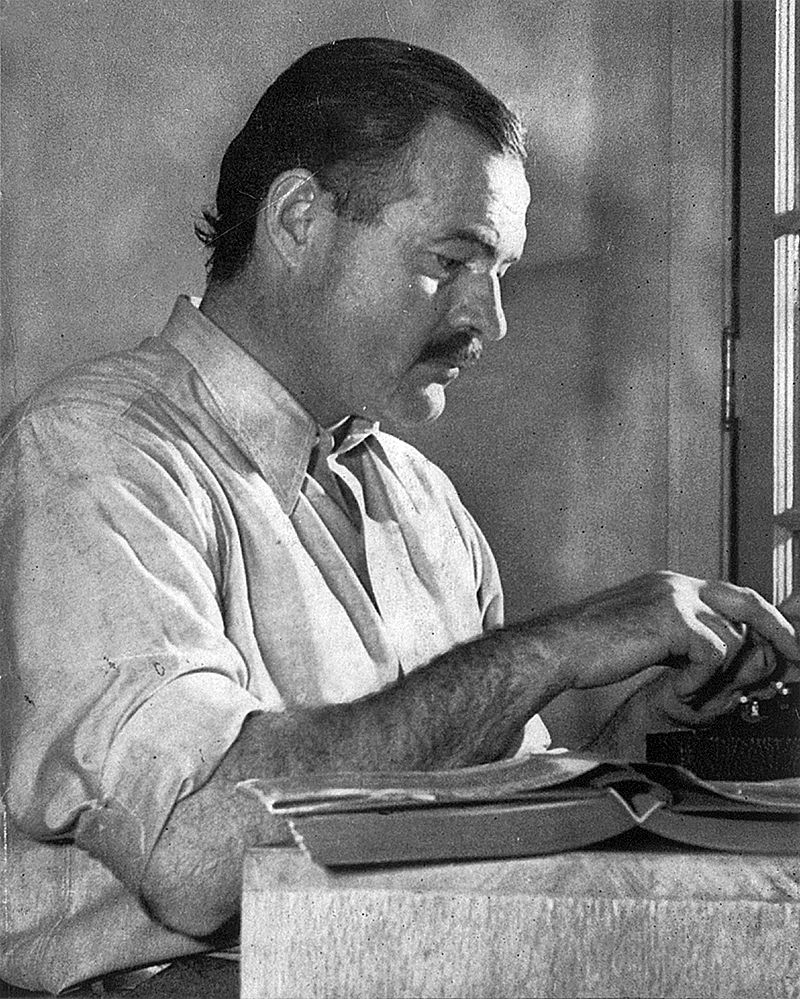

Image by Lloyd Arnold via Wikimedia Commons

Before he was a big game hunter, before he was a deep-sea fisherman, Ernest Hemingway was a craftsman who would rise very early in the morning and write. His best stories are masterpieces of the modern era, and his prose style is one of the most influential of the 20th century.

Hemingway never wrote a treatise on the art of writing fiction. He did, however, leave behind a great many passages in letters, articles and books with opinions and advice on writing. Some of the best of those were assembled in 1984 by Larry W. Phillips into a book, Ernest Hemingway on Writing. We’ve selected seven of our favorite quotations from the book and placed them, along with our own commentary, on this page. We hope you will all–writers and readers alike–find them fascinating.

1: To get started, write one true sentence.

Hemingway had a simple trick for overcoming writer’s block. In a memorable passage in A Moveable Feast, he writes:

Sometimes when I was starting a new story and I could not get it going, I would sit in front of the fire and squeeze the peel of the little oranges into the edge of the flame and watch the sputter of blue that they made. I would stand and look out over the roofs of Paris and think, “Do not worry. You have always written before and you will write now. All you have to do is write one true sentence. Write the truest sentence that you know.” So finally I would write one true sentence, and then go on from there. It was easy then because there was always one true sentence that I knew or had seen or had heard someone say. If I started to write elaborately, or like someone introducing or presenting something, I found that I could cut that scrollwork or ornament out and throw it away and start with the first true simple declarative sentence I had written.

2: Always stop for the day while you still know what will happen next.

There is a difference between stopping and foundering. To make steady progress, having a daily word-count quota was far less important to Hemingway than making sure he never emptied the well of his imagination. In an October 1935 article in Esquire ( “Monologue to the Maestro: A High Seas Letter”) Hemingway offers this advice to a young writer:

The best way is always to stop when you are going good and when you know what will happen next. If you do that every day when you are writing a novel you will never be stuck. That is the most valuable thing I can tell you so try to remember it.

3: Never think about the story when you’re not working.

Building on his previous advice, Hemingway says never to think about a story you are working on before you begin again the next day. “That way your subconscious will work on it all the time,” he writes in the Esquire piece. “But if you think about it consciously or worry about it you will kill it and your brain will be tired before you start.” He goes into more detail in A Moveable Feast:

When I was writing, it was necessary for me to read after I had written. If you kept thinking about it, you would lose the thing you were writing before you could go on with it the next day. It was necessary to get exercise, to be tired in the body, and it was very good to make love with whom you loved. That was better than anything. But afterwards, when you were empty, it was necessary to read in order not to think or worry about your work until you could do it again. I had learned already never to empty the well of my writing, but always to stop when there was still something there in the deep part of the well, and let it refill at night from the springs that fed it.

4: When it’s time to work again, always start by reading what you’ve written so far.

T0 maintain continuity, Hemingway made a habit of reading over what he had already written before going further. In the 1935 Esquire article, he writes:

The best way is to read it all every day from the start, correcting as you go along, then go on from where you stopped the day before. When it gets so long that you can’t do this every day read back two or three chapters each day; then each week read it all from the start. That’s how you make it all of one piece.

5: Don’t describe an emotion–make it.

Close observation of life is critical to good writing, said Hemingway. The key is to not only watch and listen closely to external events, but to also notice any emotion stirred in you by the events and then trace back and identify precisely what it was that caused the emotion. If you can identify the concrete action or sensation that caused the emotion and present it accurately and fully rounded in your story, your readers should feel the same emotion. In Death in the Afternoon, Hemingway writes about his early struggle to master this:

I was trying to write then and I found the greatest difficulty, aside from knowing truly what you really felt, rather than what you were supposed to feel, and had been taught to feel, was to put down what really happened in action; what the actual things were which produced the emotion that you experienced. In writing for a newspaper you told what happened and, with one trick and another, you communicated the emotion aided by the element of timeliness which gives a certain emotion to any account of something that has happened on that day; but the real thing, the sequence of motion and fact which made the emotion and which would be as valid in a year or in ten years or, with luck and if you stated it purely enough, always, was beyond me and I was working very hard to get it.

6: Use a pencil.

Hemingway often used a typewriter when composing letters or magazine pieces, but for serious work he preferred a pencil. In the Esquire article (which shows signs of having been written on a typewriter) Hemingway says:

When you start to write you get all the kick and the reader gets none. So you might as well use a typewriter because it is that much easier and you enjoy it that much more. After you learn to write your whole object is to convey everything, every sensation, sight, feeling, place and emotion to the reader. To do this you have to work over what you write. If you write with a pencil you get three different sights at it to see if the reader is getting what you want him to. First when you read it over; then when it is typed you get another chance to improve it, and again in the proof. Writing it first in pencil gives you one-third more chance to improve it. That is .333 which is a damned good average for a hitter. It also keeps it fluid longer so you can better it easier.

7: Be Brief.

Hemingway was contemptuous of writers who, as he put it, “never learned how to say no to a typewriter.” In a 1945 letter to his editor, Maxwell Perkins, Hemingway writes:

It wasn’t by accident that the Gettysburg address was so short. The laws of prose writing are as immutable as those of flight, of mathematics, of physics.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related content:

Writing Tips by Henry Miller, Elmore Leonard, Margaret Atwood, Neil Gaiman & George Orwell

The Big Ernest Hemingway Photo Gallery: The Novelist in Cuba, Spain, Africa and Beyond

The Spanish Earth, Written and Narrated by Ernest Hemingway

Archive of Hemingway’s Newspaper Reporting Reveals Novelist in the Making

Find Courses on Hemingway and Other Authors in our big list of Free Online Courses