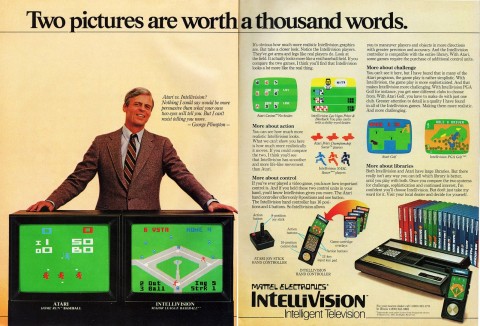

The beginning of the 1972 documentary Future Shock, directed by Alex Grasshof, shows Orson Welles, bearded and chomping on a cigar, standing on an airport people mover. He turns to the camera and delivers a monologue in his trademark silken baritone. “In the course of my work, which has taken me to just about every corner of the globe, I see many aspects of a phenomenon which I’m just beginning to understand. Our modern technologies have changed the degree of sophistication beyond our wildest dreams. But this technology has exacted a pretty heavy price. We live in an age of anxiety and time of stress. And with all our sophistication, we are in fact the victims of our own technological strengths –- we are the victims of shock… a future shock.”

The documentary itself is wonderfully dated. From its bizarre opening montage; to its soundtrack, which lurches from early electronic music to jazz funk; to some endearing video special effects, which, for whatever reason, mostly centers around Orson Welles’s head, the film feels thoroughly rooted in the Nixon administration. Yet many of the ideas discussed in the movie are, if anything, more relevant now than in the 1970s.

The term “future shock” was invented in Alvin Toffler’s hugely bestselling book of the same name to describe the constant, bewildering barrage of new technologies and all the resulting societal changes those technologies bring about. Anyone who has struggled to comprehend a new, baffling and supposedly essential social media platform, anyone who has been driven to paralysis over the number of choices on Netflix, anyone who found their livelihood decimated because of a hot new app knows what “future shock” is.

Toffler (along with his wife and uncredited co-writer Heidi Toffler) argued that we are in the midst of a massive structural change from an industrial society to a post-industrial one – a society that boggles the mind with an overload of information and an overload of consumer choices. “Change,” as they wrote, “is the only constant.”

Along the way, the Tofflers managed to predict the collapse of America’s manufacturing sector, along with things like Prozac, temp jobs, the internet and the meteoric rise and fall of insta-celebs (Alex from Target, we hardly knew you.) Other predictions – underwater cities, paper clothes and being able to choose your own skin color – haven’t yet come to pass. Still, they had a surprisingly good track record considering these predictions were written over four decades ago.

The video ends with a plea from not Welles, but Toffler himself, who is seen addressing college students.

If we can recognize that industrialism is not the only possible form of technological society, if we can begin to think more imaginatively about the future, then we can prevent future shock and we can use technology itself to build a decent, democratic and humane society. […] We can no longer allow technology just to come roaring down at us. We must begin to say “No” to certain kinds of technology and begin to control technological change, because we have now reached the point at which technology is so powerful and so rapid that it may destroy us, unless we control it. But what is the most important is we simply do not accept everything; that we begin to make critical decisions about what kind of world we want and what kind of technology we want.

Find other short films narrated by Welles in our collection, 4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More.

Related Content:

Isaac Asimov Predicts in 1964 What the World Will Look Like Today — in 2014

Arthur C. Clarke Predicts the Future in 1964 … And Kind of Nails It

Walter Cronkite Imagines the Home of the 21st Century … Back in 1967

The Internet Imagined in 1969

Marshall McLuhan Announces That The World is a Global Village

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow. And check out his blog Veeptopus, featuring lots of pictures of badgers and even more pictures of vice presidents with octopuses on their heads. The Veeptopus store is here.