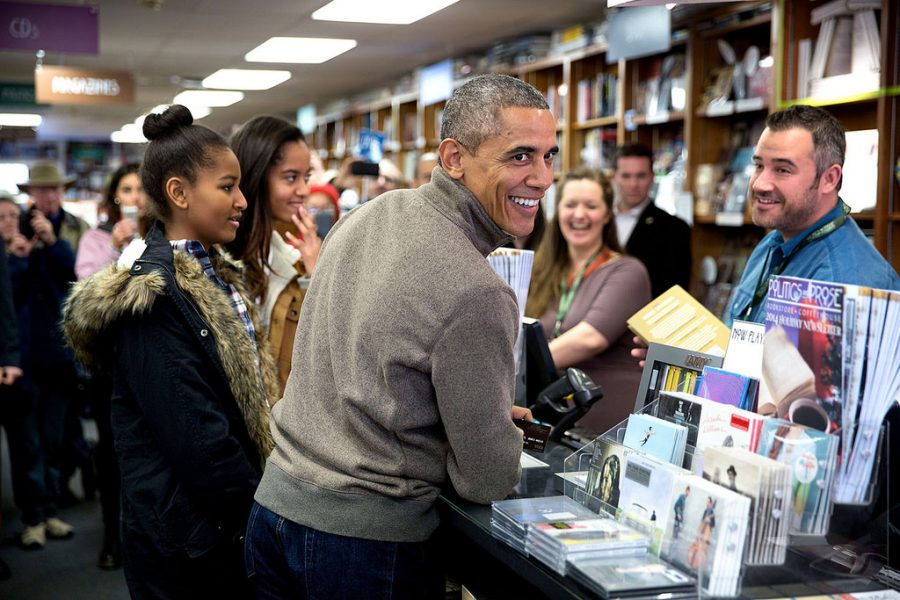

Photo by Pete Souza via obamawhitehouse.archive.gov

Whatever historians have to say about his political legacy, Barack Obama will be remembered as charming, diplomatic, thoughtful, and very well-read. He honed these personal qualities not only as a politician but as a scholar, writer, and teacher, roles that require intellectual curiosity and openness to other points of view. The former president was something of a dream come true for teachers and librarians, who could point to him as a shining example of a world leader who loves to read, talk about books, and share books with others. All kinds of books: from novels and poetry to biography, philosophy, sociology, and political and scientific nonfiction; books for children and books for young adults.

It is refreshing to look back at his tenure as a reliable recommender of quality books during his eight years in office. (See every book he recommended during his two terms here.) Reading gave him the ability to “slow down and get perspective,” he told Michiko Kakutani last year. He hoped to use his office, he said, “to widen the audience for good books. At a time when so much of our politics is trying to manage this clash of cultures brought about by globalization and technology and migration, the role of stories to unify—as opposed to divide, to engage rather than to marginalize—is more important than ever.”

While many people have been hoping he would weigh in on deeply disturbing current events, he “has been relatively quiet on social media of late,” notes Thu-Huong Ha at Quartz. But he has continued to use his platform to recommend good books, suggesting that the perspectives we gain from reading are as critical as ever. “In a Facebook post published on Saturday, Obama recommended some of the nonfiction he’s read recently, focused on government, inequality, and history, with one book that addresses immigration. Together the recommendations are an intellectual antidote to the current US president, who eschews reading,” says Ha.

The list below includes Obama’s brief commentary on each book and article.

Futureface: A Family Mystery, an Epic Quest, and the Secret to Belonging, by Alex Wagner (2018)

Journalist Alex Wagner investigates a potential new twist in her family’s history. “What she came up with,” Obama writes, “is a thoughtful, beautiful meditation on what makes us who we are—the search for harmony between our own individual identities and the values and ideals that bind us together as Americans.”

The New Geography of Jobs, by Enrico Moretti (2012)

Economist Enrico Moretti argues that there are three Americas: brain-hub cities like Austin and Boston; cities once dominated by traditional manufacturing; and the cities in between. “Still a timely and smart discussion of how different cities and regions have made a changing economy work for them,” writes Obama, “and how policymakers can learn from that to lift the circumstances of working Americans everywhere.”

Why Liberalism Failed, by Patrick J. Deneen (2018)

Political scientist Patrick J. Deneen argues that liberalism is not the result of the natural state of politics and lays out the ideology’s inherent contradictions. “In a time of growing inequality, accelerating change, and increasing disillusionment with the liberal democratic order we’ve known for the past few centuries,” says the former president, “I found this book thought-provoking.”

“The 9.9 Percent Is the New American Aristocracy,” by Matthew Stewart (June 2018)

In The Atlantic, Matthew Stewart, author of The Management Myth, defines a “cognitive elite,” a “9.9%” of Americans who value meritocracy and, he argues, are complicit in the erosion of democracy. “Another thought-provoking analysis, this one about how economic inequality in America isn’t just growing, but self-reinforcing,” says Obama.

In the Shadow of Statues: A White Southerner Confronts History, by Mitch Landrieu (2018)

Mitch Landrieu, the former mayor of New Orleans, Louisiana, writes in his memoir of the personal history and reckoning with race that led him to take down four Confederate statues in 2017. “It’s an ultimately optimistic take from someone who believes the South will rise again not by reasserting the past, but by transcending it,” writes Obama.

“Truth Decay: An Initial Exploration of the Diminishing Role of Facts and Analysis in American Public Life,” by Jennifer Kavanagh and Michael D. Rich, RAND Corporation (2018)

This report for the nonprofit RAND Corporation, available as a free ebook, attempts to study the erosion of fact-based policy making and discourse in the US. “A look at how a selective sorting of facts and evidence isn’t just dishonest, but self-defeating,” says Obama.

While the former president no longer has the power to sway policy, he can still inspire millions of people to read—essential for staying balanced, informed, and reflective in our perilous times.

Related Content:

The 5 Books on President Obama’s 2016 Summer Reading List

The Obama “Hope” Poster & The New Copyright Controversy

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness