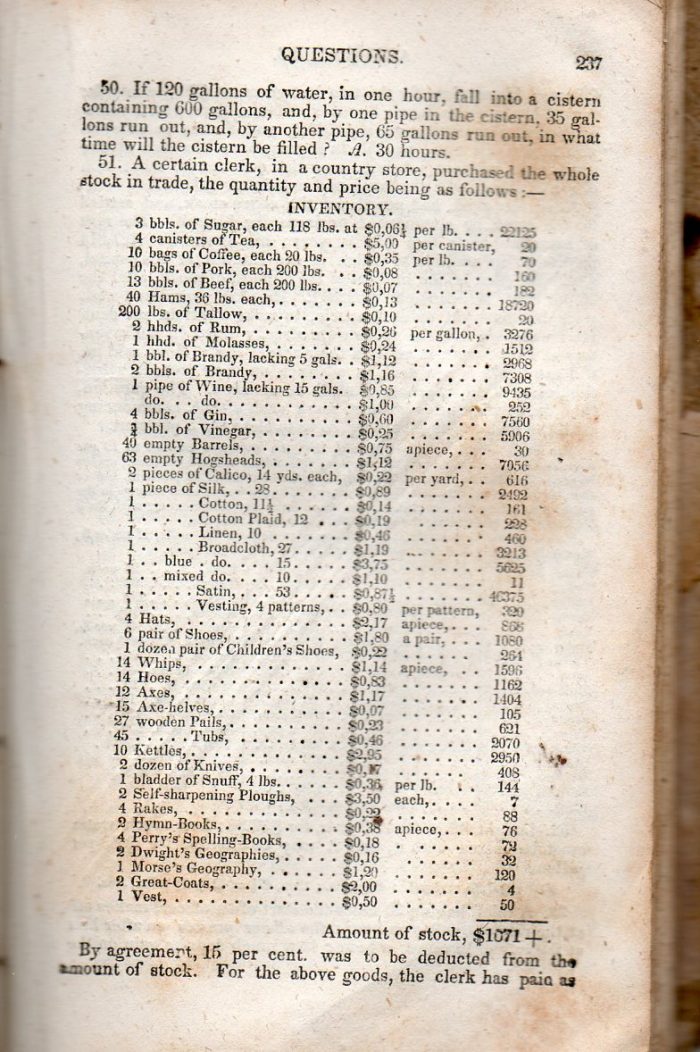

Click here to view the image in a larger format.

Like many children in possession of a toy cash register, I was a big fan of playing store.

A short stint working retail in a 90’s era Chicago hippie clothing emporium cured me of that for the most part.

But looking over the above page from Roswell C. Smith’s 1836 Practical and Mental Arithmetic on a New Plan, I must admit, I feel some of the old stirrings, and not because I love math, even when it’s intended to be worked on a slate.

Coffee, 35 cents per pound. A self-sharpening plough, $3.50. A whip, a buck fourteen. And a gallon of gin, 60 cents, which was “about two-thirds of a day’s wages for the average non-farm white male worker.” (View the prices in a larger format here.)

But I’m less intrigued by the wholesale price of the various items Smith’s hypothetical country storekeeper would pay to stock his shelves in 1836, though I do love a bargain.

It’s more the type of goods listed on that inventory. They’re exactly the sort of items that figure in one of the most memorable chapters of Little House on the Prairie—“Mr Edwards Meets Santa Claus.”

Okay, so maybe not exactly the same. Author Laura Ingalls Wilder was pretty explicit about the simple pleasures of her 1870s and 80s childhood. Her family’s bachelor neighbor, Mr. Edwards, risked life and limb fording a near-impassable, late-December creek, a bundle containing his clothes, a couple of tin cups, some peppermint sticks, and two heart-shaped cakes, tied to his head. Without his kindly initiative, their stockings would have been empty that year.

Presumably, the Independence, Kansas general store where Neighbor Edwards did his Christmas shopping would’ve stocked a lot of the same merch’ that Smith alludes to in the above fragment of a bookkeeping-related story problem. Online bookseller John Ptak, on whose blog the page was originally reproduced, is keeping page 238 close to the vest (coincidentally the last item to be mentioned on the inventory, almost as an afterthought, just one, priced at 50¢.)

Childhood recollections aside, perhaps there was something else in Mr. Edward’s bundle, something the adult Laura chose not to mention. The sort of hostess gift that could’ve warmed Pa and Ma on those long, cold frontier nights…

Some gin, perhaps…or wine? Rum? Brandy?

Smith’s shopkeeper would’ve been well provisioned, laying the stuff in by the barrel, hogshead, and pipe-full.

As for that “bladder” of snuff, a post on the Snuffhouse forum suggests that it wasn’t a euphemism, but the actual bladder of a hog, paced with 4 pounds of snortin’ tobacco.

Of course, Smith’s shopkeeper would’ve also carried a healthy assortment of wholesome goods- hymnals, children’s shoes, calico, satin, whips…

Perhaps we should do the math.

Related Content:

Enter an Archive of 6,000 Historical Children’s Books, All Digitized and Free to Read Online

19th Century Maps Visualize Measles in America Before the Miracle of Vaccines

Thomas Jefferson’s Handwritten Vanilla Ice Cream Recipe

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday