Carl Sagan had his first religious experience at the age of five. Unsurprisingly, it was rooted in science. Sagan, then living in Brooklyn, had started pestering everyone around him about what stars were, and had grown frustrated by his inability to get a straight answer. Like the resourceful five-year-old that he was, the young Sagan took matters into his own hands and proceeded to the library:

“I went to the librarian and asked for a book about stars … And the answer was stunning. It was that the Sun was a star but really close. The stars were suns, but so far away they were just little points of light … The scale of the universe suddenly opened up to me. It was a kind of religious experience. There was a magnificence to it, a grandeur, a scale which has never left me. Never ever left me.”

This sense of universal wonder would eventually lead Sagan to become a well-known astronomer and cosmologist, as well as one of the 20th century’s most beloved science educators. Although he passed away in 1996, aged 62, Sagan’s legacy remains alive and well. This March, a reboot of his famed 1980 PBS show, Comos: A Personal Voyage, will appear on Fox, with the equally great science popularizer Neil DeGrasse Tyson taking Sagan’s role as host. Meanwhile, last November saw the opening of the Carl Sagan and Ann Druyan Archive at the Library of Congress.

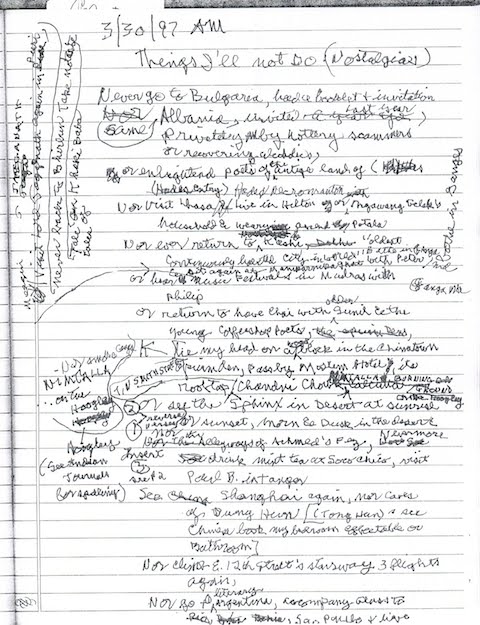

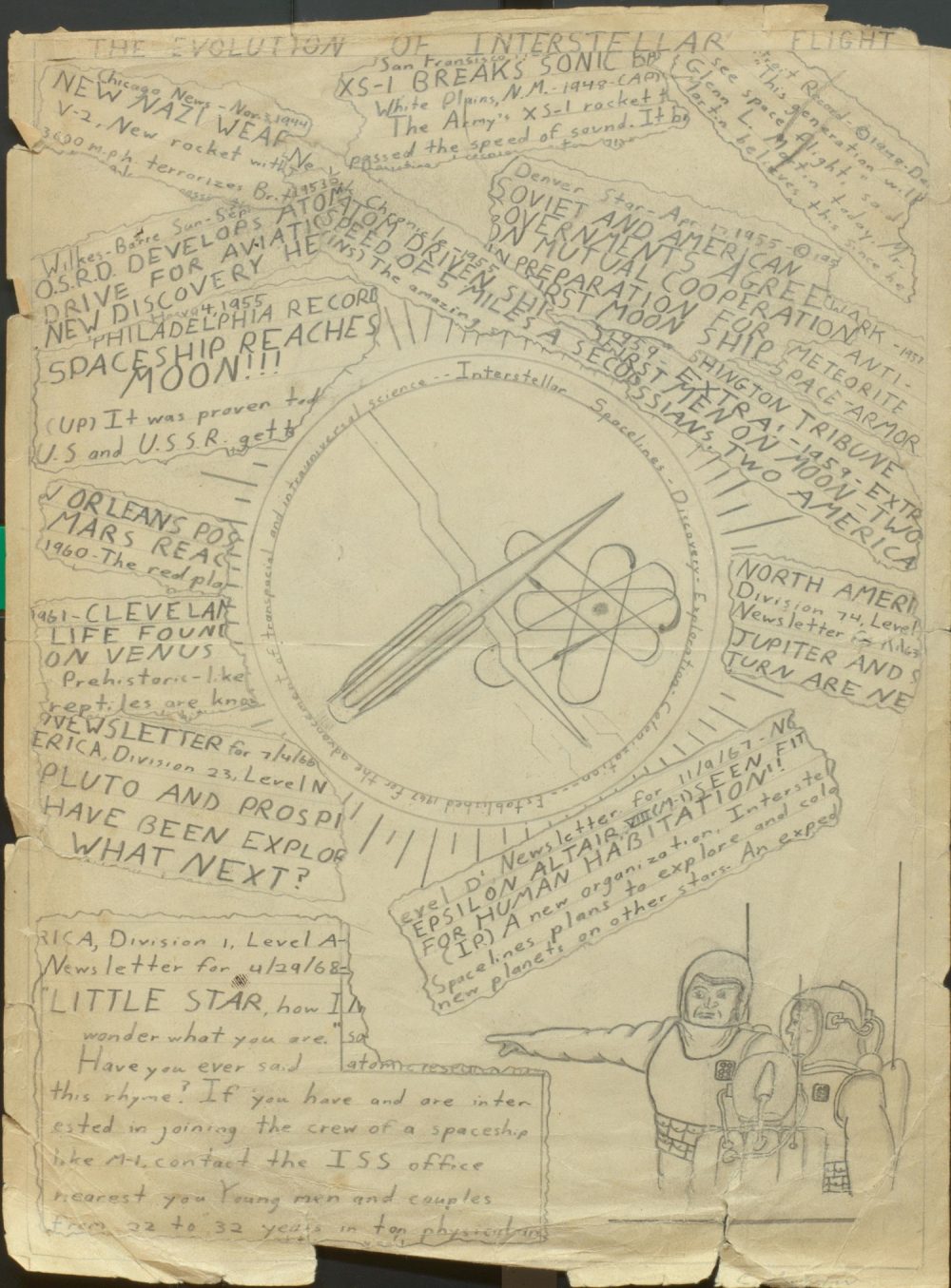

Among the papers in the archive was this sketch, titled “The Evolution of Interstellar Flight,” which Sagan drew between the ages of 10 and 13. In the center of the drawing Sagan pencilled the logo of Interstellar Spacelines, which, Sagan imagined, was “Established [in] 1967 for the advancement of transpacial and intrauniversal science.” Its motto? “Discovery –Exploration – Colonization.” Surrounding the logo, Sagan drew assorted newspaper clippings that he imagined could herald the key technological advancements in the space race. Impressively drawn astronauts in the corner aside, I most enjoyed the faux-clipping that read “LIFE FOUND ON VENUS: Prehistoric-like reptiles are…” Good luck containing your sense of wonder on seeing that.

Ilia Blinderman is a Montreal-based culture and science writer. Follow him at @iliablinderman.

Related Content:

Carl Sagan’s Undergrad Reading List: 40 Essential Texts for a Well-Rounded Thinker

Carl Sagan Presents Six Lectures on Earth, Mars & Our Solar System … For Kids (1977)

Carl Sagan, Stephen Hawking & Arthur C. Clarke Discuss God, the Universe, and Everything Else