Ed Ruscha has lived nearly 65 years in Los Angeles, but he insists that he has no particular fascination with the place. Not everyone believes him: is disinterest among the many possible feelings that could motivate a painting like The Los Angeles County Museum on Fire? Nevertheless, the plainspoken Oklahoma-born artist has long stuck to his story, perhaps in order to let his often cryptic work speak for itself. Originally trained in commercial art, Ruscha has painted, printed, drawn, and taken photographs, the most celebrated fruit of that last pursuit being 1966’s Every Building on the Sunset Strip, a book that stitches his countless photographs of that famous boulevard — both sides of it — onto one long, continuous page.

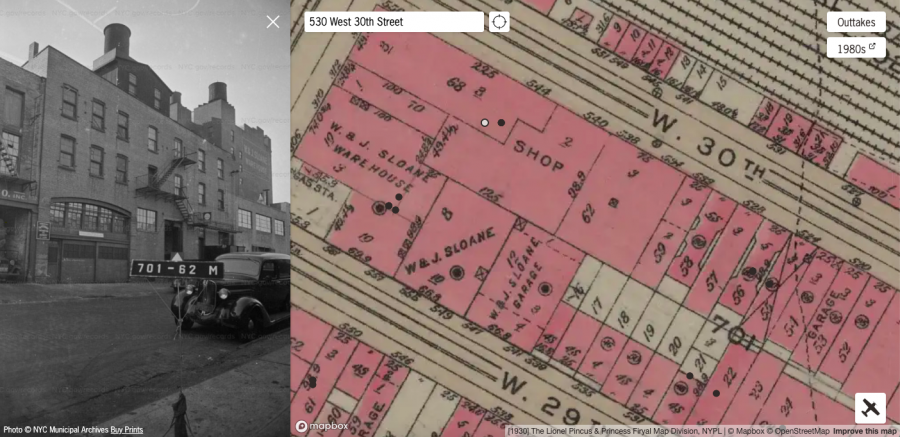

Whatever you think of such a project, you can’t accuse it of a mismatch between form and substance. Nor can you call it a cynical one-off: between 1967 and 2007, Ruscha drove Sunset Boulevard with his camera no fewer than twelve times in order to photograph most or all of its buildings.

These include gas stations (an architectural form to which Ruscha has made the subject of its own photo book as well as one of his most famous paintings), drugstores, appliance dealers, Central American restaurants, karate schools, travel agencies, car washes, Modernist office towers, and two of the most characteristic structures of Los Angeles: low-rise, kitschily named “dingbat” apartment blocks and L‑shaped “La Mancha” strip malls.

