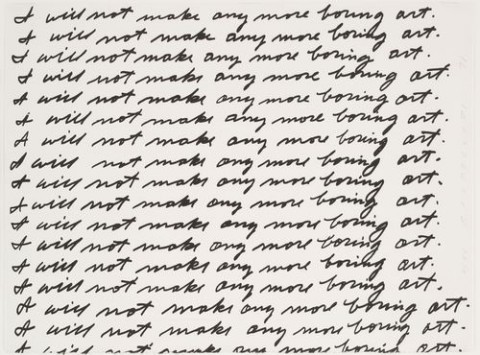

There are any number of ways to take artist John Baldessari’si 1971 piece I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art, so why not a DIY MOOC? No registration required and no course credit. Students who watch the entire 13-minute video above will receive certificates of completion, provided they’re willing to write them out themselves on lined notebook paper. (It’s really not that far fetched in an age where thousands of unofficial students recently took advantage of cartoonist Lynda Barry’s willingness to tweet her assignments for her Unthinkable Mind course at the University of Wisconsin.)

If you’re on the fence about the merits of Conceptual Art, you may be swayed to learn the history of the piece documented above. The year before its creation, John Baldessari incinerated his oeuvre, an act he referred to as The Cremation Project. Shortly thereafter, he responded to Nova Scotia College of Art and Design’s invitation to exhibit with a letter instructing students to be his surrogates in a punishment piece:

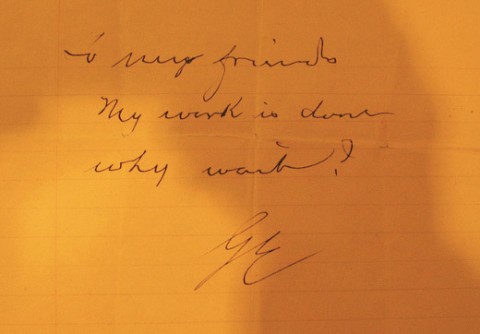

The piece is this, from floor to ceiling should be written by one or more people, one sentence under another, the following statement: I will not make any more bad art. At least one column of the sentence should be done floor to ceiling before the exhibit opens and the writing of the sentence should continue everyday, if possible, for the length of the exhibit. I would appreciate it if you could tell me how many times the sentence has been written after the exhibit closes. It should be hand written, clearly written with correct spelling….

Once the students had punished themselves to his specifications, the artist permitted the school to publish a fundraising lithograph, modeled on his handwriting.

It’s not a stretch to imagine that writing this sentence over and over could have changed more than a few participants’ lives, or at least rerouted the path their careers would take. What will happen if you take 13 minutes—the length of the video above—to try it yourself.

Related Content:

Join Cartoonist Lynda Barry for a University-Level Course on Doodling and Neuroscience

A Brief History of John Baldessari, Narrated by Tom Waits

Yoko Ono’s Make-Up Tips for Men

Ayun Halliday will wade through the boring in search of the good. Follow her @AyunHalliday