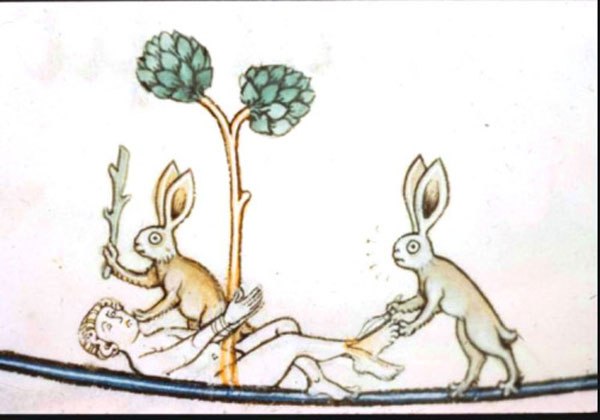

In all the kingdom of nature, does any creature threaten us less than the gentle rabbit? Though the question may sound entirely rhetorical today, our medieval ancestors took it more seriously — especially if they could read illuminated manuscripts, and even more so if they drew in the margins of those manuscripts themselves. “Often, in medieval manuscripts’ marginalia we find odd images with all sorts of monsters, half man-beasts, monkeys, and more,” writes Sexy Codicology’s Marjolein de Vos. “Even in religious books the margins sometimes have drawings that simply are making fun of monks, nuns and bishops.” And then there are the killer bunnies.

Hunting scenes, de Vos adds, also commonly appear in medieval marginalia, and “this usually means that the bunny is the hunted; however, as we discovered, often the illuminators decided to change the roles around.”

Jon Kaneko-James explains further: “The usual imagery of the rabbit in Medieval art is that of purity and helplessness – that’s why some Medieval portrayals of Christ have marginal art portraying a veritable petting zoo of innocent, nonviolent, little white and brown bunnies going about their business in a field.” But the creators of this particular type of humorous marginalia, known as drollery, saw things differently.

“Drolleries sometimes also depicted comedic scenes, like a barber with a wooden leg (which, for reasons that escape me, was the height of medieval comedy) or a man sawing a branch out from under himself,” writes Kaneko-James.

This enjoyment of the “world turned upside down” produced the drollery genre of “the rabbit’s revenge,” one “often used to show the cowardice or stupidity of the person illustrated. We see this in the Middle English nickname Stickhare, a name for cowards” — and in all the drawings of “tough hunters cowering in the face of rabbits with big sticks.”

Then, of course, we have the bunnies making their attacks while mounted on snails, snail combats being “another popular staple of Drolleries, with groups of peasants seen fighting snails with sticks, or saddling them and attempting to ride them.”

Given how often we denizens of the 21st century have trouble getting humor from less than a century ago, it feels satisfying indeed to laugh just as hard at these drolleries as our medieval forebears must have — though many more of us surely get to see them today, circulating as rapidly on social media as they didn’t when confined to the pages of illuminated manuscripts owned only by wealthy individuals and institutions.

You can see more marginal scenes of the rabbit’s revenge at Sexy Codicology, Colossal, and Kaneko-James’ blog. But one historical question remains unanswered: to what extent did they influence that pillar of modern cinematic comedy, Monty Python and the Holy Grail?

Related Content:

Explosive Cats Imagined in a Strange, 16th Century Military Manual

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.