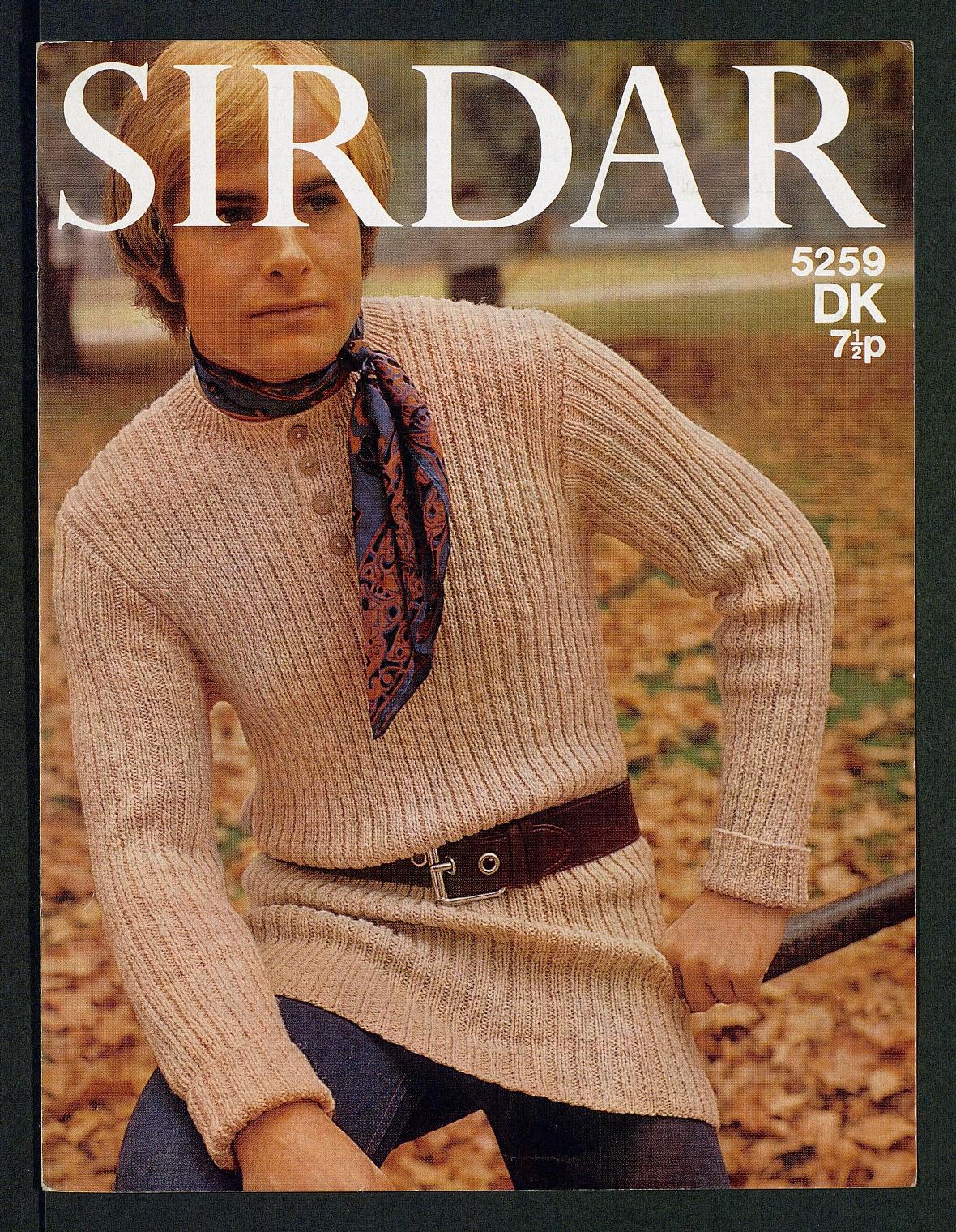

On an ordinary afternoon, a group of friends sit around listening to records. Someone puts on a Willie Nelson album, and there is a knock at the door. It’s an older man, making a delivery. He pauses behind his clipboard, hearing the music from inside the house. “Is that Red Headed Stranger,” he asks? Yes. He asks if he can come in and listen. And for the next thirty minutes, no one says a word as the album tells its mournful tale of betrayal and bloody revenge, a story, writes Allmusic “about a preacher on the run after murdering his departed wife and her new lover.” It’s an album that remains—with its “brief song-poems and utterly minimal backing”—perhaps “the strangest blockbuster country produced.”

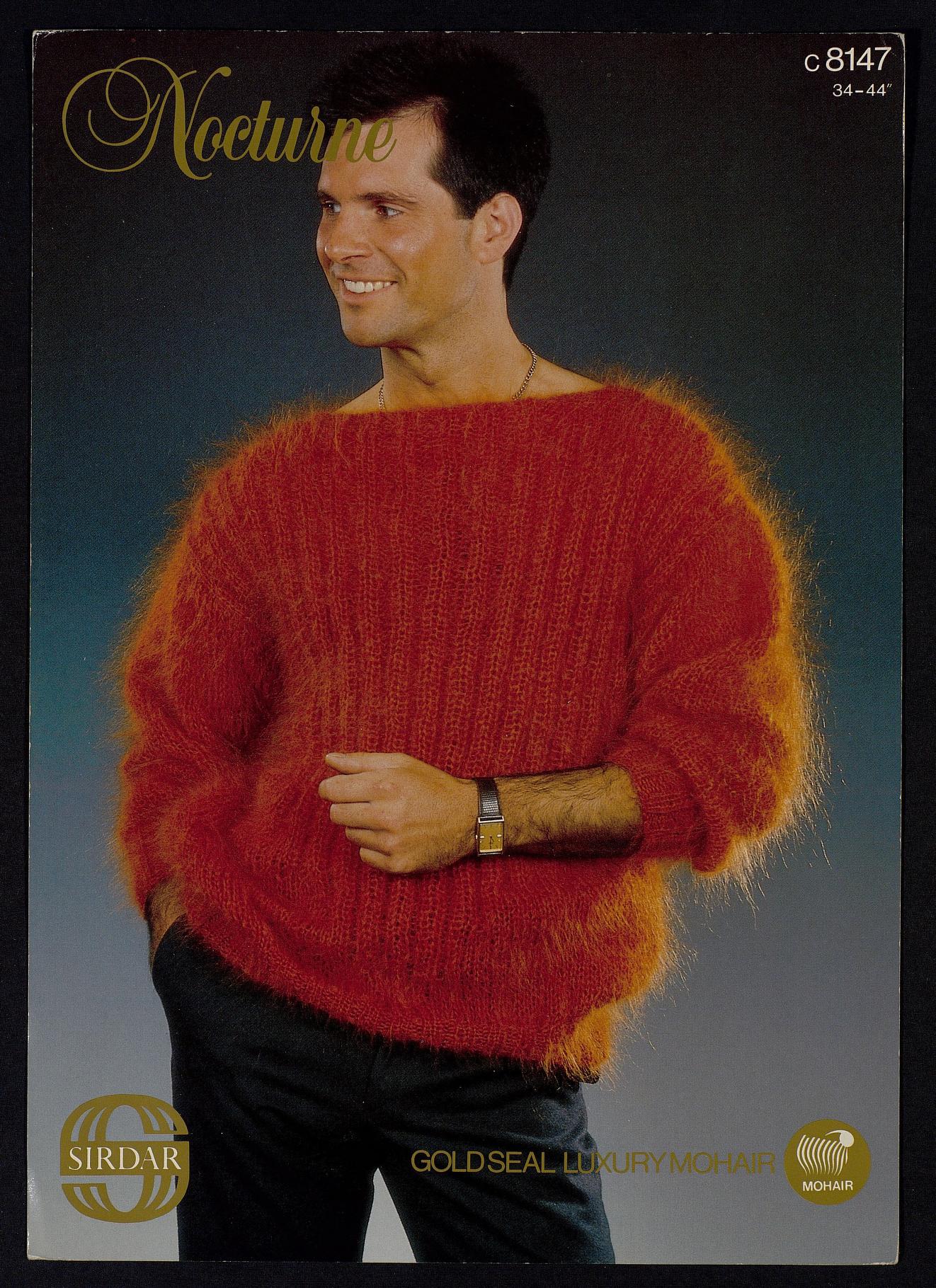

That 1975 album of tear-jerkers and murder ballads, which established Nelson as a “superstar recording artist,” is so “old-fashioned” it sounds “like a tale told around a cowboy campfire.” And it is for that reason millions of fans can’t tear themselves away from its compelling narrative and achingly sad, homespun laments—including myself, a few friends, and a stranger on a schedule who came to the door. And if Red Headed Stranger is an unlikely blockbuster, Nelson is an unlikely superstar, full of contradictions. He’s a gentle outlaw; an old-fashioned country troubadour who has remained on the progressive activist edge; and an unassuming, traditional artist who happens to be loved across the spectrum of generations, political persuasions, and musical styles.

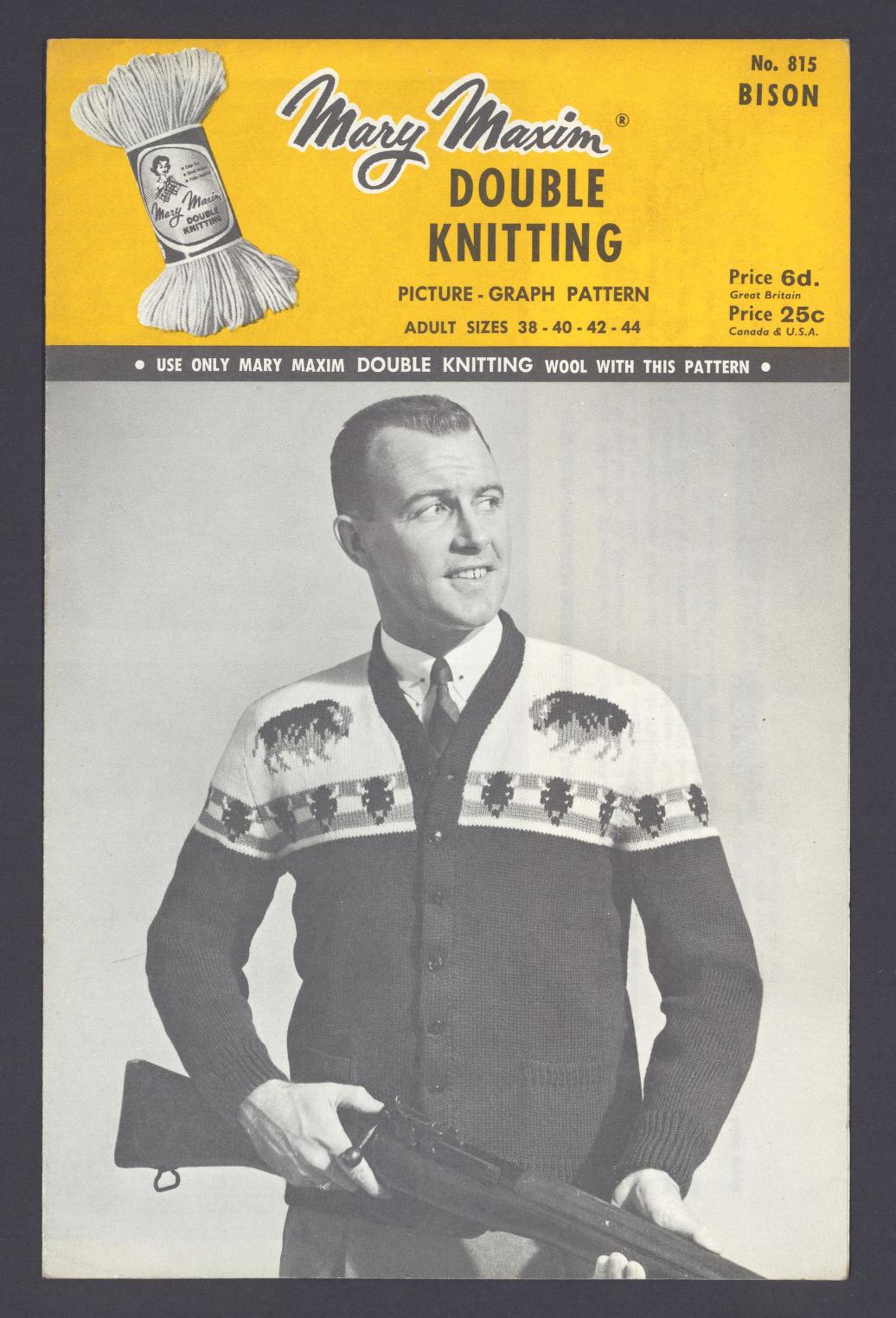

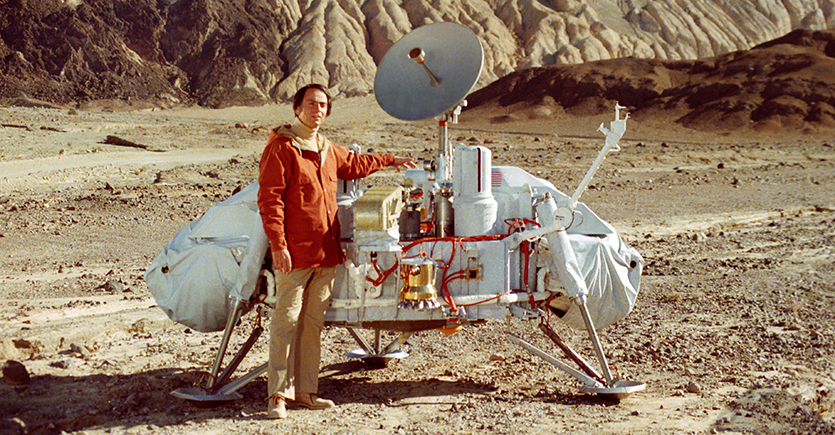

But before Nelson became an international superstar he appeared on the country music circuit clean-shaven, short-haired, and in the natty suit and tie you see him wear in the clip above from a televised 1962 Grand Ole Opry performance. Close your eyes and you’ll hear that it’s undoubtedly Nelson’s familiar warble—though not so weathered with age as we’ve grown used to. But when you look, it’s hard to see the grizzled tax-evading, pot-smoking outlaw hippie hero we know and love in this fresh-faced gent. Nelson had only just moved to Nashville two years prior, and he struggled to make an impression at first. But when country singer Faron Young heard him sing his “Hello Walls” at a bar next to the Opry, his fortunes changed. Young sent the song into the top 40, and Nelson became, as the host above calls him, “the Mickey Mantle of country music,” writing hit after hit.

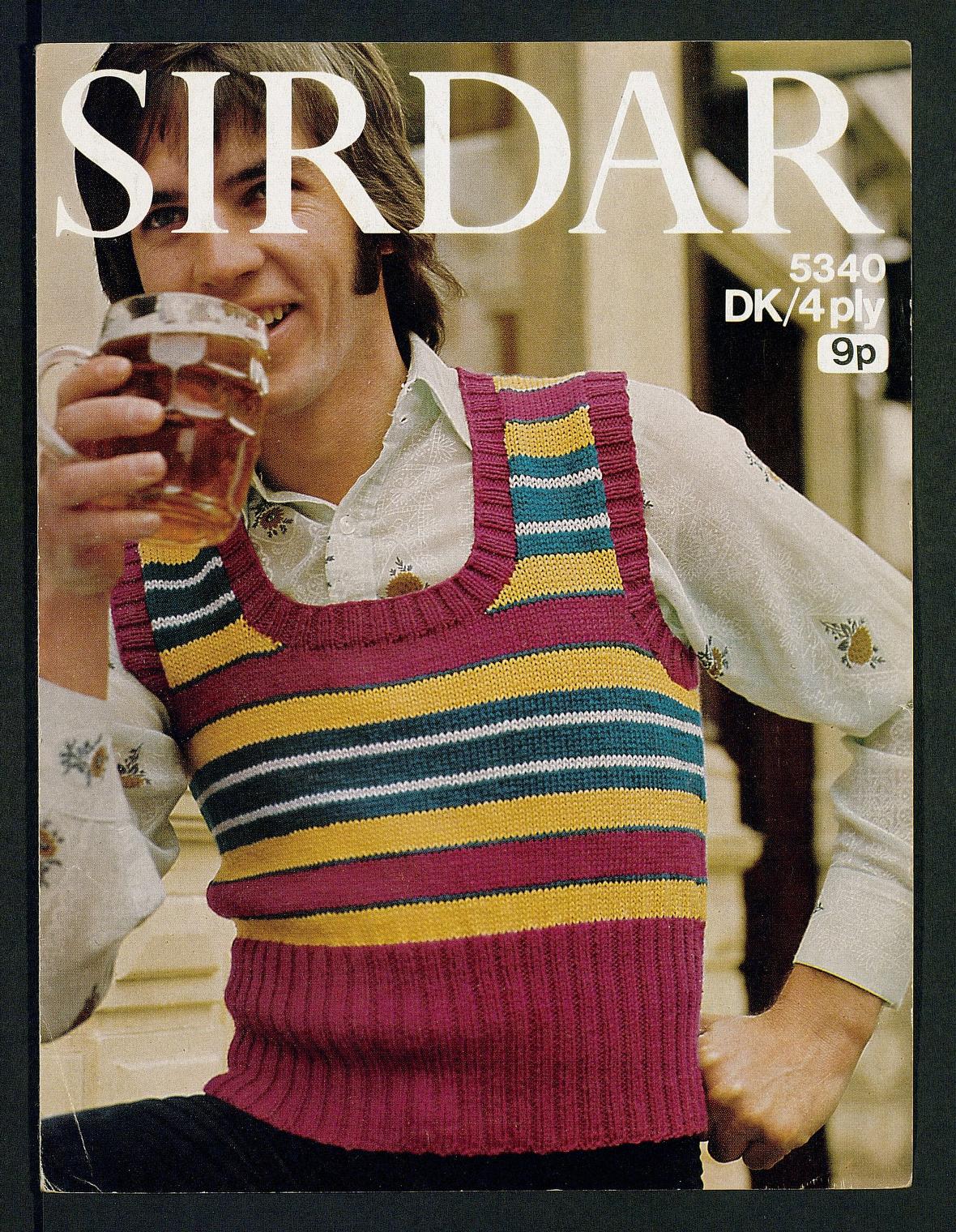

By ’62, he had recorded his first LP, And Then I Wrote, singing many songs he’d given to other artists. He opens above with “Hello Walls,” and he closes with his other massive hit from the period, “Crazy,” Patsy Cline’s signature tune. In-between, Nelson sings another song from his debut album, Billy Walker’s “Funny How Time Slips Away,” and works in “Night Life,” a blues song he wrote for Ray Price. Only eight years after this TV appearance, Nelson decided to retire from music and pack it in, feeling like his career had run its course. It wasn’t until a couple years later—after he’d become part of Austin’s eclectic music scene and re-invented himself musically with 1973’s Shotgun Willie—that the outlaw balladeer we know and love was born.

Related Content:

Willie Nelson Auditions for The Hobbit Film Sequel, Turns 80 Today

Johnny Cash: Singer, Outlaw, and, Briefly, Television Host

The 1969 Bob Dylan-Johnny Cash Sessions: 12 Rare Recordings

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness