The phrase “opening of Japan” is a euphemism that has outlived its purpose, serving to cloud rather than explain how a country closed to outsiders suddenly, in the mid-19th century, became a major influence in art and design worldwide. Negotiations were carried out at gunpoint. In 1853, Commodore Matthew Perry presented the Japanese with two white flags to raise when they were ready to surrender. (The Japanese called Perry’s fleet the “black ships of evil men.”) In one of innumerable historical ironies, we have this ugliness to thank for the explosion of Impressionist art (van Gogh was obsessed with Japanese prints and owned a large collection) as well as much of the beauty of Art Nouveau and modernist architecture at the turn of the century.

We may know versions of this already, but we probably don’t know it from a Japanese point of view. “As our global society grows ever more connected,” writes Katie Barrett at the Internet Archive blog, “it can be easy to assume that all of human history is just one click away. Yet language barriers and physical access still present major obstacles to deeper knowledge and understanding of other cultures.”

Unless we can read Japanese, our understanding of its history will always be informed by specialist scholars and translators. Now, at least, thanks to cooperation between the University of Tokyo General Library and the Internet Archive, we can access thousands more primary sources previously unavailable to “outsiders.”

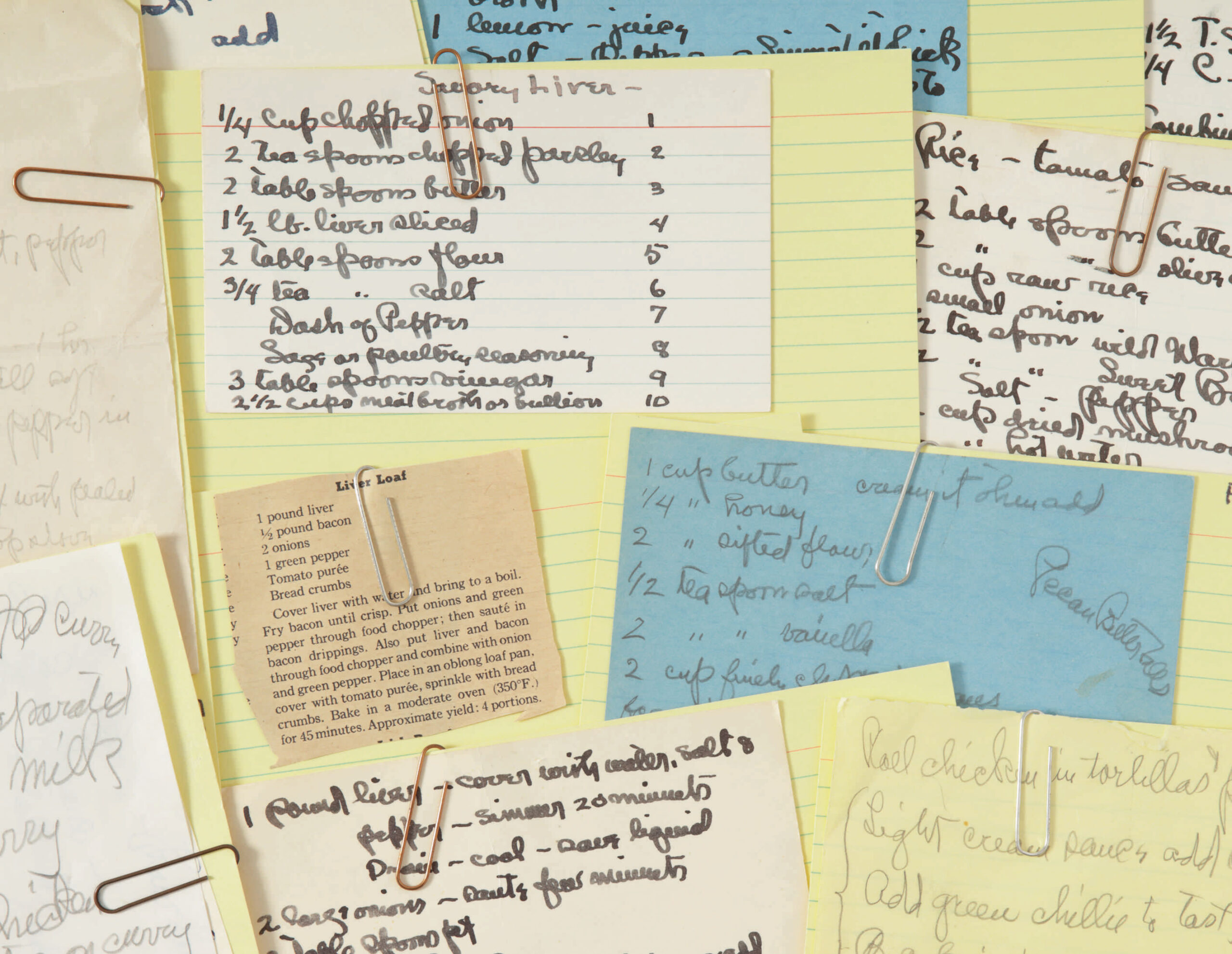

“Since June 2020,” notes Barrett, “our Collections team has worked in tandem with library staff to ingest thousands of digital files from the General Library’s servers, mapping the metadata for over 4,000 priceless scrolls, texts, and papers.” This material has been digitized over decades by Japanese scholars and “showcases hundreds of years of rich Japanese history expressed through prose, poetry, and artwork.” It will be primarily the artwork that concerns non-Japanese speakers, as it primarily concerned 19th-century Europeans and Americans who first encountered the country’s cultural products. Artwork like the humorous print above. Barrett provides context:

In one satirical illustration, thought to date from shortly after the 1855 Edo earthquake, courtesans and others from the demimonde, who suffered greatly in the disaster, are shown beating the giant catfish that was believed to cause earthquakes. The men in the upper left-hand corner represent the construction trades; they are trying to stop the attack on the fish, as rebuilding from earthquakes was a profitable business for them.

There are many such depictions of “seismic destruction” in ukiyo‑e prints dating from the same period and the later Mino-Owari earthquake of 1891: “They are a sobering reminder of the role that natural disasters have played in Japanese life.”