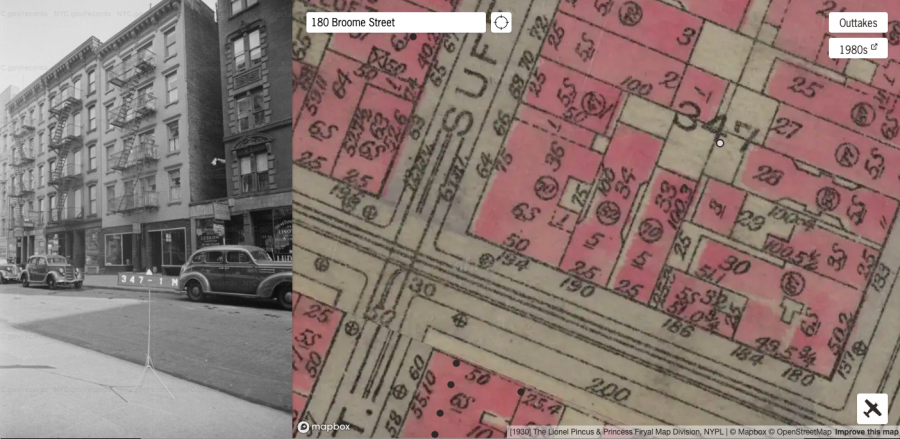

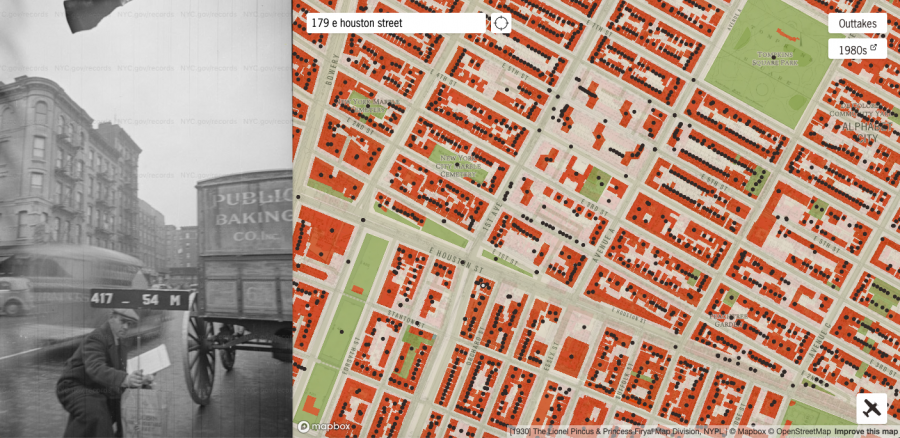

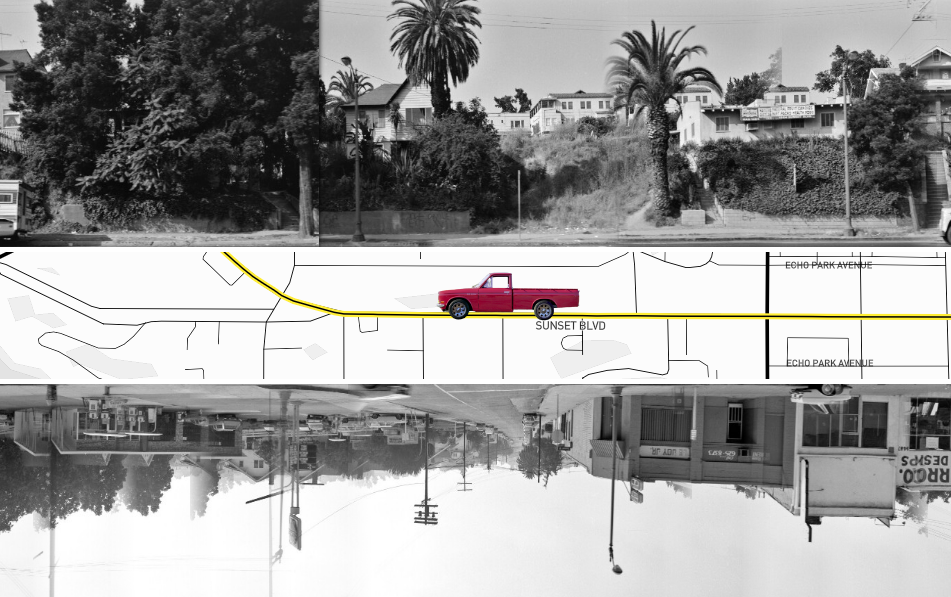

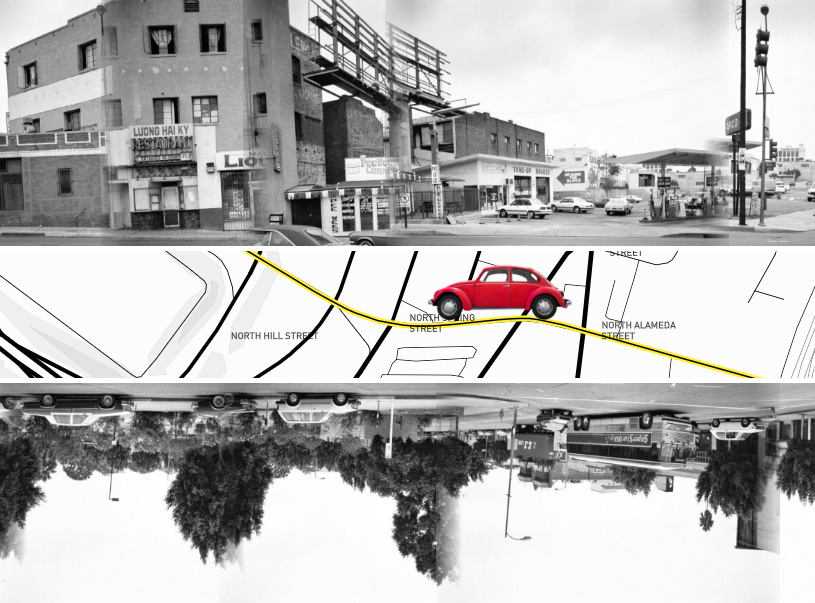

The mix of the built environment varies greatly, of course, depending on where you choose to go on this 22-mile-long boulevard, only a short stretch of which constitutes the “Sunset Strip.” It also depends on when you choose to go: not which time of day, but which era, a choice put at your fingertips by the Getty Research Institute’s Ed Ruscha Streets of Los Angeles Project, and specifically its interactive feature 12 Sunsets. In it you can use your left and right arrow keys to “drive” east or west (in your choice between a van, a VW Beetle, or Ruscha’s own trusty Datsun pickup), and your up and down button to flip between the year of the photo shoots that make up the boulevard around you.

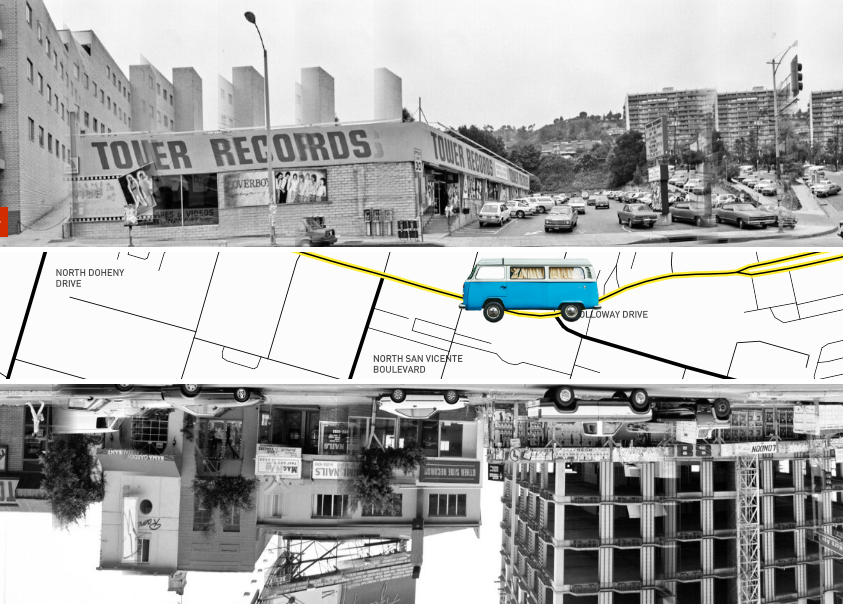

Many longtime Angelenos (or enthusiasts of Los Angeles culture) will motor straight to the intersection with Horn Avenue, location of the much-mythologized Sunset Strip Tower Records from which the very American musical zeitgeist once seemed to emanate. The Sacramento-founded store was actually a latecomer to Los Angeles compared to Ruscha himself, and the building first appears in his third photo shoot, of 1973. The next year the ever-changing posters on its exterior walls includes Billy Joel’s Piano Man. About a decade later appear the one-hit likes of Loverboy, and in the twilight of the 1990s the street elevation touts the Beastie Boys and Rob Zombie. In 2007, Tower’s signature red and yellow are all that remain, the chain itself having gone under (at least outside Japan) the year before.

12 Sunsets’ interface provides two different methods to get straight from one point to another: you can either type a specific place name into the “location search” box on the upper right, or click the map icon on the middle left to open up the line of the whole street clickable anywhere from downtown Los Angeles to the Pacific Ocean. This is a much easier way of making your way along Sunset Boulevard than actually driving it, even in the comparatively nonexistent traffic of 1965. Nevertheless, Ruscha continues to photographically document it and other Los Angeles streets, using the very same method he did 55 years ago. The buildings keep changing, but the city has never stopped exuding its characteristic normality so intensely as to become eccentricity (and vice versa). What artist worthy of the title wouldn’t be fascinated?

Explore the Getty Research Institute’s Ed Ruscha Streets of Los Angeles Project here.

Related Content:

Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol Demystify Their Pop Art in Vintage 1966 Film

A Brief History of John Baldessari, Narrated by Tom Waits

Take a Drive Through 1940s, 50s & 60s Los Angeles with Vintage Through-the-Car-Window Films

Watch Randy Newman’s Tour of Los Angeles’ Sunset Boulevard, and You’ll Love L.A. Too

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.