Much in Ukraine has been lost since the Russian invasion commenced this past February. But efforts to minimize the damage have been responding on all fronts, and not just geographical ones. The preservation of Ukrainian culture has become the top priority for some groups, in response to Russian forces’ seeming intent to destroy it. “Cultural heritage is not only impacted, but in many ways it’s implicated in and central to armed conflict,” says Hayden Bassett, director of the Virginia Museum of Natural History’s Cultural Heritage Monitoring Lab, in the Vox explainer above. “These are things that people point to that are unifying factors for their society. They are tangible reflections of their society.”

This very quality made them a sadly appealing target for Russian attacks. As the video’s narrator puts it, Vladimir Putin “has made it clear that identity is at the ideological center of Russia’s invasion,” ostensibly an effort to reunify two lands of a common civilization. For Ukraine, the strategy to protect its own cultural heritage during wartime involves two phases of work.

First, “identify what needs protecting,” already a requirement of the 1954 Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict (known as the “Hague Convention). In Ukraine’s case, the list includes no fewer than seven UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

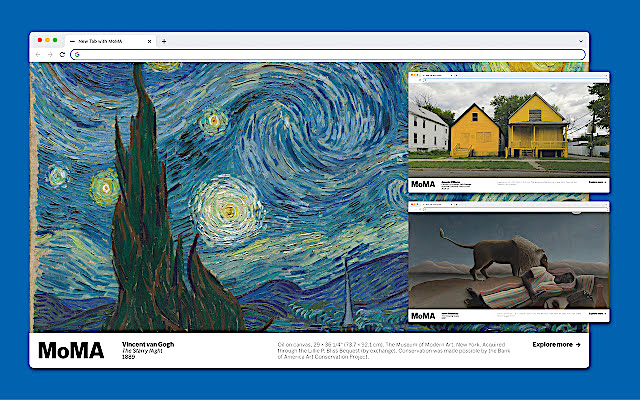

Step two is to secure these cultural treasures, whether they be paintings, sculptures, buildings, or anything else besides. This requires the collaboration of “government agencies, militaries, NGOs, academics, museum institutions,” says Bassett, as well as of volunteers on the ground physically safeguarding the artifacts. This often involves hiding them whenever possible, and “if history is any indication,” says the narrator, “collections have moved underground or outside of major cities, or outside the country entirely.” So it was in Europe under the marauding of Nazi Germany, including, as seen in the France 24 segment above, with holdings of the Louvre up to and including the Mona Lisa. The state of world geopolitics today may have us wondering if we’ve truly learned the lessons of the Second World War, but at least the fight to save Ukrainian culture reminds that we haven’t forgotten them all.

Related content:

Take a Virtual Reality Tour of the World’s Stolen Art

Ukrainians Playing Violin in Bunkers as Russians Bomb Them from the Sky

When Pablo Picasso and Guillaume Apollinaire Were Accused of Stealing the Mona Lisa (1911)

Why Russia Invaded Ukraine: A Useful Primer

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.