the world we happen to live, most of us have a decent Japanese restaurant or two in our vicinity. Alas, as anyone with experience in Japan has felt, the experience of eating its cuisine anywhere else doesn’t quite measure up; a ramen meal can taste good in a California strip mall, not the same as it would taste in a Tokyo subway station.

At least the twenty-first century affords us one convenient means of enjoying audiovisual evocations of genuine Japanese eateries: Youtube videos. The channel Japanese Noodles Udon Soba Kyoto Hyōgo, for instance, has captivated large audiences simply by showing what goes on in the humble kitchens of western Japan’s Kyoto and Hyōgo prefectures.

Hyōgo contains the coastal city of Kobe as well as Himeji Castle, which dates back to the fourteenth century. The prefecture of Kyoto, and especially the onetime capital of Japan within it, needs no introduction, such is its worldwide renown as a site of cultural and historical richness. Right up until the pandemic, many were the foreigners who journeyed to Kyoto in search of the “real Japan.” Whether such a thing truly exists remains an open question, but if it does, I would locate it — in Kyoto, Hyōgo, or any other region of the country — in the modest restaurants of its back alleys and shotengai market complexes, the ones that have been serving up bowls of noodles and plates of curry for decade upon decade.

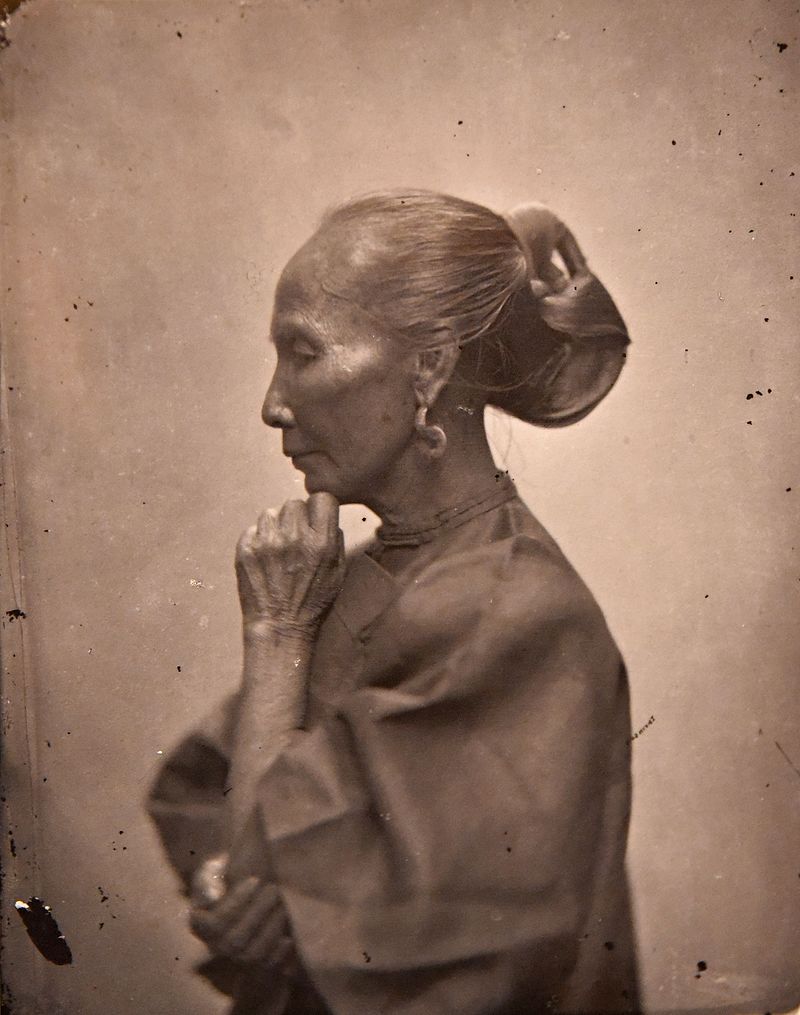

Ideally the décor never changes at these establishments, nor do the proprietors. The video at the top of the post visits a “good old diner” in Kobe to show the skills of a “hard working old lady” with the status of a “veteran cook chosen by God.” In another such neighborhood restaurant, located near the main train station in the city of Amagasaki, a “super mom” prepares her signature udon noodles. But even she looks like a newcomer compared to the lady who’s been making udon over in Kyoto for 58 years at a diner in existence for a century. Soba, tonkatsu, oyakodon, tempura, okonomiyaki: whichever Japanese dish you’ve been craving for the past couple of years, you can watch a video on its preparation — and make your long-term travel plans accordingly.

Related content:

How to Make Sushi: Free Video Lessons from a Master Sushi Chef

Cookpad, the Largest Recipe Site in Japan, Launches New Site in English

How Soy Sauce Has Been Made in Japan for Over 220 Years: An Inside View

The Proper Way to Eat Ramen: A Meditation from the Classic Japanese Comedy Tampopo (1985)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.