If you’ve ever been to Japan, you’ll know that in Japanese restaurants, mistakes are not made. And on the off chance that a mistake is made, even a trivial one, the lengths that proprietors will go to make things right with their customers must, in the eyes of a Westerner, be seen to be believed. But as its name suggests, the Tokyo pop-up Restaurant of Mistaken Orders does things a bit differently. “You might think it’s crazy. A restaurant that can’t even get your order right,” says its English introduction page. “All of our servers are people living with dementia. They may, or may not, get your order right.”

Un-Japanese though that concept may seem at first, it actually reflects realities of Japanese society in the 21st century: Japan has an aging population with an already high proportion of elderly people, and that puts it on track to have the fastest growing number of prevalent cases of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Whole towns have already begun to structure their services around a growing number of citizens with dementia. But dementia itself remains “widely misunderstood,” says Restaurant of Mistaken Orders producer Shiro Oguni in the “concept movie” at the top of the post. “People believe you can’t do anything for yourself, and the condition will often mean isolation from society. We want to change society to become more easy-going so, dementia or no dementia, we can live together in harmony.”

You can see more of the Restaurant of Mistaken Orders in last year’s “report movie” just above, which shows its team of servers with dementia in action. Some shown are in middle age, some are in their tenth decade of life, but all seem to have a knack for building rapport with their customers — a skill that anyone who has ever worked front-of-the-house in a restaurant will agree is essential, especially when mistakes happen. We see them deliver orders both correct and incorrect, but the diners seem to enjoy the experience either way: “37% of our orders were mistaken,” the restaurant reports, “but 99% of our customers said they were happy.” This contains another truth about Japanese food culture that anyone who has eaten in Japan will acknowledge: whatever you order, the chance of its being delicious is approximately 100%.

Related Content;

In Touching Video, People with Alzheimer’s Tell Us Which Memories They Never Want to Forget

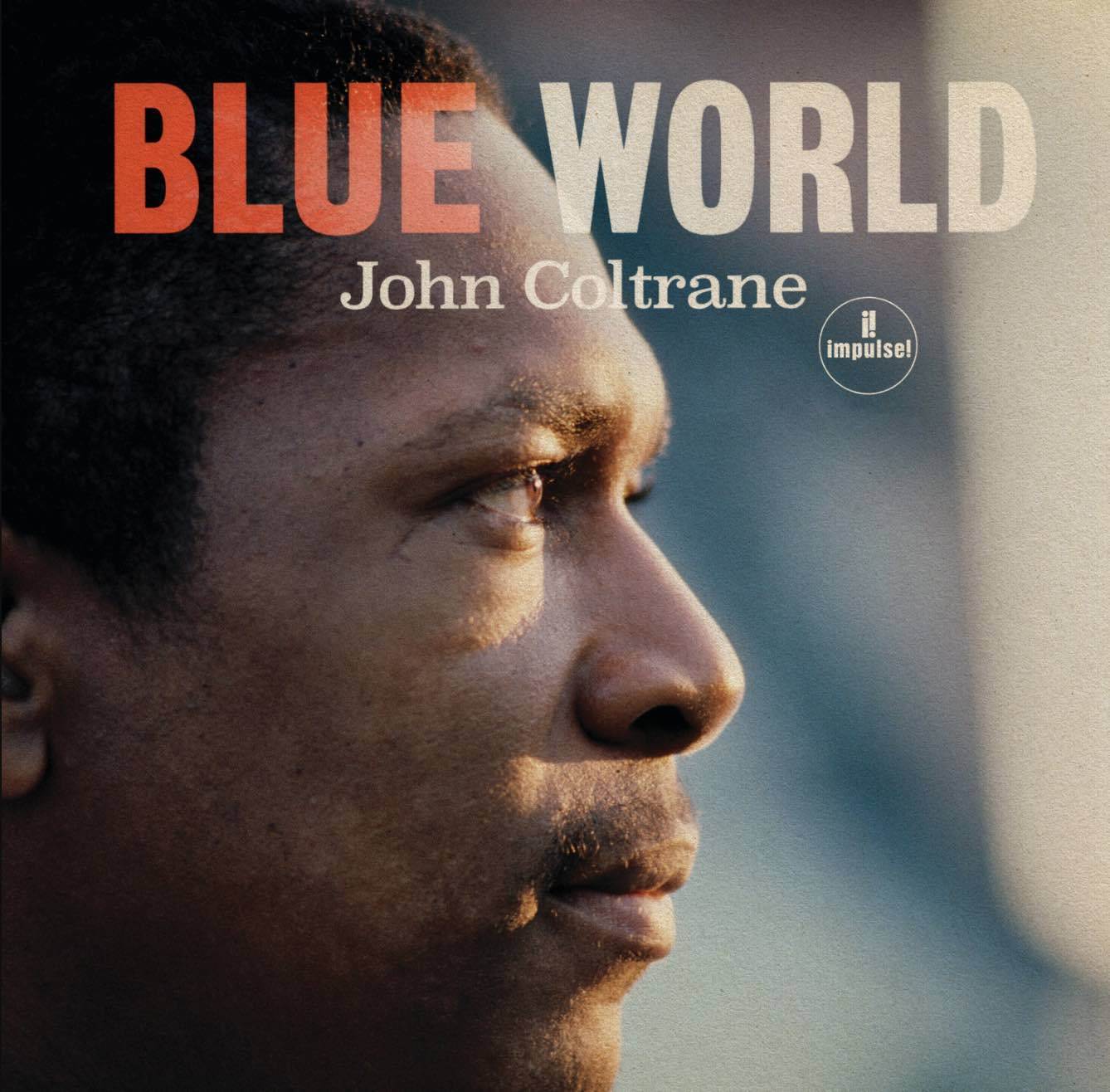

How Music Can Awaken Patients with Alzheimer’s and Dementia

Dementia Patients Find Some Eternal Youth in the Sounds of AC/DC

In Japanese Schools, Lunch Is As Much About Learning As It’s About Eating

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.