After the great director F.W. Murnau died in a car crash in California at the young age of 42, his body was flown back to his native Germany to be buried, and that’s where he has rested since 1931.

Until this week, that is, when somebody made off with the director’s skull.

Reports are sketchy and rely on this report from German news outlet BZ, but, according to police, somebody opened up Murnau’s metal coffin and removed the head from the embalmed corpse. Wax and a candle were found at the scene, suggesting to some that the theft had occult ties.

It’s not the first time that Murnau’s grave has been disturbed. The coffin was vandalized in the 1970s, but this time the theft has Olaf Ihlefeldt, the cemetery’s manager, calling it a scandal. (The cemetery also holds the bodies of composer Engelbert Humperdinck and Bauhaus School member Walter Gropius.)

It’s rare for an artist’s grave to be robbed–fans prefer to cover gravestones with meaningful graffiti–while it is world leaders that usually get their bits stolen, like Geronimo’s skull, Mussolini’s brain, and, for some reason, Napoleon’s penis.

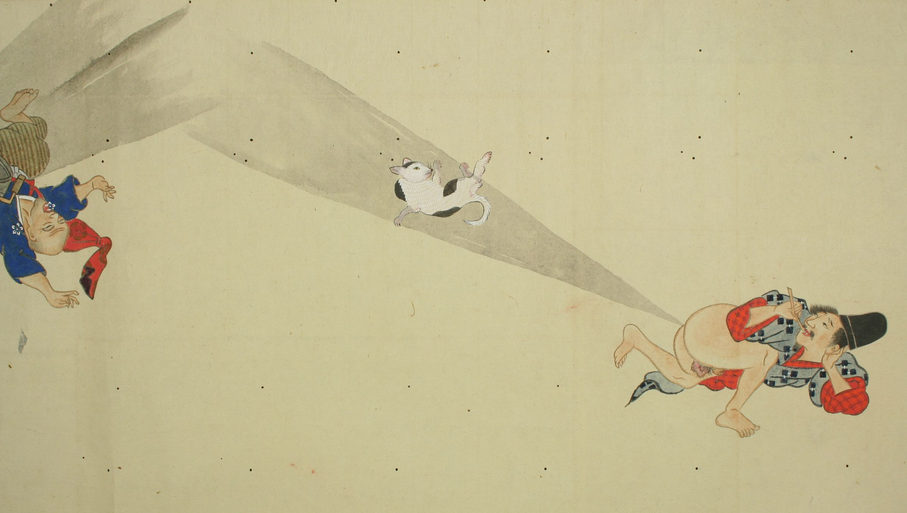

Murnau is best known for the spookiest Dracula tale ever told in celluloid, 1922’s Nosferatu, which had coffins aplenty. It is also, by the way, free to view above. He also delved into the Satanic with his version of Faust (1926), which features a marching band of skeletons, among other apparitions:

Murnau’s filmography contains a 1920 version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and The Hunchback and the Dancer from the same year, though both films are lost. The director did tend towards horror, but two of his finest films did not.

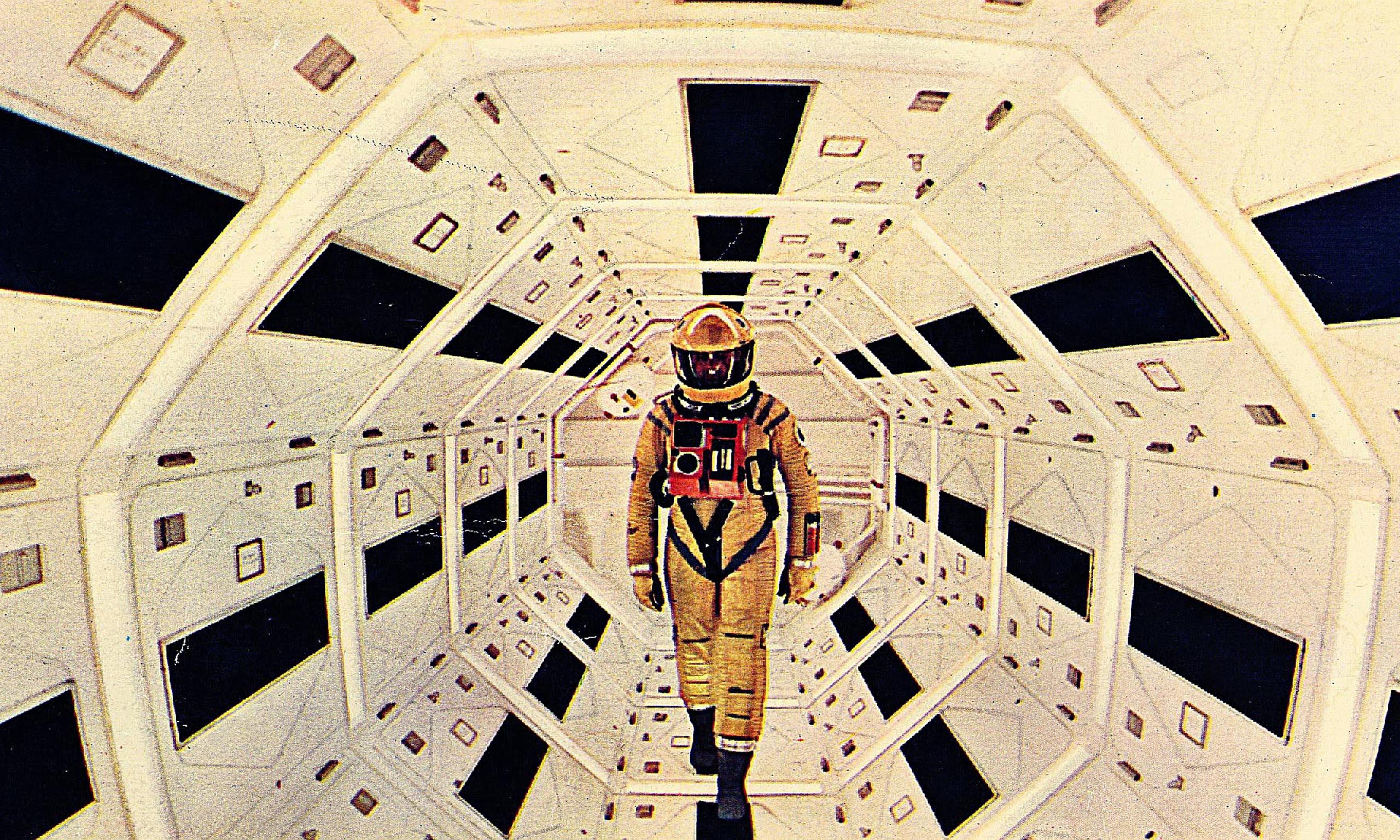

The Last Laugh (1924) is a poignant tale about a hotel doorman who can’t bear the shame of being fired, and contains one of cinema’s finest “director ex machina” with an improbable but happy ending. Once Murnau moved to Hollywood, he directed Sunrise (1927), which blended the director’s expressionistic style with a Tinsel Town budget, a tale of a love nearly lost then resurrected. Four years and another three films later, Murnau’s career would be over. He died in a Santa Barbara hospital after a traffic accident by the Rincon–now a famous surfing location–just a few miles from where I now write these words, 84 years later.

You can find Murnau’s films added to our collection, 4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More.

Related Content:

Free: F. W. Murnau’s Sunrise, the 1927 Masterpiece Voted the 5th Best Movie of All Time

101 Free Silent Films: The Great Classics

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the FunkZone Podcast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, read his other arts writing at tedmills.com and/or watch his films here.