Pop culture thrives on superheroes, both fictional and real. This isn’t unique in human history. Read most any collection of ancient myth and literature and you’ll find the same. The demigods and chieftains beating their chests and talking trash in the Iliad, for example, remind me of macho professional wrestlers or characters in the Marvel and DC universes, cultural artifacts indebted in their various ways to classical legends. One thread runs through all of the epic tales of heroes and heroines: a seeming need to immortalize people who embody the qualities we most desire. Heroes may suffer for their tragic flaws, but that’s the price they pay for universal acclaim or an iron throne.

The traits ascribed to late modernity’s fictional heroes haven’t changed overmuch from the distant past—power, wit, agility, persistence, anger issues, spicy, complicated love lives…. But when it comes to the real people we admire—the celebrities who get the superhero treatment—creativity, style, and musical talent top the list. Why not?

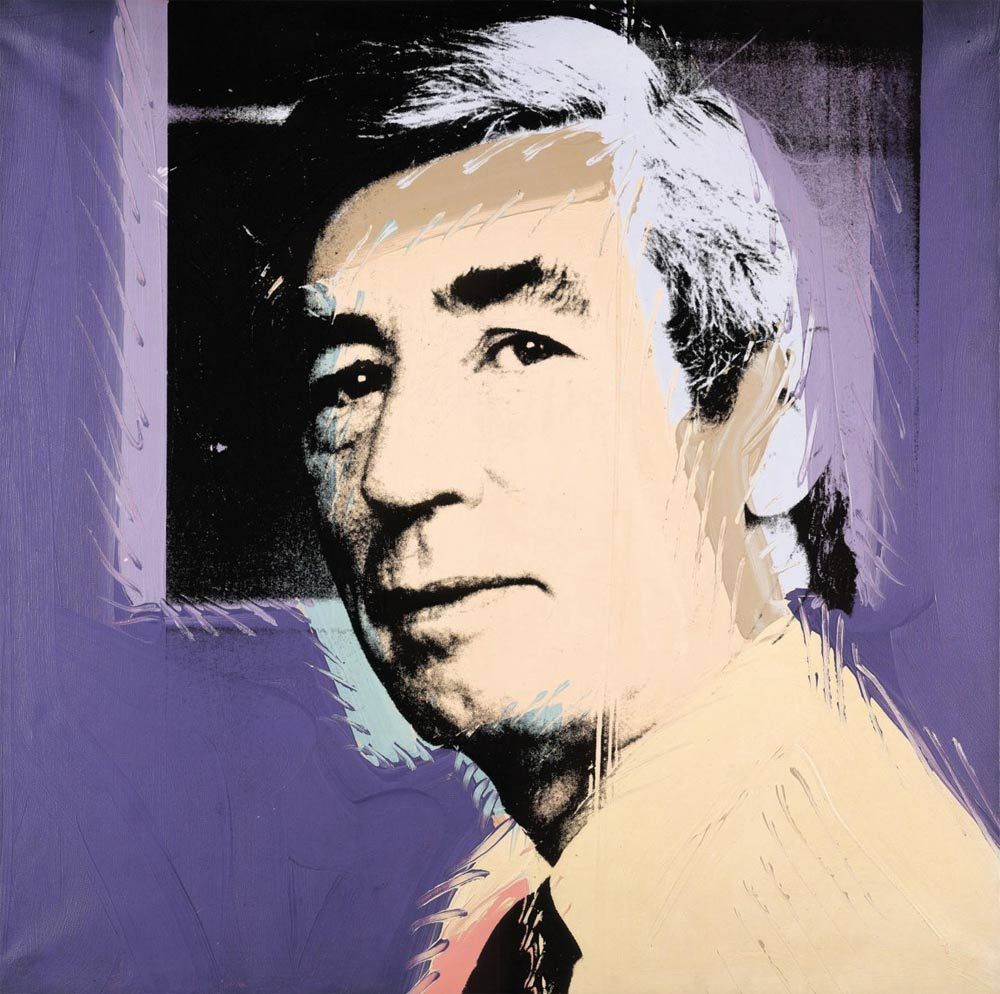

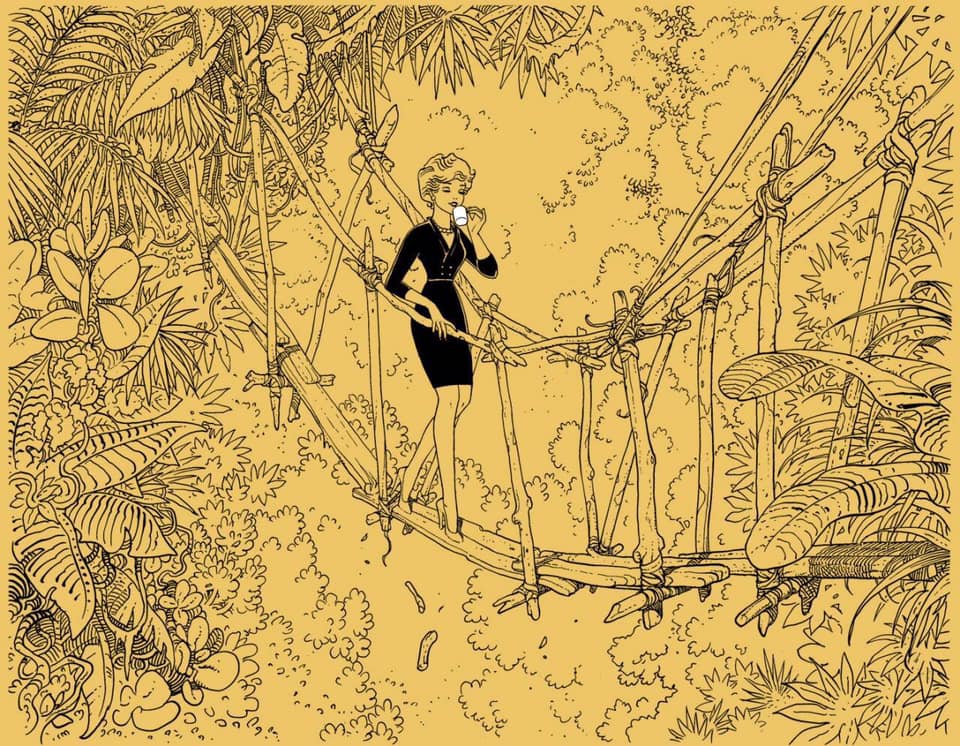

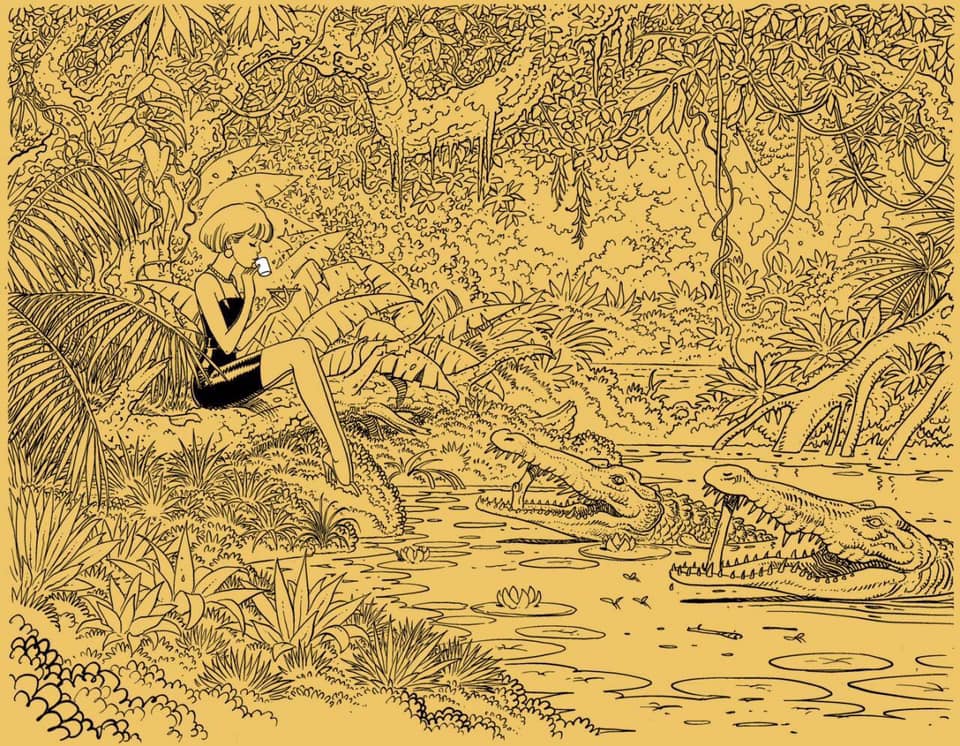

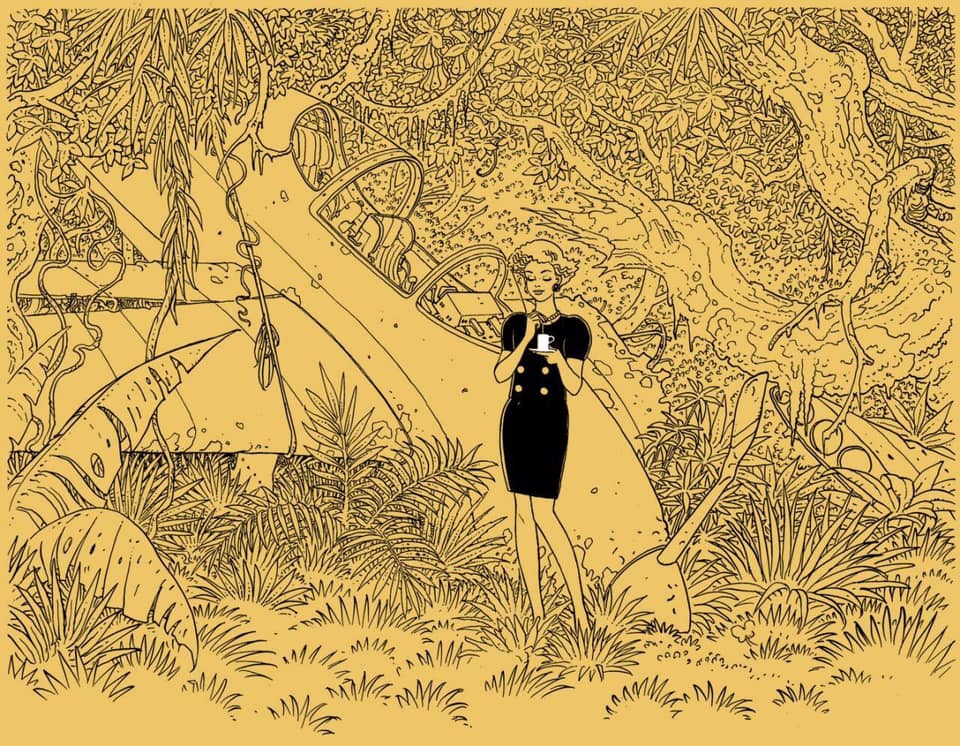

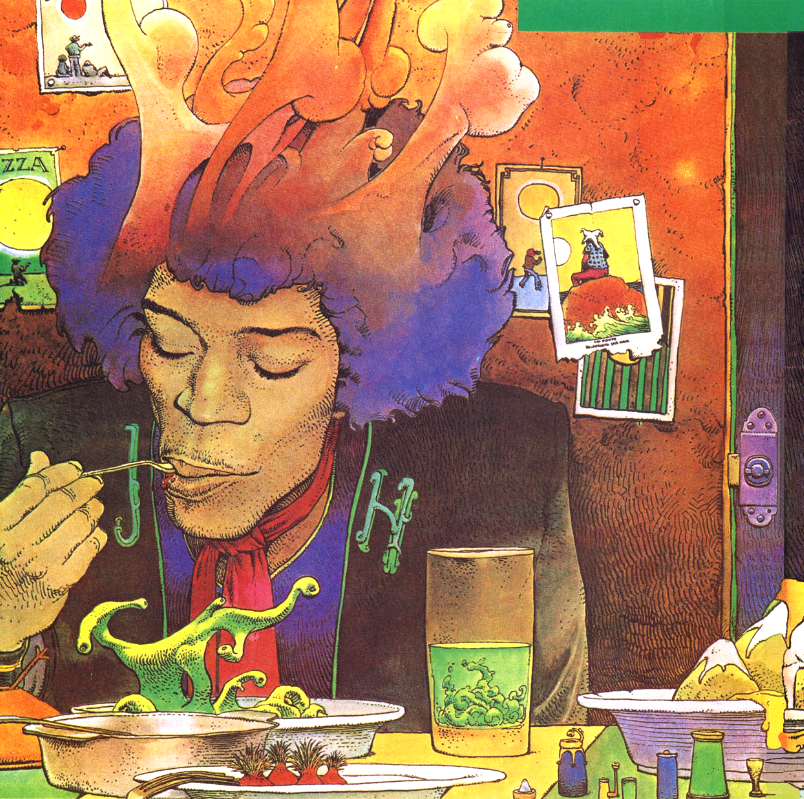

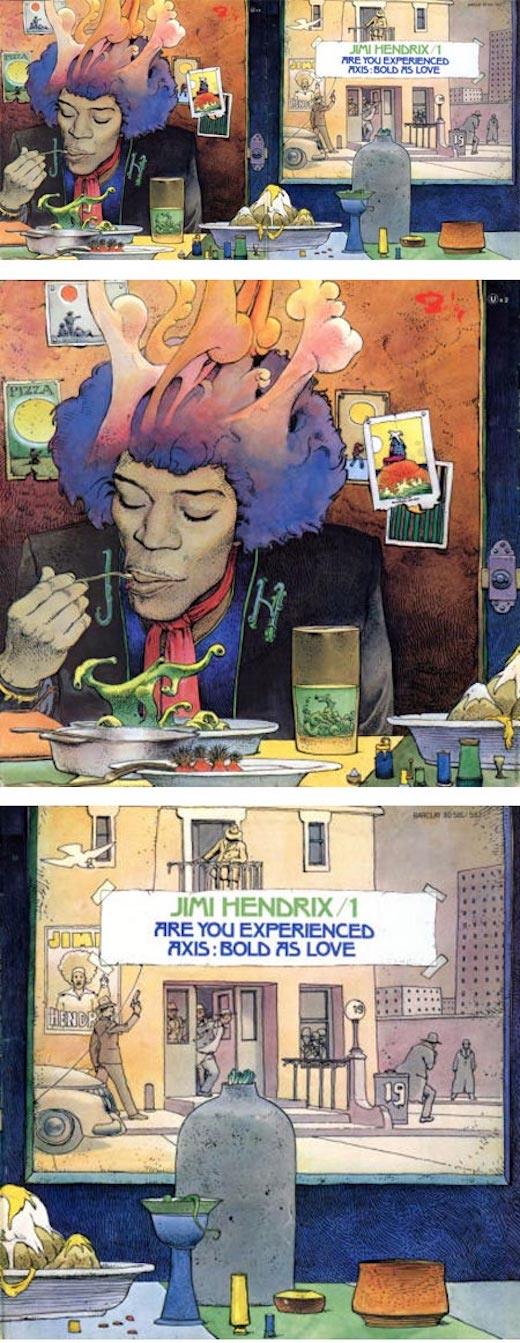

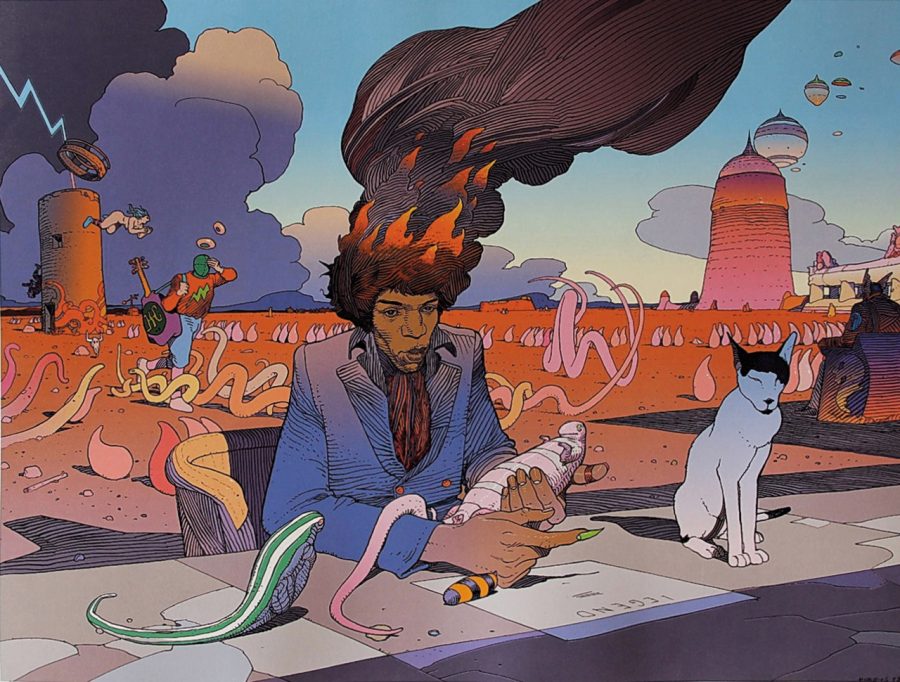

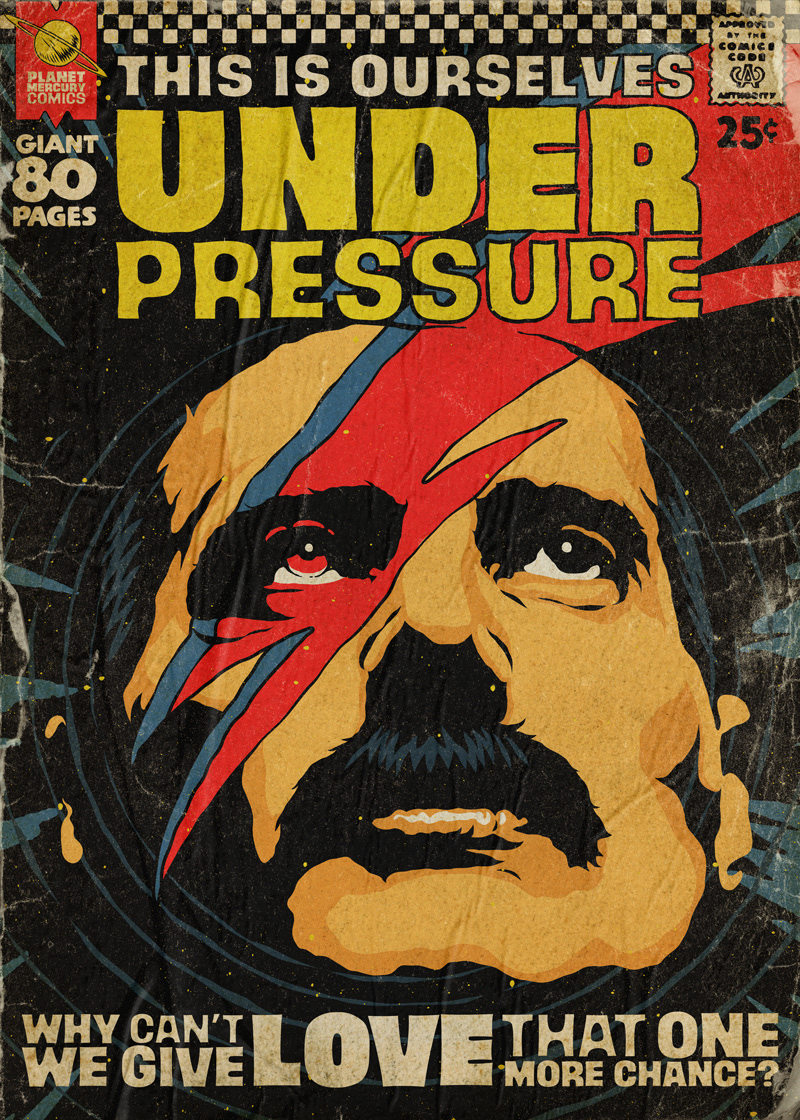

David Bowie’s larger-than-life personas surely deserve to live on, transmitted not only via his music but by way of his posthumous transformation into a series of pulp and comic heroes as imagined by screenwriter and designer Todd Alcott, who has given the same treatment to beloved musical characters like Prince and Bob Dylan.

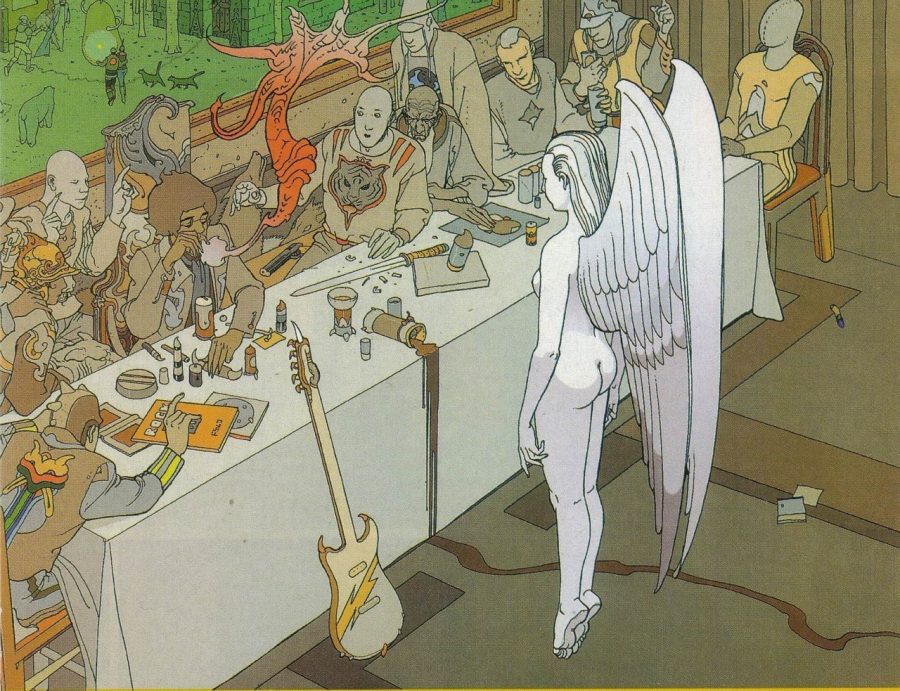

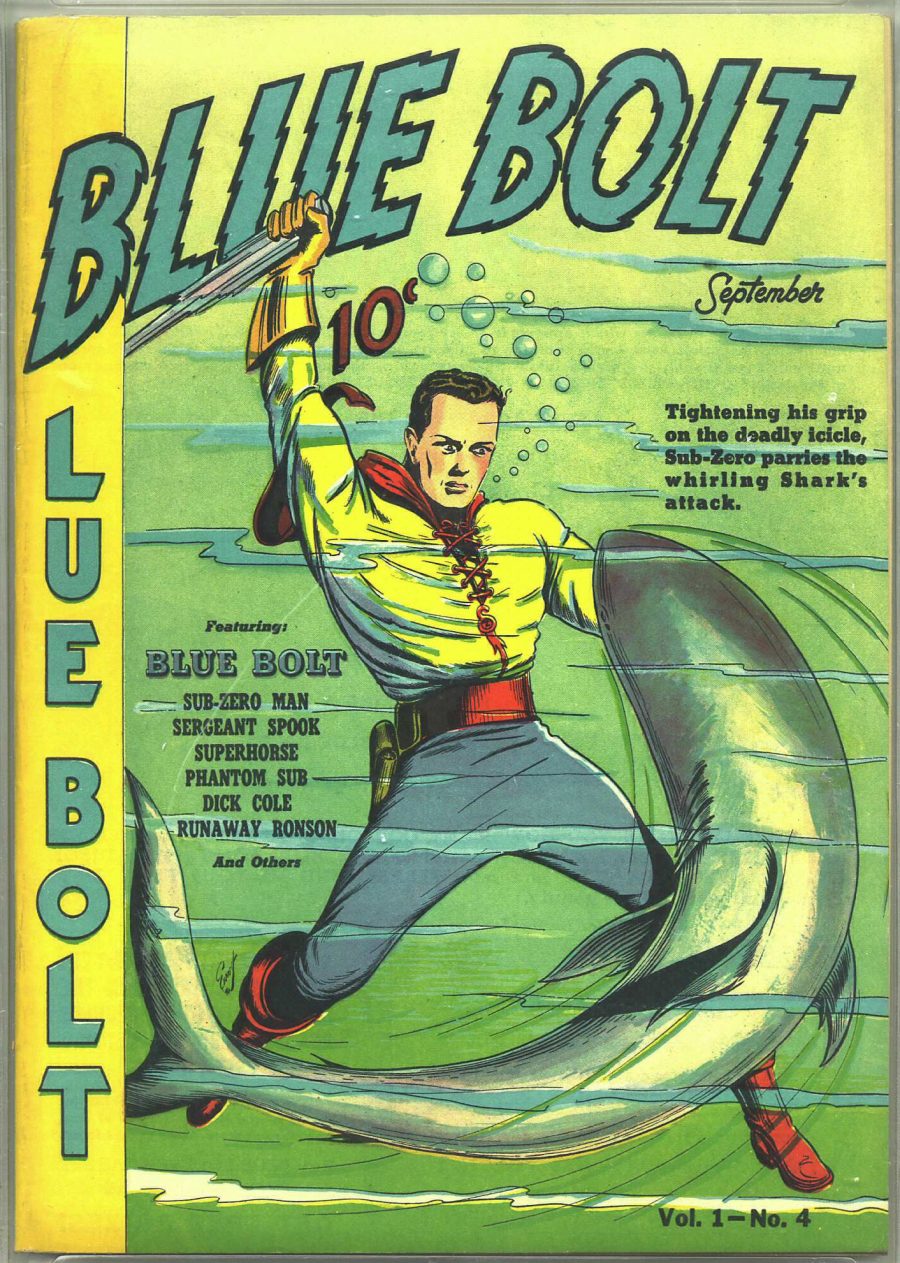

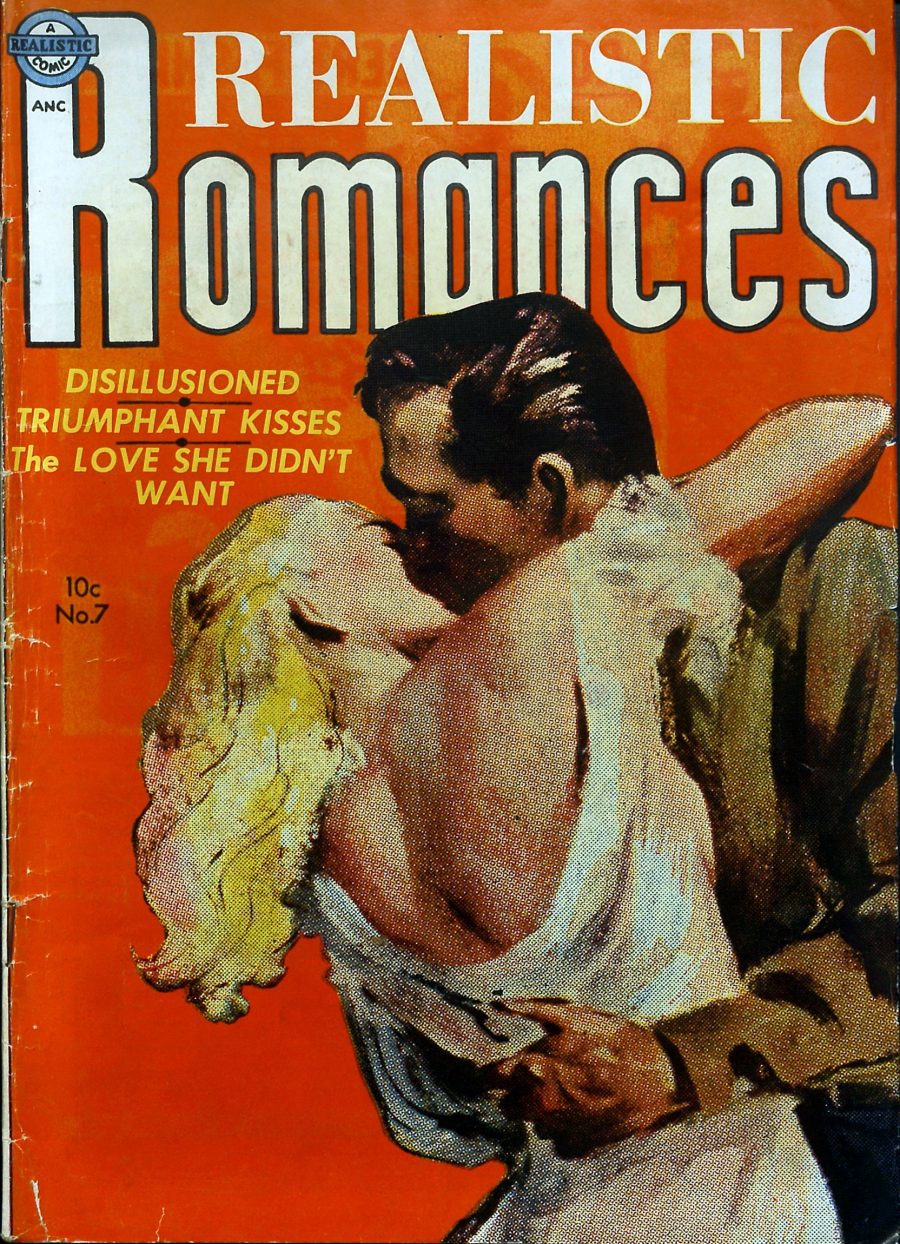

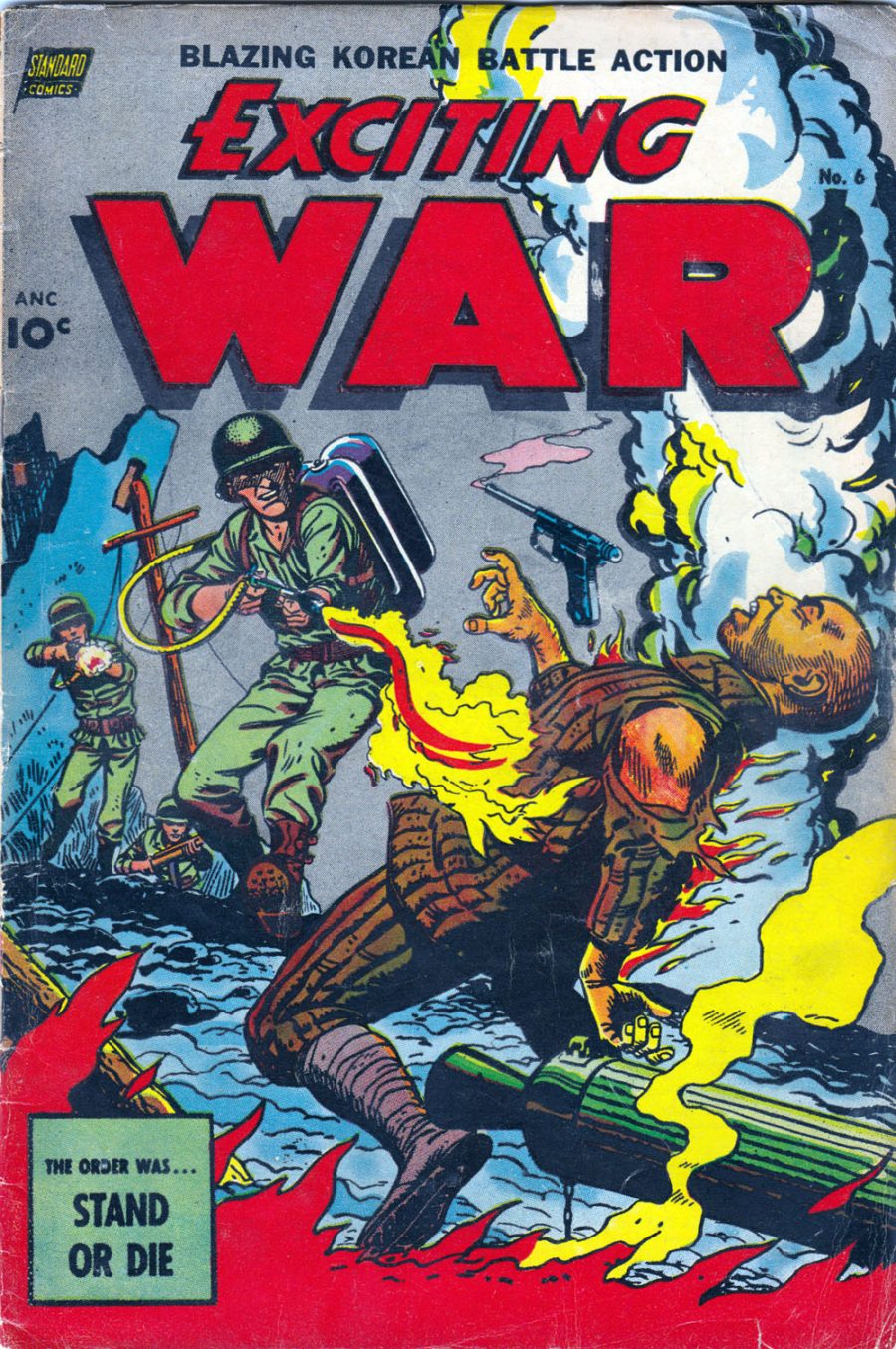

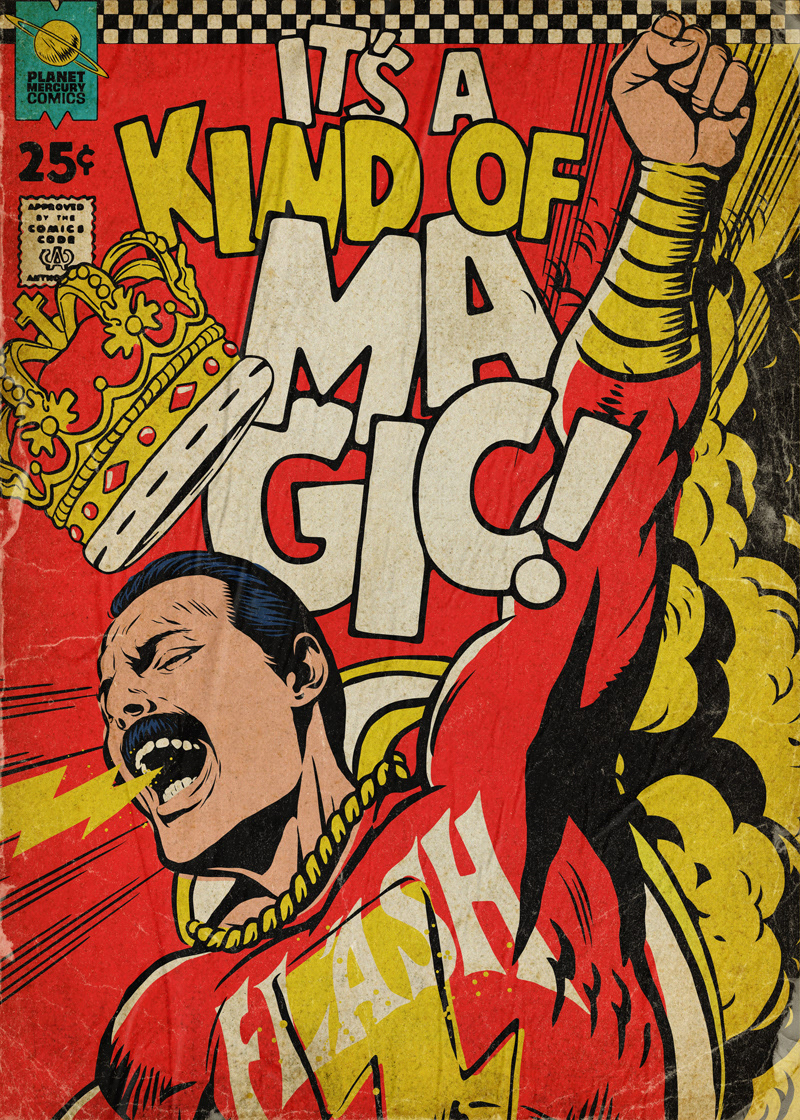

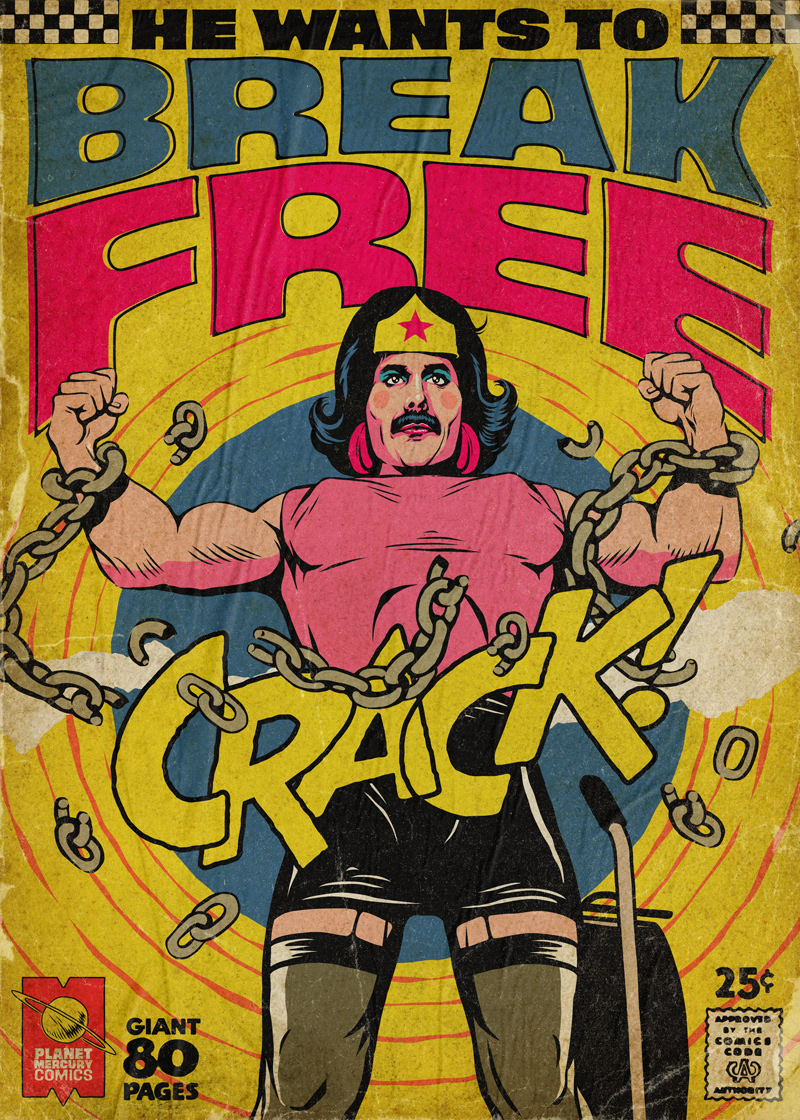

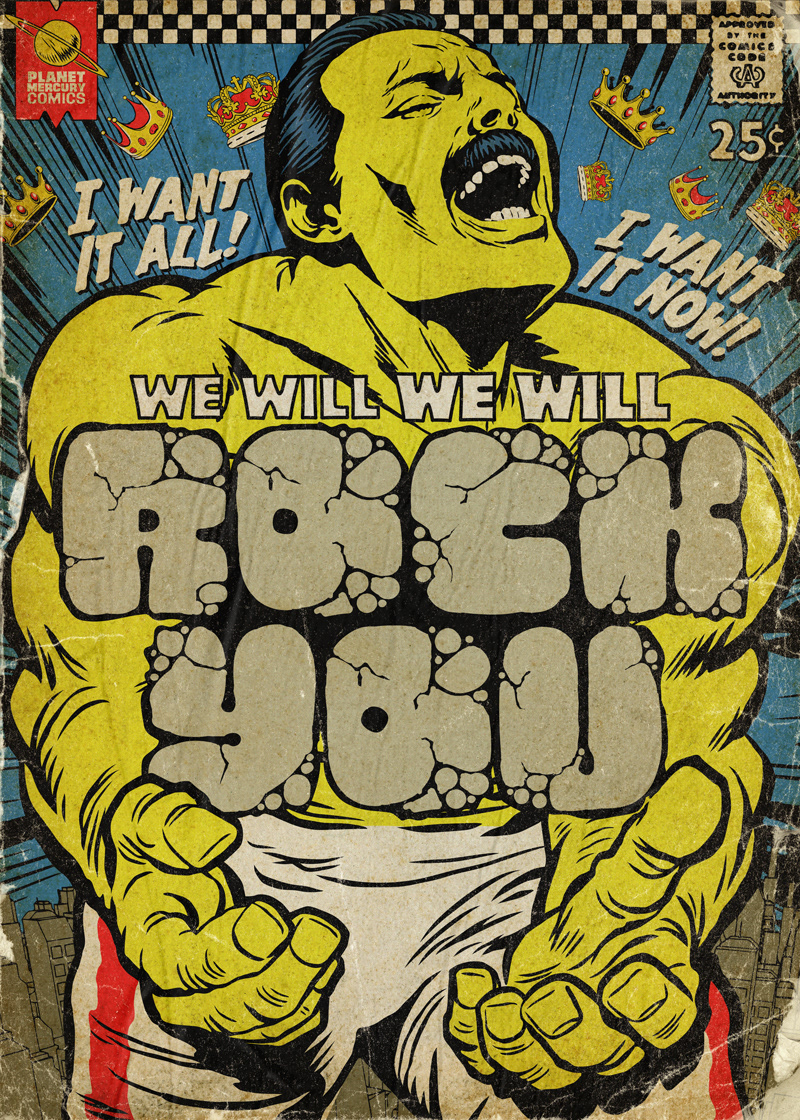

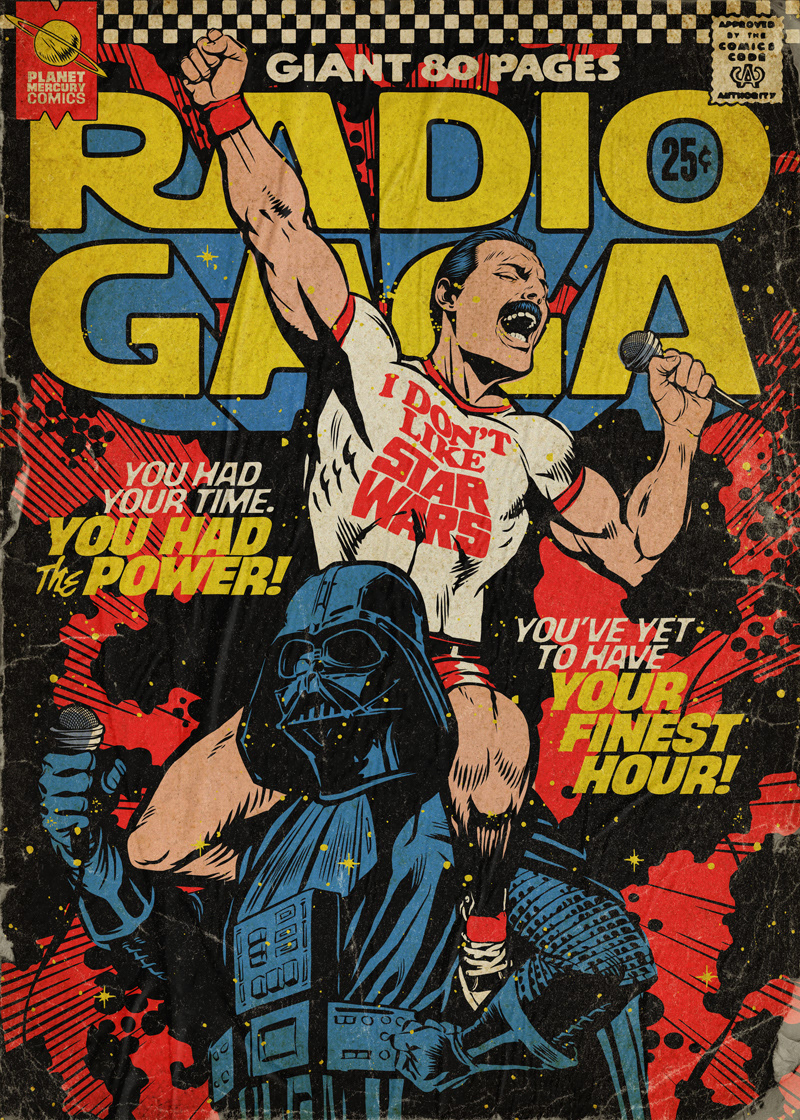

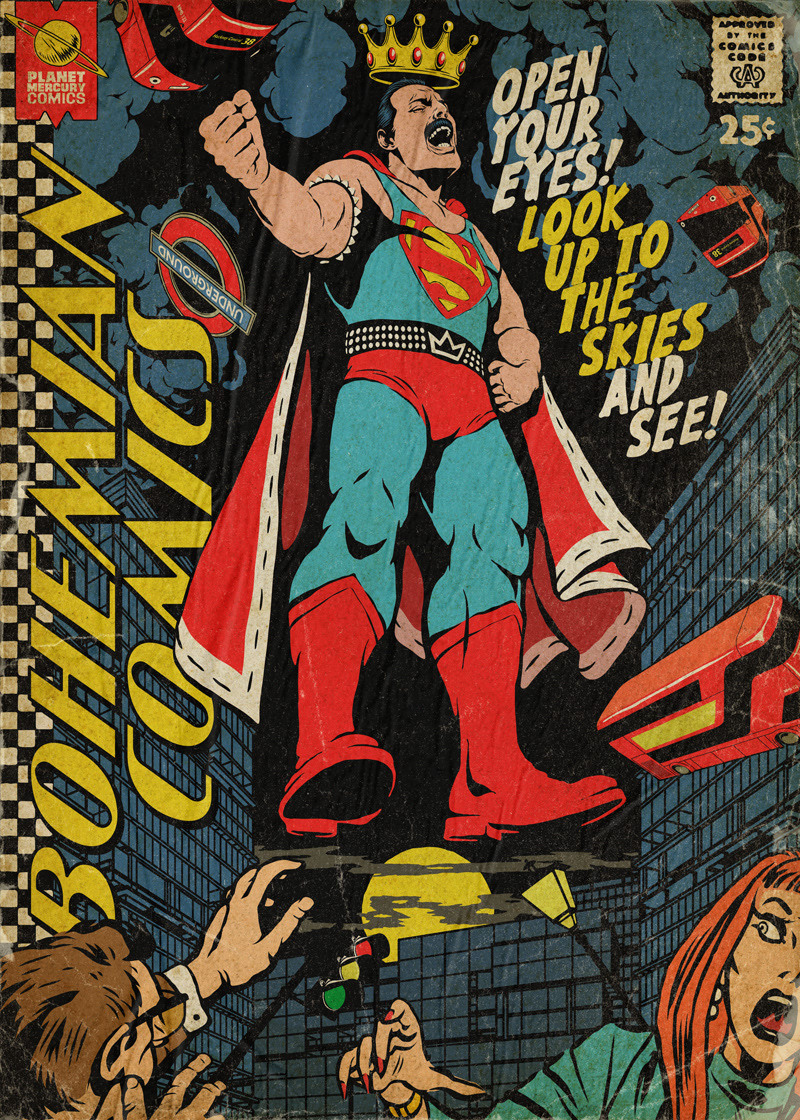

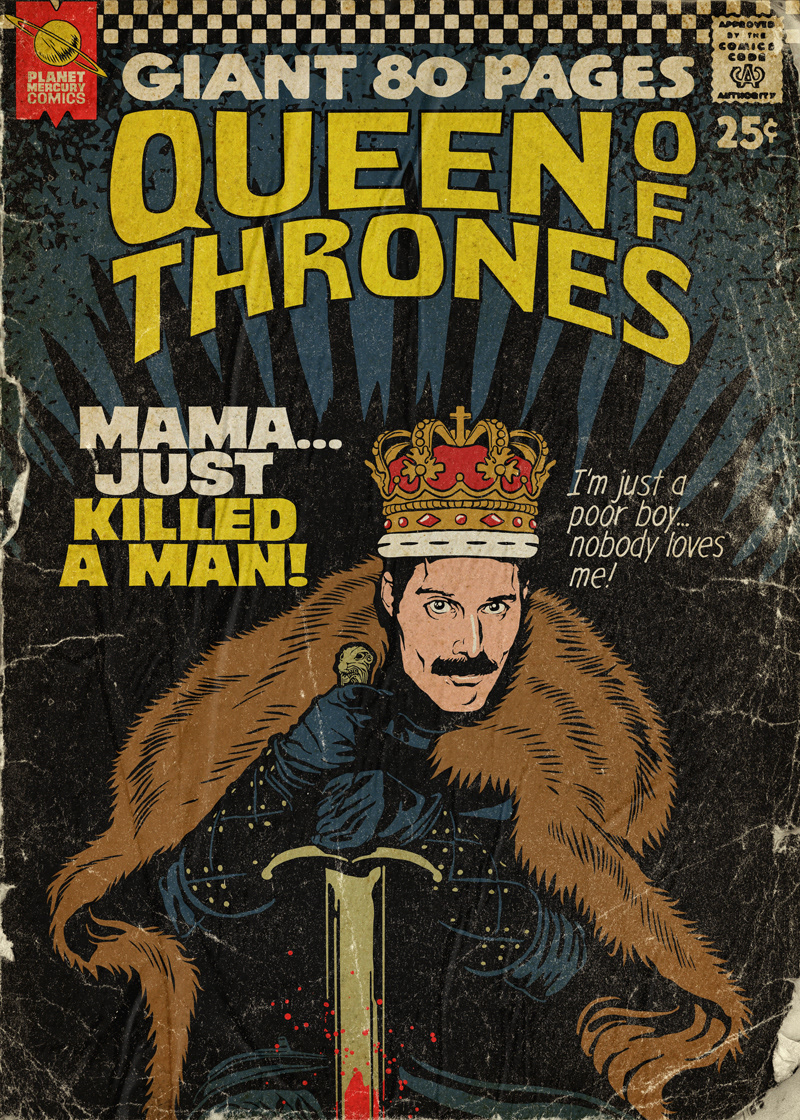

Performing a similar service for Freddie Mercury, Brazilian artist Butcher Billy satisfies the cultural craving for demigods in his immortalization of Freddie Mercury as various heroes like The Hulk, Superman, and Shazam (or “Flash”); a contender for the Iron Throne; and himself: riding on Darth Vader’s shoulders, breaking free in housewife drag, and sporting Bowie’s Aladdin Sane lightning bolt. What are the superpowers of these super-Freddies? The usual smashing, punching, and flying, it seems, but also the essentials of his real-life power—an impossibly big personality, huge stage presence, personal magnetism, and a godlike force of a voice.

Add to these characteristics a unique talent for writing lyrics punchier than your favorite Twitter feed, and we have the makings of a modern epic giant with abilities that seemed to surpass those of mere mortals, with the swagger and ego to match. This tribute to Mercury is unabashed hero worship, turning the singer into an archetype. In the simple, bold, colorful lines of comic cover art we might just see that there’s a Freddie Mercury in all of us, wanting to break free, pump a fist in the air, and belt out our biggest feelings in capital letters and giant exclamation marks.

See more “Planet Mercury Comics” below and at Butcher Billy’s Behance site.

via Laughing Squid

Related Content:

David Bowie Songs Reimagined as Pulp Fiction Book Covers: Space Oddity, Heroes, Life on Mars & More

Scenes from Bohemian Rhapsody Compared to Real Life: A 21-Minute Compilation

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness