Revisiting Ernest Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast a couple of decades after I read it last, I notice a few things right away: I am still moved by the prose and think it’s as impressive as ever; I am less moved by the machismo and alcoholism and more interested in characters like Sylvia Beach, founder of Shakespeare and Company, the bookstore that served as a base of operations for the famed Lost Generation of writers in Paris.

“Sylvia had a lively, sharply sculptured face, brown eyes that were as alive as a small animal’s and as gay as a young girl’s,” Hemingway wrote of her in his memoir. “She was kind, cheerful and interested, and loved to make jokes and gossip. No one that I ever knew was nicer to me.” Indeed, Hemingway also “recounts being given access to the whole of Sylvia Beach’s library at Shakespeare and Company for free after his first visit,” notes writer RJ Smith.

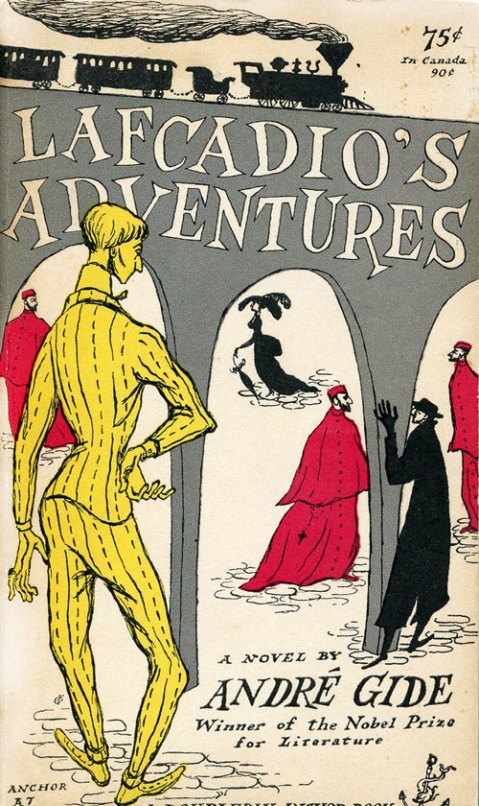

Beach founded the shop in 1919, encouraged (and funded) by her partner Adrienne Monnier, who owned a French-language bookstore. Beach’s mostly English-language Shakespeare and Company would become a lending-library, post office, bank, and even hotel for authors who congregated there. She supported the great expatriate modernists and hosted French writers like André Gide and Paul Valéry. She also published James Joyce’s Ulysses in 1922 when no one else would, after earlier published excerpts were deemed “obscene.”

Joyce was shaped by Paris, and owed a huge debt of gratitude to Beach, just as readers of Ulysses do almost 100 years later. Forty years after the novel’s publication, Beach traveled to Ireland to celebrate and sat down for the long interview above in which she remembers those heady times. She also tells the story of how a Presbyterian minister’s daughter—who went to church in Princeton, NJ with Grover Cleveland and Woodrow Wilson—became a pioneering out lesbian modernist bookseller in Paris.

Beach remembers meeting “all the French writers” at Monnier’s shop after her time studying at the Sorbonne and how American writers all came to Paris to escape prohibition at home. “For Hemingway and his most of his friends,” says Harvard historian Patrice Higonnet, “Paris was one long binge, all the more enjoyable because it wasn’t very expensive.” For Beach, Paris became home, and Shakespeare and Company a home away from home for waves of expats until the Nazis shut it down in 1941. (Ten years later, a different Shakespeare and Company was opened by bookseller George Whitman.)

“They were disgusted in America because they couldn’t get a drink,” Beach says, “and they couldn’t get Ulysses. I used to think those were the two great causes of their discontent.” Her interviews, letters, and her own memoir, Shakespeare and Company, tell the story of the Lost Generation from her point of view, one animated by an absolute devotion to literature, and in particular, to Joyce, who did not reciprocate. When Ulysses sold to Random House in 1932, he offered her no share of his very large advance.

Beach was forgiving. “I understood from the first,” she said, “that working with or for Mr. Joyce, the pleasure was mine—an infinite pleasure: the profits were for him.” She was doing something other than running a business. She was “cross-fertilizing,” as French writer Andre Chamson put it. “She did more to link England, the United States, Ireland, and France than four great ambassadors combined.” She did so by giving writers what they needed to make the work she knew they could, at a very rare time and place in which such a thing was briefly possible.

Related Content:

Beginnings Profiles Shakespeare and Company’s Sylvia Beach Whitman

F. Scott Fitzgerald Has a Strange Dinner with James Joyce & Draws a Cute Sketch of It (1928)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness