I recently heard someone say his college-bound nephew asked him, “What’s a union?” Whether you love unions, loathe them, or remain indifferent, the fact that an ostensibly educated young person might have such a significant gap in their knowledge should cause concern. A historic labor conflict, after all, provided the occasion for Ronald Reagan to prove his bona fides to the new conservative movement that swept him into power. His crushing of the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO) in 1981 set the tone for the ensuing 30 years or so of economic policy, with the labor movement fighting an uphill battle all the way. Prior to that defining event, unions held sway over politics local and national, and had consolidated power blocks in the American political landscape through decades of struggle against oppressive and dehumanizing working conditions.

In practical terms, unions have stood in the way of capital’s unceasing search for cheap labor and new consumer markets; in social and cultural terms, the politics of labor have represented a formidable ideological challenge to conservatives as well, by way of a vibrant assemblage of anarchists, civil libertarians, anti-colonialists, communists, environmentalists, pacifists, feminists, socialists, etc. A host of radical isms flourished among organized workers especially in the decades between the 1870s and the 1970s, finding their voice in newsletters, magazines, pamphlets, leaflets, and posters—fragile mediums that do not often weather well the ravages of time. Thus the advent of digital archives has been a boon for students and historians of workers’ movements and other populist political groundswells. One such archive, the Joseph A. Labadie Collection at the University of Michigan Library, has recently announced the digitization of over 2,200 posters from their collection, a database that spans the globe and the spectrum of leftist political speech and iconography.

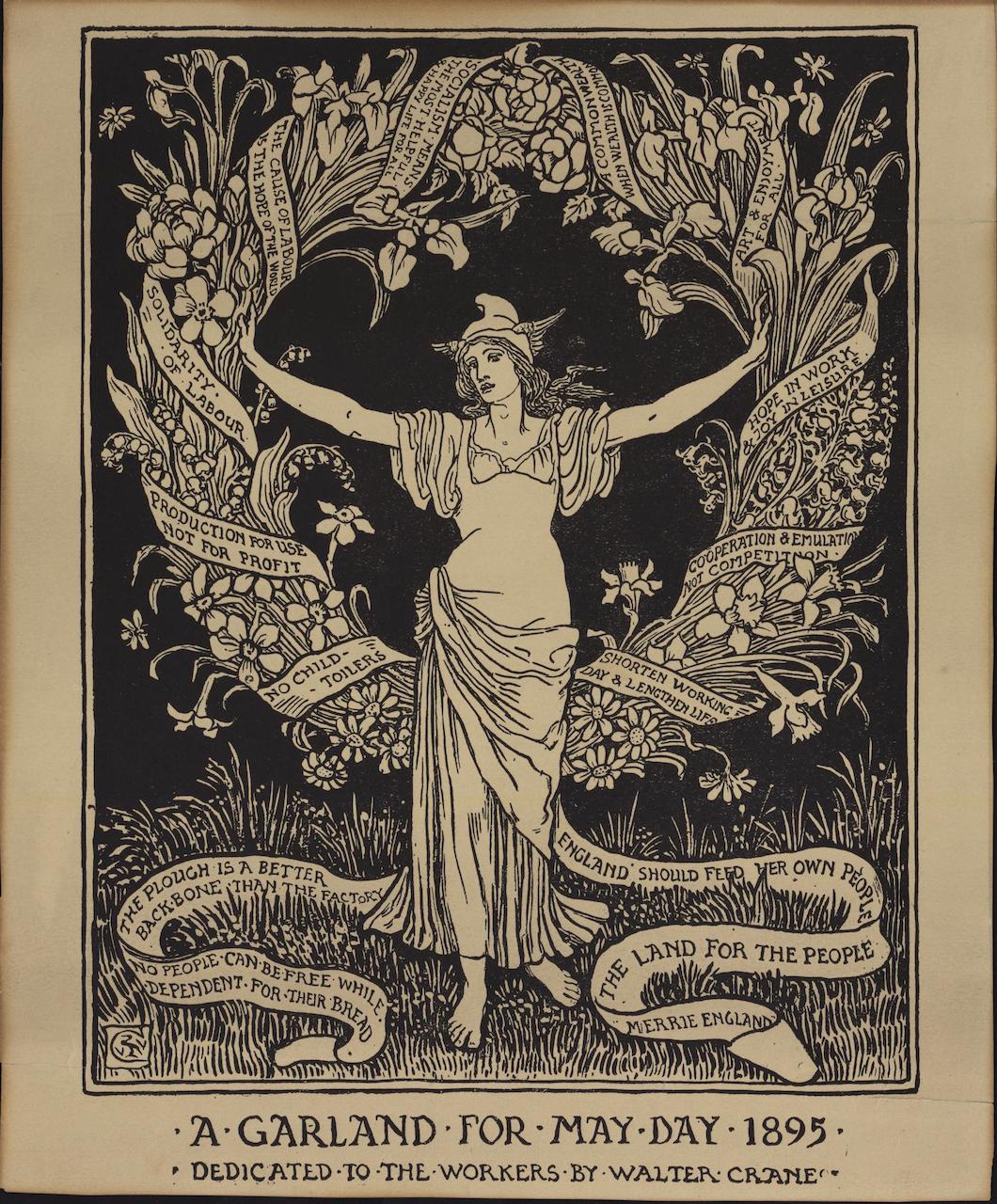

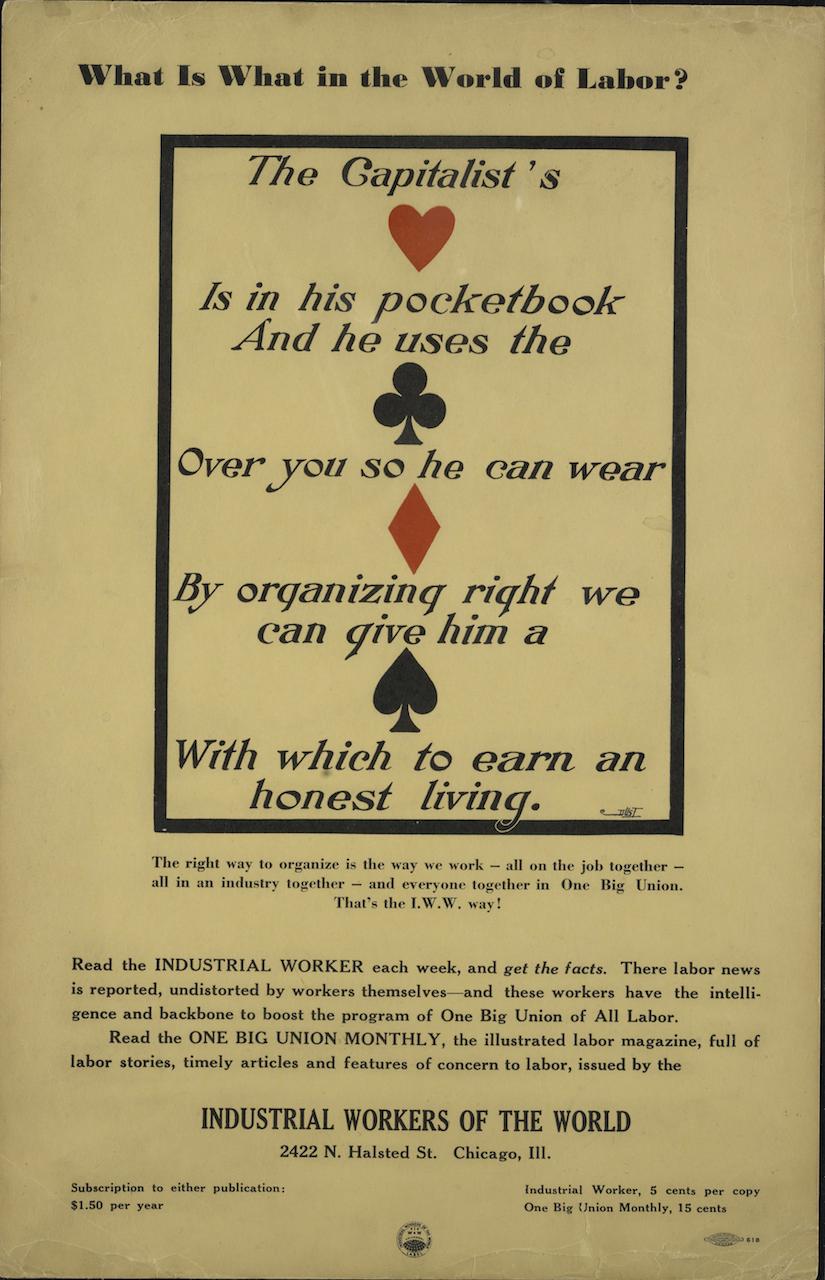

We have cleverly-designed visual puns like the Chicago Industrial Workers of the World poster just above, titled “What is what in the world of labor?” Promoting itself as “One Big Union of All Labor,” the IWW made some of the most ambitious propaganda, like the 1912 poster (middle) in which an “Industrial Co-Operative Commonwealth” replaces the tyranny of the capitalist, who is told by his “trust manager” peer, “Our rule is ended, dismount and go to work.” In this post-revolutionary fantasy, the IWW promises that “A few hours of useful work insure all a luxurious living,” though it only hints at the details of this utopian arrangement. Up top, we have an ornate May Day poster from 1895 by Walter Crane, hoping for a “Merrie England” with “No Child Toilers,” “Production for Use Not For Profit,” and “The Land For the People,” among other, more nationalist, sentiments like “England Should Feed Her Own People.”

“While all of the posters were scanned at high resolution,” writes Hyperallergic, “they appear online as thumbnails with navigation to zoom.” You can download the images, but only the smaller, thumbnail size in most cases. These hundreds of posters represent “just a portion of the material in the Labadie Collection”—named for a “Detroit-area labor organizer, anarchist, and author” who “had the idea for the social protest archive at the university in 1911.” You can view other political artifacts in the UMich library’s digital collections here, including anarchist pamphlets, political buttons, and a digital photo collection. The collection as a whole gives us a potentially inspiring, or infuriating, mosaic of political thought at its boldest and most graphically assertive from a time before online petitions and hashtag campaigns took over as the primary circulators of popular radical thought.

via Hyperallergic (where you can find some other big, visually striking posters)

Related Content:

Wonderfully Kitschy Propaganda Posters Champion the Chinese Space Program (1962–2003)

Free Online Political Science Courses

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness