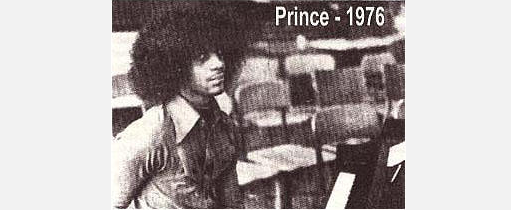

Two years before Prince released his first album For You and before he began his ascent into the funk-rock-pop pantheon, he was a very talented, very ambitious, and occasionally frustrated high school senior at Central High in Minneapolis. That’s where the school newspaper got him to sit for an interview, more of a character sketch, to talk about his hopes for a musical career. You can read it below.

If Prince was charismatic enough to be picked up on the high school paper’s radar, he doesn’t let it show in the article.

Mostly, he rues the location of his home town.

“I think it is very hard for a band to make it in this state, even if they’re good. Mainly because there aren’t any big record companies or studios in this state. I really feel that if we would have lived in Los Angeles or New York or some other big city, we would have gotten over by now.”

By the ‘80s, of course, he had made Minneapolis the center of his own musical empire, and Paisley Park became his home, compound, and music studio, the place where he would eventually pass away.

But he did like high school, according to him, because the music teachers let him do his own thing. Already a multi-instrumentalist, the article finds Prince just starting to explore singing. This might be the most surprising part of the piece. Prince’s range and the amount of character (and literally characters, male, female, or a mix) in his songs would lead you to believe that his voice came first.

Maybe some of the humility came from his status in the high school band. The name Grand Central was inspired by Prince’s obsession with Graham Central Station, whose bass player Larry Graham would later join Prince’s ‘90s band and also convert him to become a Jehovah’s Witness. Competing for attention was Morris Day and André Cymone, who Prince would write for and produce after he got his record contract. It was friendly but serious competition.

To round out the article, Prince—who plays by ear—gets asked if he has any advice for fellow students: “I advise anyone who wants to learn guitar to get a teacher unless they are very musically inclined. One should learn all their scales too. That is very important.”

You can read the full article below:

Nelson Finds It “Hard To Become Known”

“I play with Grand Central Corporation. I’ve been playing with them for two years,” Prince Nelson, senior at Central, said. Prince started playing piano at age seven and guitar when he got out of eighth grade.

Prince was born in Minneapolis. When asked, he said, “I was born here, unfortunately.” Why? “I think it is very hard for a band to make it in this state, even if they’re good. Mainly because there aren’t any big record companies or studios in this state. I really feel that if we would have lived in Los Angeles or New York or some other big city, we would have gotten over by now.”

He likes Central a great deal, because his music teachers let him work on his own. He now is working with Mr. Bickham, a music teacher at Central, but has been working with Mrs. Doepkes.

He plays several instruments, such as guitar, bass, all keyboards, and drums. He also sings sometimes, which he picked up recently. He played saxophone in seventh grade but gave it up. He regrets he did. He quit playing sax when school ended one summer. He never had time to practice sax anymore when he went back to school. He does not play in the school band. Why? “I really don’t have time to make the concerts.”

Prince has a brother that goes to Central whose name is Duane Nelson, who is more athletically enthusiastic. He plays on the basketball team and played on the football team. Duane is also a senior.

Prince plays by ear. “I’ve had about two lessons, but they didn’t help much. I think you’ll always be able to do what your ear tells you, so just think how great you’d be with lessons also,” he said.

“I advise anyone who wants to learn guitar to get a teacher unless they are very musically inclined. One should learn all their scales too. That is very important,” he continued.

Prince would also like to say that his band is in the process of recording an album containing songs they have composed. It should be released during the early part of the summer.

“Eventually I would like to go to college and start lessons again when I’m much older.”

via That Eric Alper

Related Content:

Hear Prince and Miles Davis’ Rarely-Heard Musical Collaborations

Prince Plays Mind-Blowing Guitar Solos On “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” and “American Woman”

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the FunkZone Podcast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, read his other arts writing at tedmills.com and/or watch his films here.