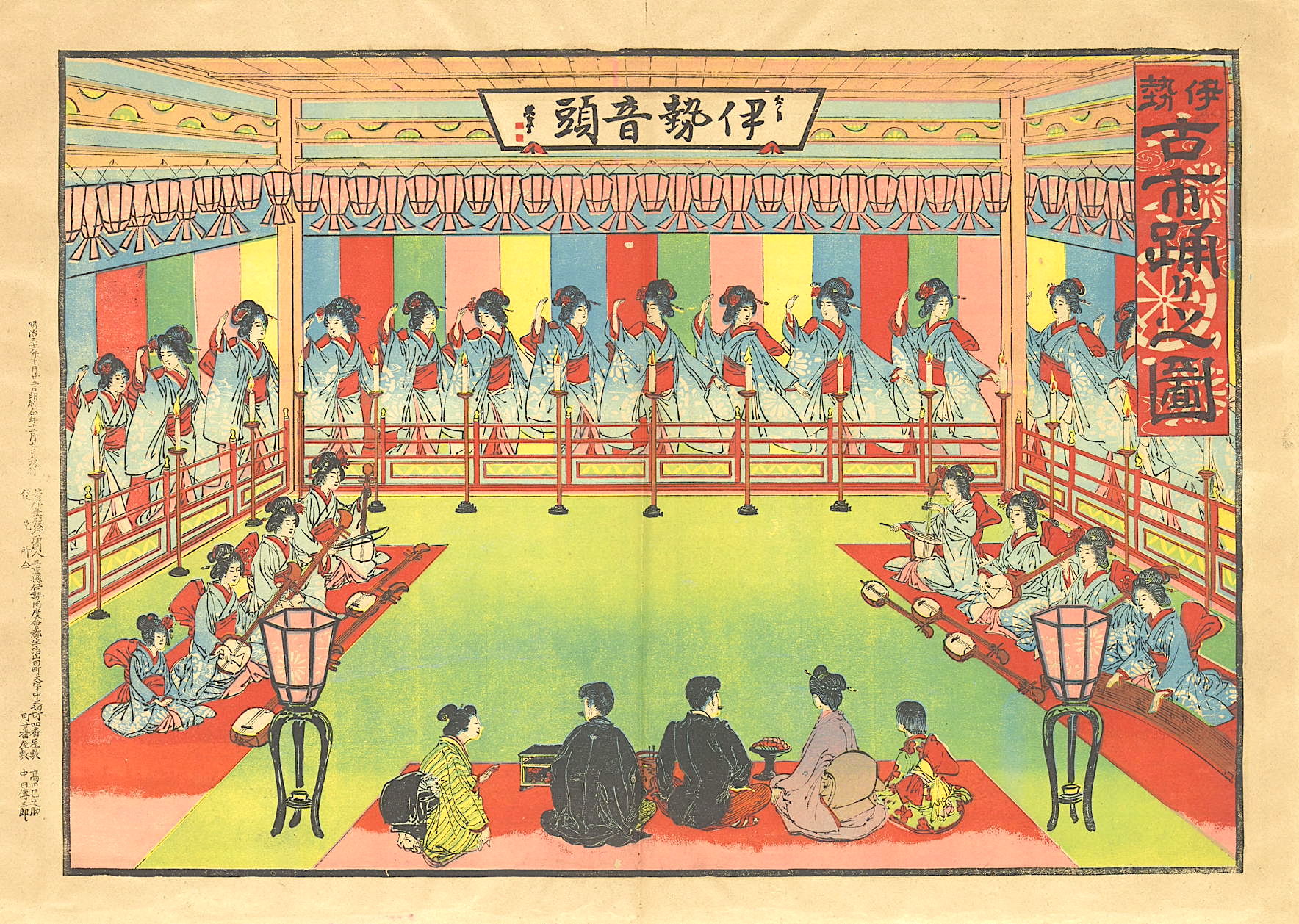

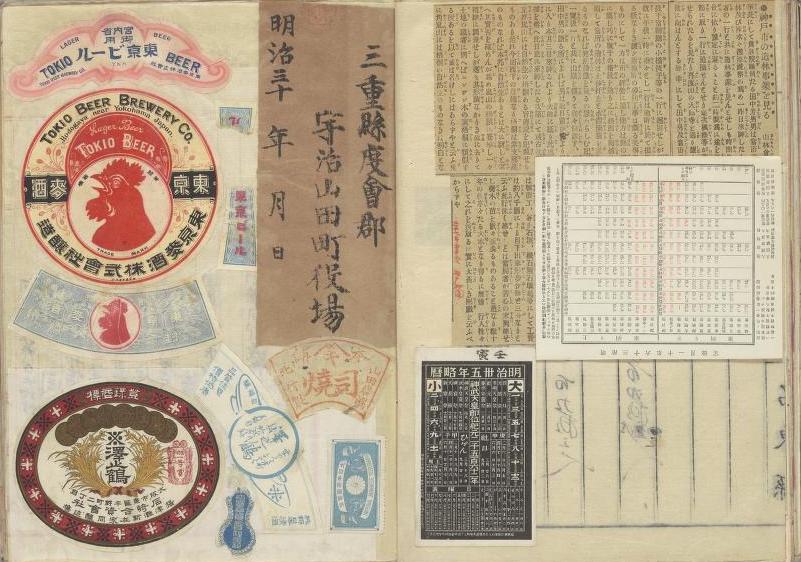

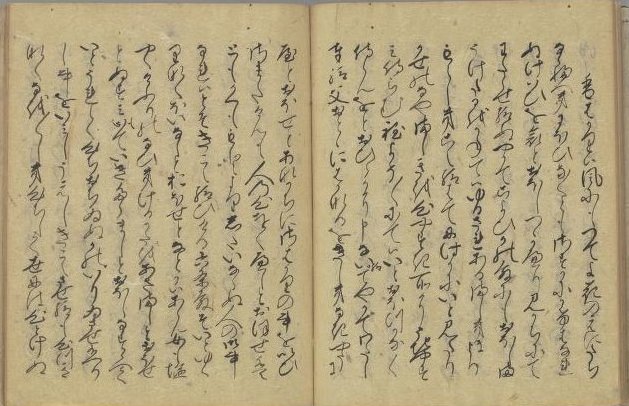

You can see many more digitized artifacts, such as the charming book of Japanese ephemera above, at the Internet Archive’s University of Tokyo collection. Among the 4180 items currently available, you’ll also find many European prints and engravings held in the library’s 25 collections. All of this material “can be used freely without prior permission,” writes the University of Tokyo Library. “Among the highlights,” Barrett writes, “are manuscripts and annotated books from the personal collection of the novelist Mori Ōgai (1862–1922), an early manuscript of the Tale of Genji, [below] and a unique collection of Chinese legal records from the Ming Dynasty.” Enter the collection here.

Related Content:

Watch Vintage Footage of Tokyo, Circa 1910, Get Brought to Life with Artificial Intelligence

Download Classic Japanese Wave and Ripple Designs: A Go-to Guide for Japanese Artists from 1903

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness