They wouldn’t have let Jean-Michel into a Tiffany’s if he wanted to use the bathroom or if he went to buy an engagement ring and pulled a wad of cash out of his pocket.

– Stephen Torton, Jean-Michel Basquiat’s studio assistant

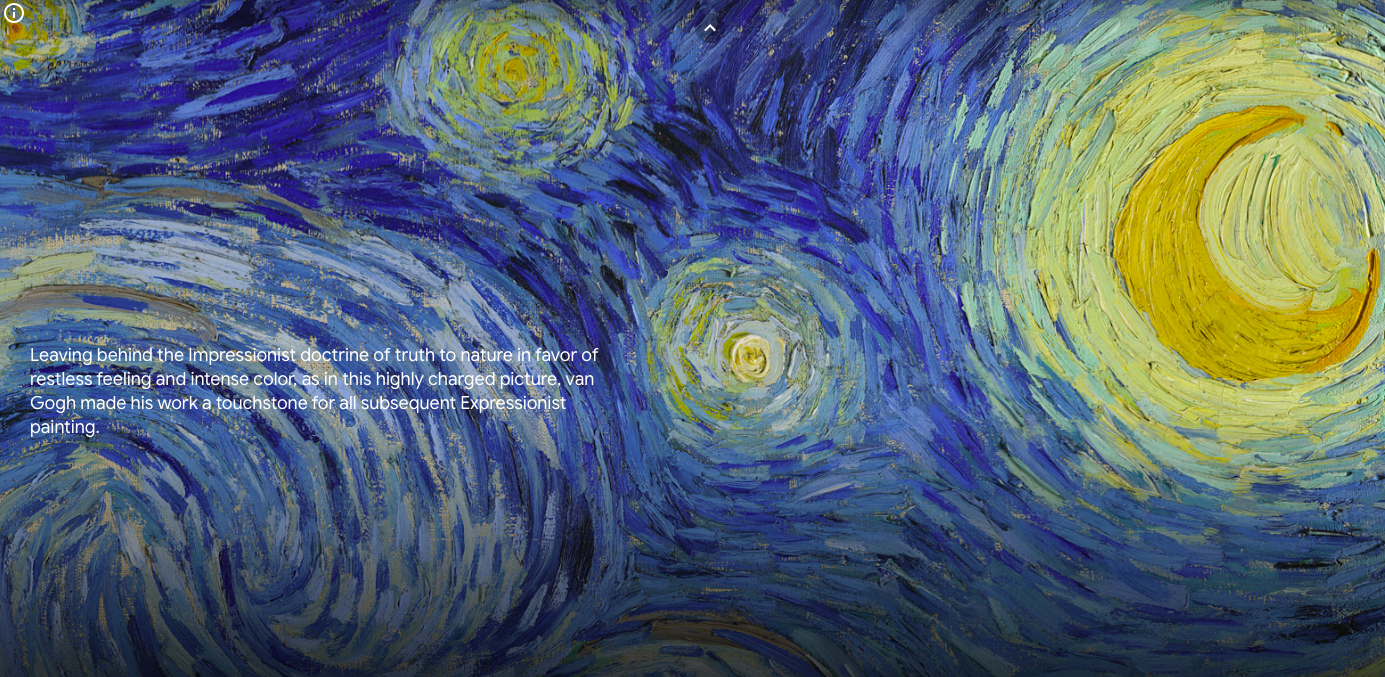

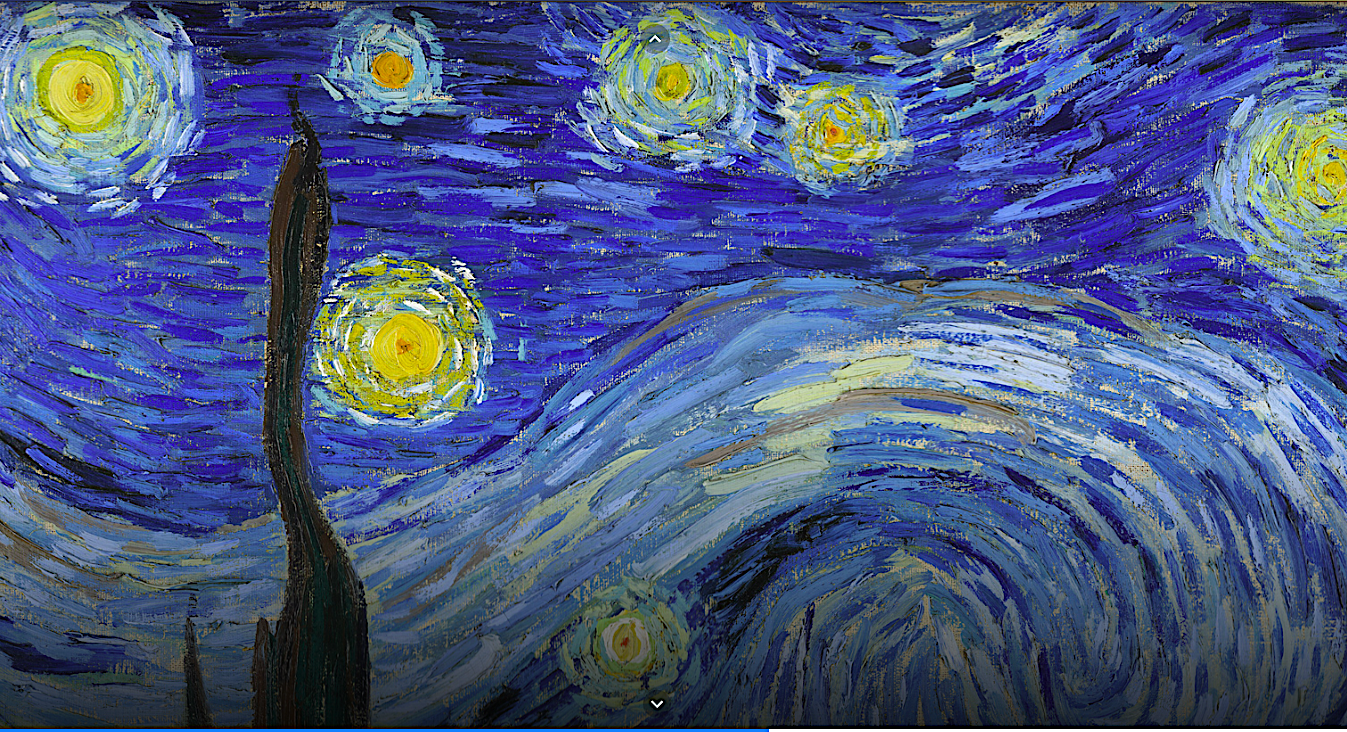

When Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Untitled (Skull) sold for $110.5 million in 2017 to Japanese billionaire Yusaku Maesawa, the artist joined the ranks of Da Vinci, De Kooning, and Picasso as one of the top selling painters in the world, surpassing a previous record set in 2013 by his mentor Andy Warhol’s work. Untitled dates from 1982, during “the young Basquiat’s mercurial early years,” writes Ben Davis at Artnet, “even before his first gallery show at Annina Nosei, when he was still a Caribbean-American kid from Brooklyn energetically bootstrapping himself into the limelight of the downtown art scene.” It is this period that most interests collectors like Maesawa.

Basquiat’s transition from graffiti artist to art world darling was dramatic, celebratory, and self-destructive, all characteristics of his work. But critical primitivism reduced him to a token — an art world attitude saw Basquiats as objects to be stripped of context, turned into decorative badges of authenticity and worldliness. “Maezawa’s head painting possesses a loud, gnashing, and confident aura,” Shannon Lee writes at Artsy. But the artist’s “use of skulls… is deeply rooted in his identity as a Black artist in America. They are strongly evocative of African masks, which have been so fetishized by the art market since modernists like Picasso appropriated them from their native contexts.”

But head/skull motifs in Basquiat’s work are not only statements of diasporic Black identity — they emerge through his thematic play of human embodiment, mental illness/health, the competitions of the graffiti world and the headgames of the art world, which Basquiat both mastered and critiqued as a canny outsider. “No subject is more powerful or more sought after in the oeuvre of Jean-Michel Basquiat,” notes Christie’s New York, “than the singular skull.” Though maybe not the most reproduced of Basquiat’s heads, 1982’s Untitled — argues the Great Art Explained video above — exemplifies the themes.

At only 22 years old, Basquiat produced “a single painting” that said “everything he wanted to say about America, about art and about being black in both worlds.” So singular is Untitled that it became its own one-painting show in 2018 when its new owner sent it on a tour of the world, beginning in the artist’s hometown at the Brooklyn Museum. Maesawa’s decision to share the painting presents a contrast to the way Basquiat has been treated differently by other owners of his work like Tiffany & Co., who explain their purchase and recent, controversial commercial use of his Equals Pi by citing his “affinity for the company’s statement blue color,” writes Tirhakah Love at Daily Beast — a color they trademarked ten years after Basquiat’s death.

The proprietary co-optation of Basquiat’s life and work to sell symbols of colonialism like diamonds, among other luxury goods — and the turning of his work into the ultimate luxury good — debases his purposes. Why show Equals Pi “as a prop to an ad?” asked his friend and former roommate Alexis Adler. “Loan it out to a museum. In a time where there were very few Black artists represented in Western museums, that was his goal: to get to a museum.” Find out in the Great Art Explained video how one of his most famous — and most expensive — works encapsulates that struggle through its vivid color and symbolic visual language.

Related Content:

The Story of Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Rise in the 1980s Art World Gets Told in a New Graphic Novel

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness