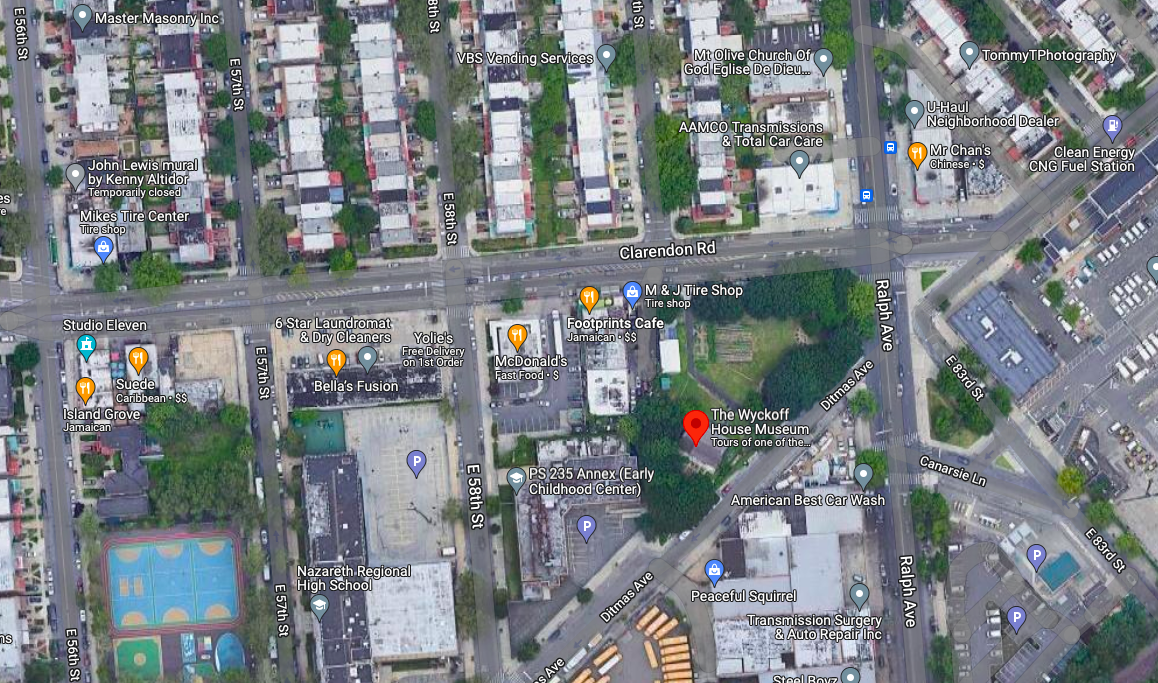

Most 21st-century Brooklyn public elementary schoolers have taken or will take a field trip to the Wyckoff House, a modest wooden cabin surrounded by tire shops and fast food outlets.

The oldest building in NYC by a longshot, it was also the first structure in the five boroughs to achieve historic landmark status.

Primary sources place the original occupants, Pieter Claesen Wyckoff and his wife, Grietje Van Ness-Wyckoff, in the original part of the house around 1652. A single room with a packed earth floor, unglazed windows, a large open hearth, and doors at either end, it would have been pretty tight quarters for a family of 13, as host Thijs Roes of the history series New Netherland Now notes, during his above tour of the premises.

Two parlors were added in the 18th-century, and three bedrooms in the early 19th. Typical Dutch Colonial features include an H frame structure, shingled walls, split Dutch doors, and deep, flared “spring” eaves.

Its survival is a miracle in a metropolis known for its constant flux.

In the early 20th-century, descendants of Pieter and Grietje partnered with community activists to save the home from demolition, eventually donating it to the New York City Parks Department.

A late 70s fire (possibly not the first) necessitated major renovations. (And last year, flooding from Hurricane Ida clobbered its HVAC and electrical system, putting a temporary kibosh on public visits to the interior.)

Back in 2015, Roes’ companion, architectural historian Heleen Westerhuijs, was invited to inspect the attic, where she discovered impressive original beams alongside 20th-century reinforcements.

While the directors of the homestead actively recognize the community that now surrounds it with events like an upcoming celebration of Haitian culture and Vodou, and hands on activities include urban farming and composting, the original settlers of New Netherland (aka New Amsterdam, aka New York City) remain a major focus.

Any American or Canadian with the surname Wyckoff (or one of its more than 50 variants) can and should consider it their ancestral home, as they are almost certainly descended from Pieter and Grietje. While many thousands now bear the name, Pieter was the first. Volunteer genealogist Lynn Wyckoff explains:

After the English assumed control of New Netherland, residents practicing patronymics (a naming system that utilized one’s father’s name in place of a surname) were required to adopt, or freeze, surnames that could be passed down each generation. Pieter Claesen chose the name Wykhof, which most of his descendants have spelled Wyckoff. Despite many unfounded claims over the years regarding both Pieter’s ancestry and choice of surname, there is no record of Pieter’s parentage; but there is substantial evidence that he chose the name Wykhof in recognition of a farm by the same name outside of Marienhafe, Germany where his family were likely tenants.

A handful of Wyckoff family members left comments on the New Netherland Now video, including Donald, who wrote of his visit:

It was an odd feeling to touch the hand-hewn surface of a supporting beam cut and installed by my ancestor, hundreds of years ago. Since I am a Wyckoff, I was allowed to see some of the “off tour” bits of the house. I live over 3k miles away, so my feet will probably never touch the ground there again. But I’m glad NY and a lot of wonderful people have maintained my ancestral home so well and for so many years. Hopefully it has many hundreds of years of life remaining so that people can recall a time when Flatbush was more of a farm than a city.

If you are a Wyckoff (or one of its variants), you’re invited to keep the Wyckoff Association’s family tree up to date by sending word of births, deaths, marriages, and any pertinent genealogical details such as education, military service, profession, places of residence and the like.

Explore a collection of educational activities, lessons, and color pages related to the Wyckoff House here.

Related Content

Immaculately Restored Film Lets You Revisit Life in New York City in 1911

New York City: A Social History (A Free Online Course from N.Y.U

- Ayun Halliday is the author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Her family’s trips to the Wyckoff House were included in the latest, NYC museum-themed issue of her zine, the East Village Inky. Follow her @AyunHalliday.