The lag time between our imagining of social equality and its arrival can be significantly long indeed, or it least it can seem so, given the limitations of human mortality. 113 years may not be an especially long time for a tree, say, or even a very healthy Galapagos tortoise, but if you or I had been alive in 1902, chances are we’d never know that in 2015 the president of Europe’s most powerful nation is a woman, as are two major presidential candidates in the United States. Given the amount of inequality we still see worldwide, this may not always feel like a triumph. In 1902, it might have seemed like “nothing but fantasy.”

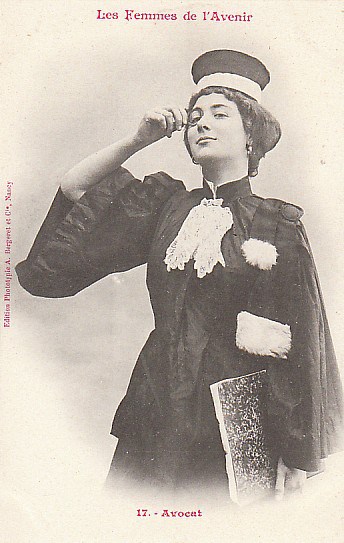

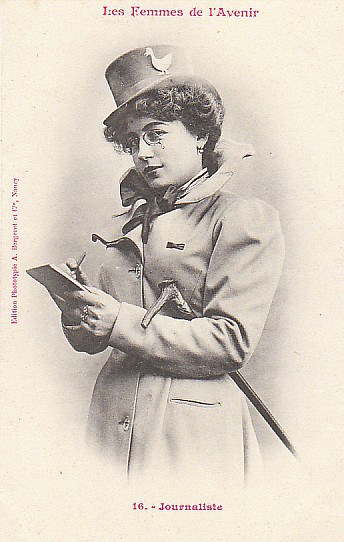

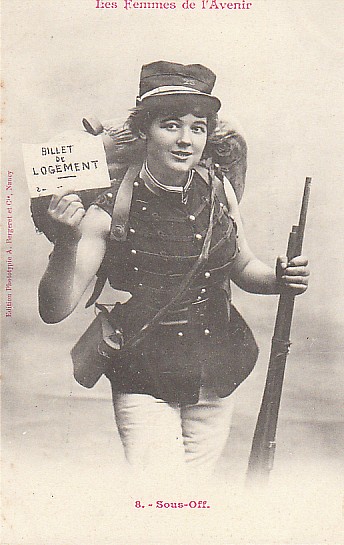

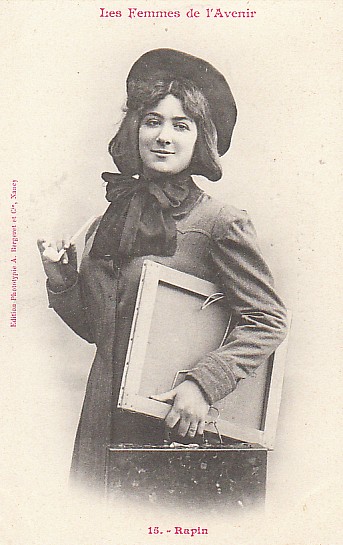

And yet even then, it was certainly possible to foresee women occupying all the roles that men did, through the lenses, writes Laura Hudson at Boing Boing, of “fantasy and science fiction,” which “can often help us open our minds behind the limitations of the world we live in and imagine a better one instead.” In 1902, artist Albert Bergeret was commissioned to create the trading cards you see here—just a small selection of twenty total photographs called “Les Femmes de l’Avenir”—Women of the Future. Only one theme among many in a series of different sets of cards, this “retrofuturistic attempt to expand the role of women in society” showed us a “small and fashionable world” where “women were given a more equal role in society, not to mention spectacular hats.”

That may be so, but just as we can never accurately see the future, we can also never reach consensus on the meaning of the past. The Daily Mail’s Maysa Rawi agrees with Hudson about the “pin-up quality to many of the images,” which show “an awful lot of arm.” And yet Rawi disparages the entire set as “meant to capture men’s fantasies rather than be part of any feminist movement.” I’ll admit, I don’t see the cards this way at all, nor do I think the categories are mutually exclusive. Pin-up girls have also represented social power, albeit mainly sexual power. Scantily-clad female superheroes like Wonder Woman, though crafted to appeal to the fantasies of teenage boys, are also powerful because… well, they have superpowers.

Perhaps that’s one way to look at Bergeret’s cards. He is not mocking his subjects, nor hyper-sexualizing them, but presenting, as each card indicates, advanced futuristic beings who didn’t yet exist in his time. The Daily Mail captions several of the photos with factoids about women’s advances in French history. In some cases, Bergeret did not have to extrapolate far. Women could practice law in 1900; women served in the army during the French Revolution, but did not fight. Colleges had been open to women since 1879. A few women worked as doctors and journalists in Bergeret’s time. Marie Curie, you’ll recall, had discovered polonium, coined the term “radioactivity,” and would win the Nobel Prize in 1903. Queen Victoria had ruled over half the world.

But French women would have to wait several more decades to enter most of the professions represented. No matter how sexy—and in some cases ridiculous—some of the costumes in these photos, Bergeret shot the models with poise, style, and dignity. Perhaps he and many in his audience could easily imagine female generals, mayors, firewomen, soldiers, etc. Yet one particular card stands out. It portrays a self-satisfied, Bohemian model labeled “rapin”—which a reader below informs us is “an argot word for (bad) painter.”

Related Content:

In 1900, Ladies’ Home Journal Publishes 28 Predictions for the Year 2000

How French Artists in 1899 Envisioned Life in the Year 2000: Drawing the Future

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness