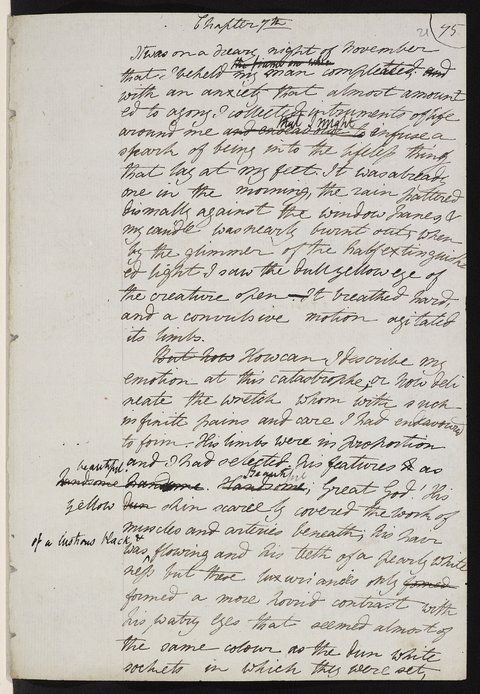

Sure, you enjoyed hearing the way Ancient Greek music actually sounded last week, but what about the way Ancient Greek poetry actually sounded? We can find fewer finer or more recognizable examples of the stuff than Homer’s Iliad, and above you can hear a reading of a section of the Iliad (Book 23, Lines 62–107 ) in the original Ancient Greek language.

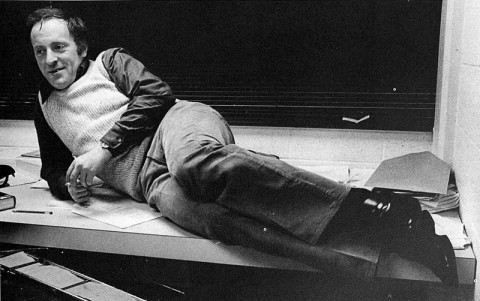

It comes from what may strike you as an unlikely source: Stanley Lombardo, a University of Kansas classicist (and also, as it happens, a Zen Buddhist) best known for his translations of the Iliad, the Odyssey, and Virgil’s Aeneid into contemporary-sounding English. “Sounding less like aristocratic warriors than like American G.I.‘s, perhaps,” writes classics-steeped critic Daniel Mendelsohn in the New York Times review of Lombardo’s Iliad, “his epic heroes ‘badmouth’ and ‘beat the daylights out of one another and witheringly call one another ‘trash’ and ‘pansy.’ ”

But Lombardo knows thoroughly the material he adapts. Even those of us who never learned Ancient Greek — if I may speak for this presumably large group of readers — can get a feel for Homer’s tale of the Trojan War and the soldiers’ long return home by listening to the professor’s delivery alone. Just above, you can see him give a reading from his English translation. It won’t surprise you to learn that he also reads the audio books. “We listened spellbound to the incantatory waves of Professor Stanley Lombardo’s voice telling the stories of Odysseus and his Odyssey and then those of the Trojan heroes of The Illiad,” writes Andrei Codrescu in an article on them for the Villager. “Professor Lombardo translated anew the immortal epics and immersed himself so deeply in their world his voice sounded as believable as the hills and valleys we crossed. His voice knows the tales and their enduring charms, and sounds for all the world like an ancient bard’s. Homer himself couldn’t have done better. In English no less, millennia later.”

Related Content:

What Ancient Greek Music Sounded Like: Hear a Reconstruction That is ‘100% Accurate’

Hear The Epic of Gilgamesh Read in the Original Akkadian, the Language of Mesopotamia

Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey: Free AudioBooks & eBooks

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on literature, film, cities, Asia, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.