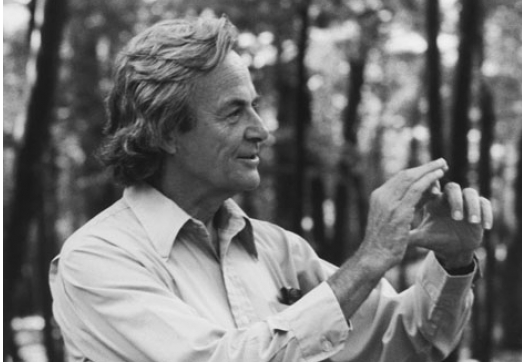

One of the treasures of our time, biologist E.O. Wilson, the folksy and brilliant author of two Pulitzer Prize-winning books and the world’s leading authority on ants, is 84 years old and retired from his professorship at Harvard. But even in retirement he came up with one of the most innovative new scientific resources available today: the Encyclopedia of Life, a networked encyclopedia of all the world’s knowledge about life.

Six years ago Wilson announced his vision for such a project while accepting the 2007 TED Prize. He expressed a wish for a collaborative tool to create an infinitely expandable page for each species—all 1.9 million known so far—where scientists around the world can contribute text and images.

Wilson’s dream came true, not long after he announced it, and the EOL was so popular right away that it had to go off-line for a spell to expand its capacity to handle the traffic. The site was redesigned to be more accessible and to encourage contributions from users. It’s vision: to continue to dynamically catalog every living species, as research is completed, and to include the roughly 20,000 new species discovered every year.

Wilson’s vision is manifest in a fun and well-designed site useful for educators, academics, and any curious person with access to the Internet.

Search for a species or just browse. Each EOL taxonomy page features a detailed overview of the species, research, articles and media. Media can be filtered by images, video, and sound. There are 66 different pieces of media about Tasmanian Devils, for example. A group of Tassies, as they’re known, get pretty devilish over their dinner in this video, contributed by an Australian Ph.D. student.

As E.O. Wilson so eloquently puts it, the EOL has the potential to inspire others to search for life, to understand it, and, most importantly, to preserve it.

Related Content:

E.O. Wilson’s Olive Branch: The Creation

Central Intelligence: From Ants to the Web

Kate Rix writes about digital media and education. Follow her on Twitter.