Maybe you, too, were a Latin geek who loved sword and sandal flicks from the golden age of the Hollywood epic? Quo Vadis, The Fall of the Roman Empire, The Robe, Demetrius and the Gladiators, and, of course, Spartacus…. Never mind all the heavy religious pretext, context, subtext, or hammer over the head that suffused these films, or any pretense toward historical accuracy. What thrilled me was seeing ancient Rome come alive, bustling with togas and tunics, centurions and chariots. The center of the ancient world for hundreds of years, the city, naturally, retains only traces of what it once was—enormous monuments that might as well be tombs.

The incredibly detailed 3D animations here don’t quite have the same rousing effect, granted, as the “I am Spartacus!” scene. They don’t star Charlton Heston, Sophia Loren, or Kirk Douglas. They appeal to different sensibilities, it’s true. But if you love the idea of visiting Rome during one of its peak periods, you might find them as satisfying, in their way, as Peter Ustinov’s Nero speeches.

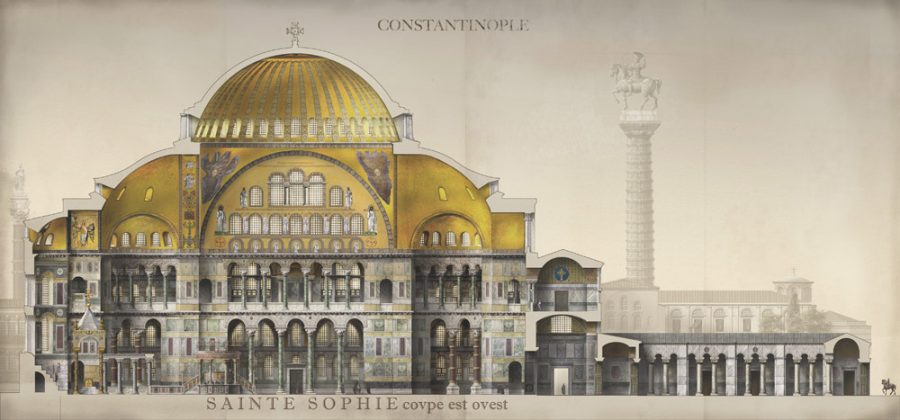

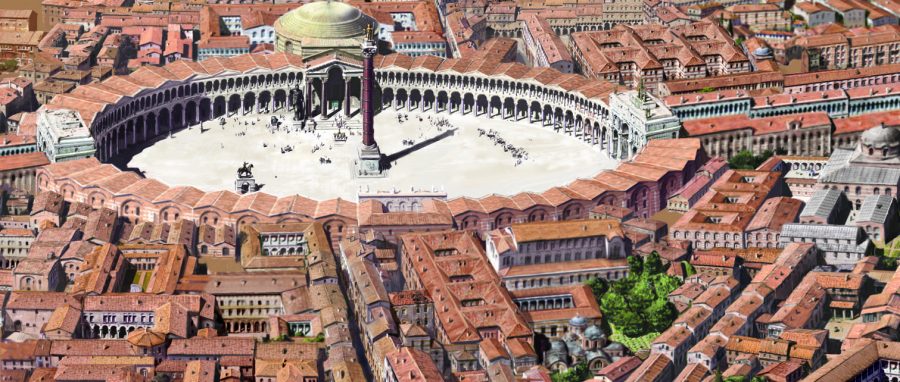

Dating not from the time of Mark Antony or even Jesus, the painstakingly-rendered tours of ancient Rome depict the city as it would have looked—sans humans and their activity—during its “architectural peak,” as Realm of History notes, under Constantine, “circa 320 AD.”

The VR trailer at the top from History in 3D, developed by Danila Loginov and Lasha Tskhondia, depicts, in Loginov’s words, “the Forums area, and also Palatine and Capitolium hills.” The two additional trailers for the project show the “baths of Trajan and Titus, the statue of Colossus Solis, arches of Titus and Constantine, Ludus Magnus, the temple of Divine Claudius. Our team spent some time and recreated this area along with all minor buildings as a complex and added it to the model which has been already done.” This means, he says, “we have now almost the entire center of ancient imperial Rome already recreated!”

We glide gently over the city with a low-flying-bird’s eye view, taking in its realistic skyline, tree-lined streets, and gurgling fountains. The lack of any human presence makes the experience a little chilly, but if you’re moved by classical architecture, it also presents a refreshing lack of distraction—an impossible request in a visit to modern Rome. Another project, Rome Reborn, which we’ve previously featured here, takes a different approach to the same imperial city of 320 AD. The trailers for their VR app don’t provide the seamless flight experience, but they do contain equally epic music. (They also have a few people in them, blockily-rendered gawking tourists rather than ancient Romans.)

Instead, these clips give us fascinating glimpses of the interiors of such splendid structures as the Basilica of Maxentius—tiled floors, domed ceilings, columned walls—from a number of different perspectives. We also get to fly above the city, drone-style, or hot air balloon-style, as it were. In the clip below, we cruise over Rome in that vehicle, with ****************@***il.com”>Bernard Frischer, professor emeritus at the University of Virginia, serving as the app’s “virtual archaeologist” in an audio tour.

“The ambitious undertaking,” of the Rome Reborn app, writes Meilan Solly at Smithsonian, “painstakingly built by a team of 50 academics and computer experts over a 22-year period, recreates 7,000 buildings and monuments scattered across a 5.5 square mile stretch of the famed Italian city.” The three modules of the Rome Reborn app demoed here are all available at their website. Geeks—and historians of ancient Roman architecture and city planning—rejoice.

via Smithsonian

Related Content:

A Huge Scale Model Showing Ancient Rome at Its Architectural Peak (Built Between 1933 and 1937)

An Interactive Map Shows Just How Many Roads Actually Lead to Rome

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness