No matter how long I live, the dehumanizing insanity of racism will never fail to astonish and amaze me. Not only does it visit great physical and psychological violence upon its victims, but it leaves those who embrace it unable to feel or reason properly. Contemporary examples abound in excess, but many of the most egregious come from the period in U.S. history when an entire class of people was deemed property, and allowed to be treated any way their owners liked. In such a situation, oddly, many slave masters thought of themselves as humane and benevolent, and thought their slaves well-treated, though they would never have traded places with them for anything.

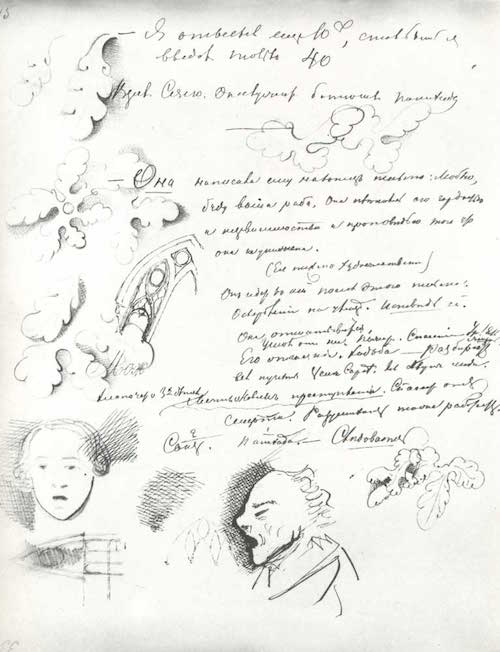

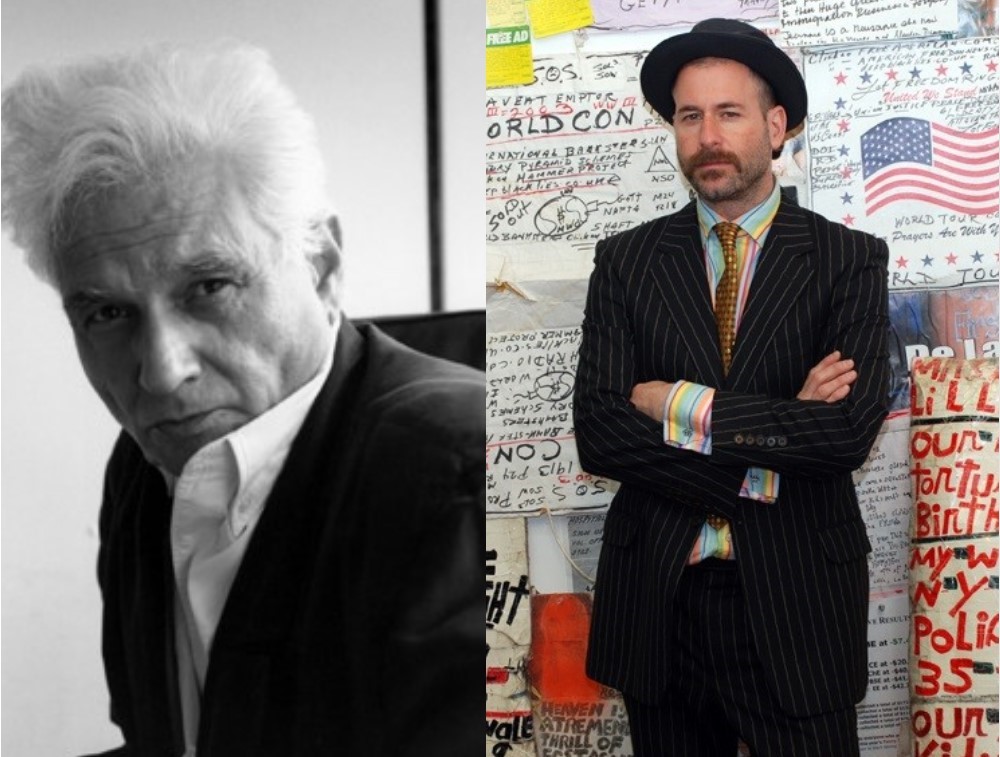

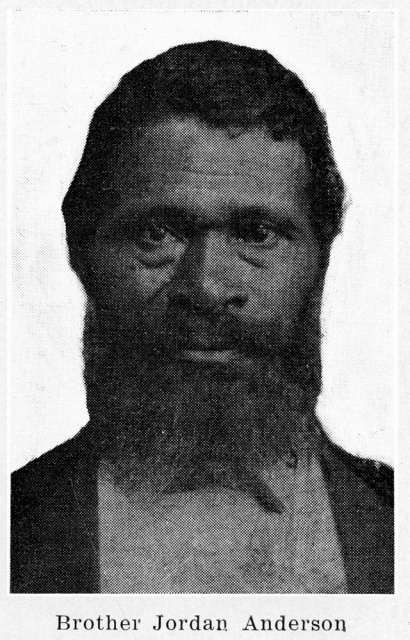

One such example of this bewildering logic comes from a letter written—or dictated, rather—by a man named Jordan Anderson (or sometimes Jourdan Anderson), pictured above: a man enslaved to one Colonel Patrick Henry Anderson in Big Spring, Tennessee. When he was freed from subjection in 1864, Jordan moved to Ohio, found work—was paid for it—and settled down for the next 40 years to raise his children with his wife Amanda. As Allen G. Breed and Hillel Italie write, “he lived quietly and would likely have been forgotten, if not for a remarkable letter to his former master published in a Cincinnati newspaper shortly after the Civil War.”

As did many former slave owners, Colonel Anderson found that he could not keep up his holdings after losing his captive labor force. Desperate to save his property, he had the temerity to write to Jordan and ask him to return and help bring in the harvest. We do not, it seems, have the Colonel’s letter, but we can surmise from Jordan’s response what it contained—promises, as the former slave writes, “to do better for me than anybody else can.” We can also surmise, given Jordan’s sardonic references, that the former master may have shot at him—and that someone named “Henry” intended to shoot him still. We can surmise that the Colonel’s sons may have raped Jordan’s daughters, Matilda and Catherine, given the harrowing description of them “brought to shame by the violence and wickedness of their young masters.”

