Everyone who knows the work of Ernest Hemingway knows A Farewell to Arms, and everyone who knows A Farewell to Arms knows that Hemingway drew on his experience as a Red Cross ambulance driver in Italy during World War I. Just a few months after shipping out, the eighteen-year-old writer-to-be — filled, he later said, with “a great illusion of immortality” — got caught by mortar fire while taking chocolate and cigarettes from the canteen to the front line. Recovering from his wounds in a Milanese hospital, he fell in love with an American nurse named Agnes Hannah von Kurowsky, who would become the model for Catherine Barkley in A Farewell to Arms.

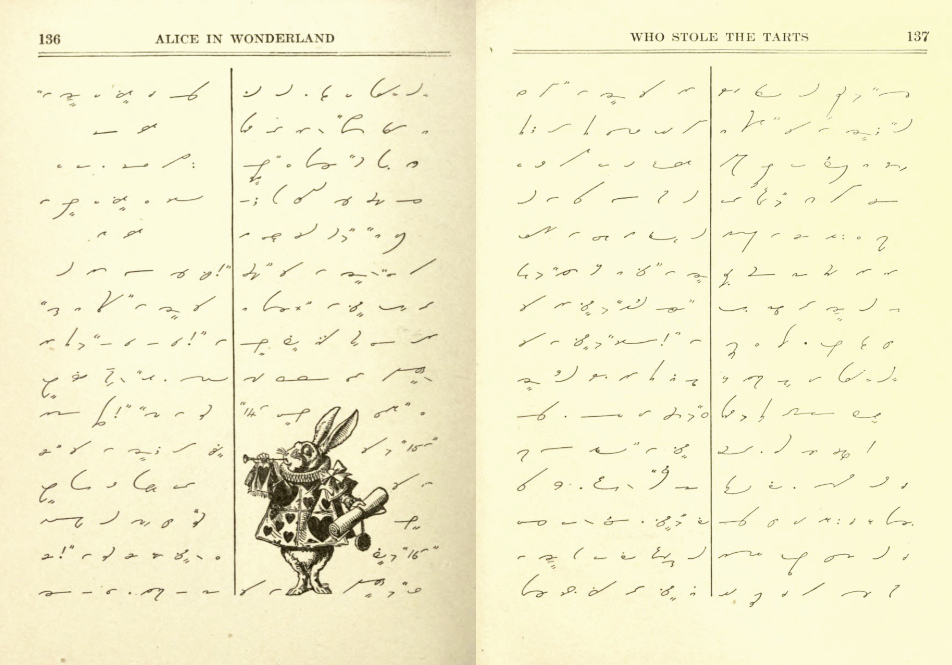

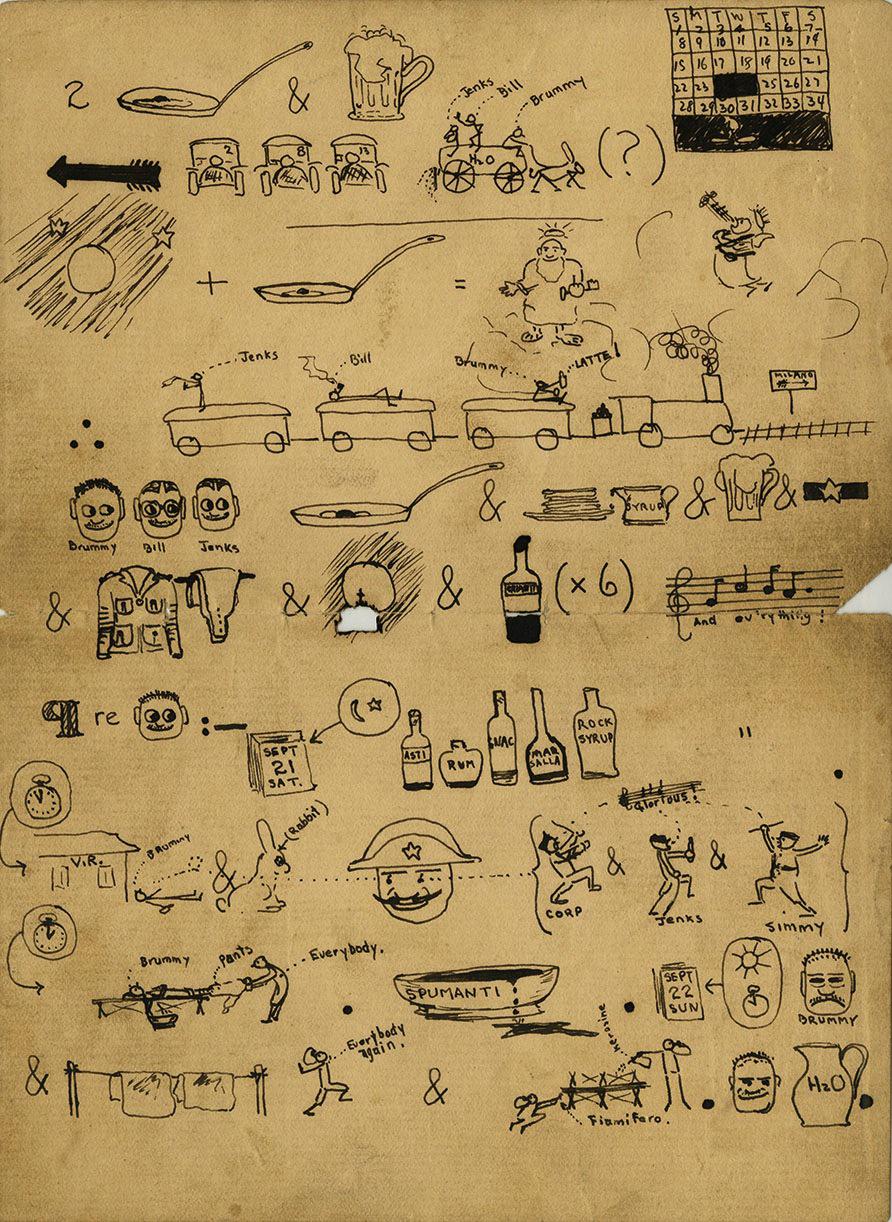

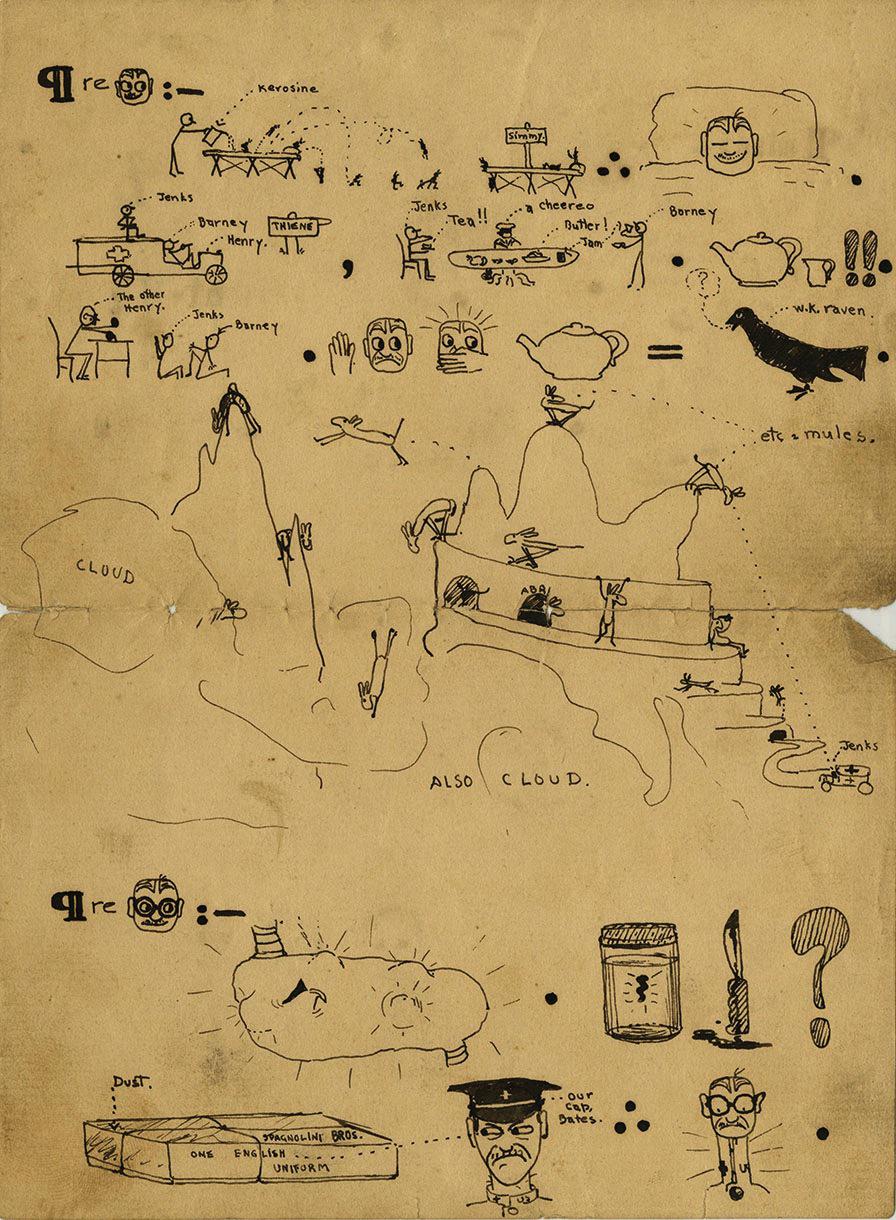

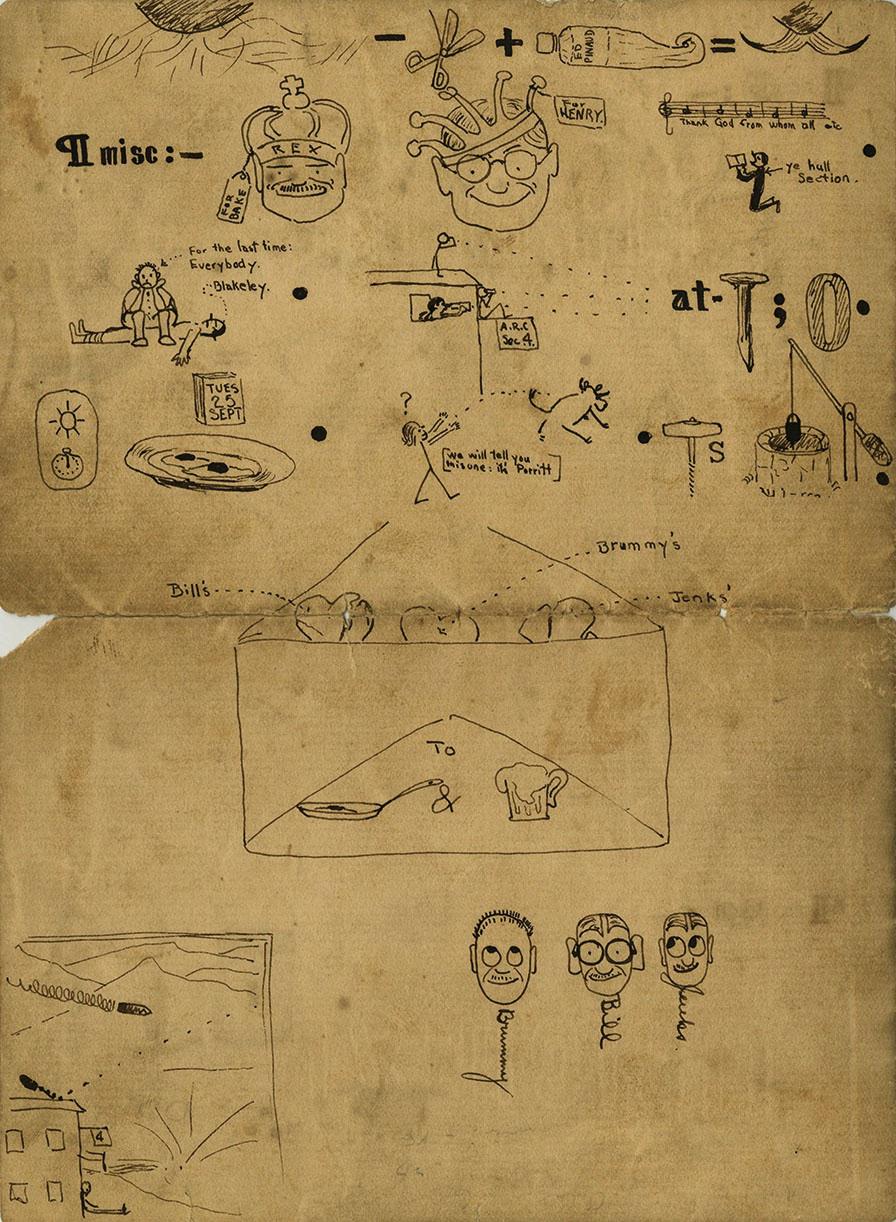

Hemingway wrote that novel years after Kurowsky had left him for an Italian officer, but when their prospects still looked good, they received this curious letter, which at first glance looks like nothing more than a few pages of doodles. “We think it may be a rebus or another type of pictogram that uses pictures to represent words, parts of words, or phrases,” wrote Jessica Green, an intern at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library where it turned up, in 2012. “Can you help us solve this puzzle?” Quite a few Hemingway-enthusiast commenters dutifully got to their interpretive work below Green’s post, bringing to bear their knowledge of the writer’s life and work on these animals, musical notes, grinning faces, and mugs of beer, all strung together with logic symbols.

If you need a hint, you might start with the apparent fact that the letter came from three of Hemingway’s ambulance-driver buddies. “The letter is a cheerful narrative of the three friends’ recent hijinks,” writes Slate’s Rebecca Onion. “In the salutation, the writers used a foaming mug of beer to represent Hemingway’s name (he was often called ‘Hemingstein’); clearly, these were men who shared Hemingway’s love for inebriation.” But even before they addressed good old Hemingstein, they addressed Kurowsky — as, in the visual language invented for their purposes, a frying pan with an egg in it. “Ag sounds like egg,” explains the decipherment Green later posted to the JFK Library’s blog.

Green goes on to break down the pictographic letter section by section, from Brummy, Bill, and Jenks’ plans to take leave time and come to Milan, Brummy’s unfortunate recent experience with “mixed drinks made from Asti Spumanti, Rum, Cognac, Marsala, and Rock Syrup,” Jenks’ driving of the bedbugs in his bed into that of another driver, and the glorious results of Bill’s trimming and waxing of his mustache, and more besides. To modern readers, the letter offers not just a glimpse into the sensibilities of Hemingway’s social circle but life on the Italian front in 1918. And for Hemingway himself, receiving such an amusing piece of correspondence during six long months of recuperation in the hospital must surely have done something to lift the spirits, though what effect its distinctive compositional style may have had on his own writing seemingly remains to be studied.

Click here to read a decoding of this pictogram from 1918.

Related Content:

Ernest Hemingway’s Very First Published Stories, Free as an eBook

Ernest Hemingway Creates a Reading List for a Young Writer (1934)

Seven Tips From Ernest Hemingway on How to Write Fiction

Hear Hemingway Read Hemingway, and Faulkner Read Faulkner (90 Minutes of Classic Audio)

Ernest Hemingway’s Favorite Hamburger Recipe

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.