And, of course, we know for certain that Jordan received no recompense for his many years of hard work: “there was never any pay-day for the negroes,” he writes, “any more than for the horses and cows.” Despite all this—and it is beyond my comprehension why—Colonel Anderson expected that his former slave would return to help prop up the failing plantation. On this score, Jordan proposes a test of the Colonel’s “sincerity.” Tallying up all the wages he and his wife were owed for their combined 52 years of work, less “what you paid for our clothing” and doctor’s visits, he presents his former owner with a bill for “eleven thousand six hundred and eighty dollars” and an address to which he can mail the payment. “If you fail to pay us for faithful labors in the past, we can have little faith in your promises in the future,” he writes. You can read the full letter—which appeared at Letters of Note—below.

Dayton, Ohio,

August 7, 1865

To My Old Master, Colonel P.H. Anderson, Big Spring, Tennessee

Sir: I got your letter, and was glad to find that you had not forgotten Jourdon, and that you wanted me to come back and live with you again, promising to do better for me than anybody else can. I have often felt uneasy about you. I thought the Yankees would have hung you long before this, for harboring Rebs they found at your house. I suppose they never heard about your going to Colonel Martin’s to kill the Union soldier that was left by his company in their stable. Although you shot at me twice before I left you, I did not want to hear of your being hurt, and am glad you are still living. It would do me good to go back to the dear old home again, and see Miss Mary and Miss Martha and Allen, Esther, Green, and Lee. Give my love to them all, and tell them I hope we will meet in the better world, if not in this. I would have gone back to see you all when I was working in the Nashville Hospital, but one of the neighbors told me that Henry intended to shoot me if he ever got a chance.

I want to know particularly what the good chance is you propose to give me. I am doing tolerably well here. I get twenty-five dollars a month, with victuals and clothing; have a comfortable home for Mandy,—the folks call her Mrs. Anderson,—and the children—Milly, Jane, and Grundy—go to school and are learning well. The teacher says Grundy has a head for a preacher. They go to Sunday school, and Mandy and me attend church regularly. We are kindly treated. Sometimes we overhear others saying, “Them colored people were slaves” down in Tennessee. The children feel hurt when they hear such remarks; but I tell them it was no disgrace in Tennessee to belong to Colonel Anderson. Many darkeys would have been proud, as I used to be, to call you master. Now if you will write and say what wages you will give me, I will be better able to decide whether it would be to my advantage to move back again.

As to my freedom, which you say I can have, there is nothing to be gained on that score, as I got my free papers in 1864 from the Provost-Marshal-General of the Department of Nashville. Mandy says she would be afraid to go back without some proof that you were disposed to treat us justly and kindly; and we have concluded to test your sincerity by asking you to send us our wages for the time we served you. This will make us forget and forgive old scores, and rely on your justice and friendship in the future. I served you faithfully for thirty-two years, and Mandy twenty years. At twenty-five dollars a month for me, and two dollars a week for Mandy, our earnings would amount to eleven thousand six hundred and eighty dollars. Add to this the interest for the time our wages have been kept back, and deduct what you paid for our clothing, and three doctor’s visits to me, and pulling a tooth for Mandy, and the balance will show what we are in justice entitled to. Please send the money by Adams’s Express, in care of V. Winters, Esq., Dayton, Ohio. If you fail to pay us for faithful labors in the past, we can have little faith in your promises in the future. We trust the good Maker has opened your eyes to the wrongs which you and your fathers have done to me and my fathers, in making us toil for you for generations without recompense. Here I draw my wages every Saturday night; but in Tennessee there was never any pay-day for the negroes any more than for the horses and cows. Surely there will be a day of reckoning for those who defraud the laborer of his hire.

In answering this letter, please state if there would be any safety for my Milly and Jane, who are now grown up, and both good-looking girls. You know how it was with poor Matilda and Catherine. I would rather stay here and starve—and die, if it come to that—than have my girls brought to shame by the violence and wickedness of their young masters. You will also please state if there has been any schools opened for the colored children in your neighborhood. The great desire of my life now is to give my children an education, and have them form virtuous habits.

Say howdy to George Carter, and thank him for taking the pistol from you when you were shooting at me.

From your old servant,

Jourdon Anderson.

Several historians have researched the authenticity of Jordan’s dictated letter and the historical details of his life in Tennessee and Ohio. As Kottke reported, a man named David Galbraith found information about Jordan’s life after the letter’s publication, including references to him and his wife and family in the 1900 Ohio census. Kottke provides many additional details about Jordan’s post-slavery life and that of his many children and grandchildren, and the Daily Mail has photographs of the former Anderson plantation and Jordan Anderson’s modern-day descendants. They also quote historian Raymond Winbush, who tracked down some of the Colonel’s descendants still living in Big Spring.

Colonel Anderson, it seems, was forced to sell the land after his plea to Jordan failed, and he died not long after at age 44. (Jordan Anderson died in 1907 at age 81.) “What’s amazing,” says Winbush, “is that the current living relatives of Colonel Anderson are still angry at Jordan for not coming back.” Yet another example of how the ignominy of the past, no matter how much we’d prefer to forget it, never seems very far behind us at all.

via Letters of Note

Related Content:

Visualizing Slavery: The Map Abraham Lincoln Spent Hours Studying During the Civil War

Watch Veterans of The US Civil War Demonstrate the Dreaded Rebel Yell (1930)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness