“Speculations about the creators of Tarot cards include the Sufis, the Cathars, the Egyptians, Kabbalists, and more,” writes “expert cartomancer” Joshua Hehe. All of these suppositions are wrong, it seems. “The actual historical evidence points to northern Italy sometime in the early part of the 1400s,” when the so-called “major arcana” came into being. “Contrary to what many have claimed, there is absolutely no proof of the Tarot having originated in any other time or place.”

A bold claim, yet there are precedents much older than tarot: “A few decades before the Tarot was born, ordinary playing cards came to Europe by way of Arabs, arriving in many different cities between 1375 and 1378. These cards were an adaptation of the Islamic Mamluk cards,” with suits of cups, swords, coins, and polo sticks, “the latter of which were seen by Europeans as staves.”

Whether the playing cards invented by the Mamluks were used for divination may be a matter of controversy. The history and art of the Mamluk sultanate itself is a subject worthy of study for the tarot historian. Originally a slave army (“mamluk” means “slave” in Arabic) under the Ayyubid sultans in Egypt and Syria, the Mamluks overthrew their rulers and created “the greatest Islamic empire of the later Middle Ages.”

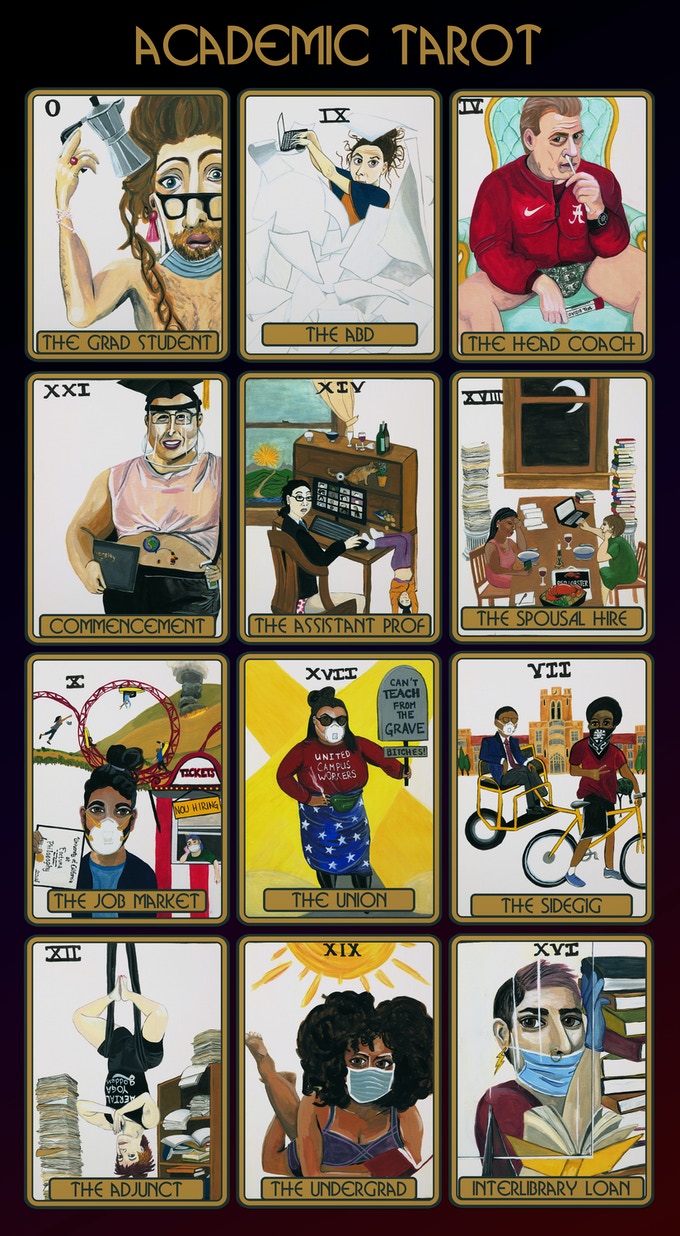

What does this have to do with tarot reading? These are academic concerns, perhaps, of little interest to the average tarot enthusiast. But then, the average tarot enthusiast is not the audience for the “Academic Tarot,” a project of the Visionary Futures Collective, or VFC, a group of 22 scholars “fighting for what higher education needs most,” Stephanie Malak writes at Hyperallergic, “a bringing together of thinkers who ‘believe in the transformational power and vital importance of the humanities.’”

To that end, the Academic Tarot features exactly the kinds of characters who love to chase down abstruse historical questions—characters like the lowly, confused Grad Student, standing in here for The Fool. It also features those who can make academic life, with its endless rounds of meetings and committees, so difficult: figures like The President (see here), doing duty here as the Magician, and pictured shredding “campus-wide COVID results.”

The VFC, founded in the time of COVID-19 pandemic and “in the midst of the long-overdue national reckoning led by the Black Lives Matter movement,” aims to “trace the contours of things that define our shared human condition,” says Collective member Dr. Brian DeGrazia. In the case of the Academic Tarot, the conditions represented are shared by a specific subset of humans, many of whom responded to “feelings surveys” put out by the VFC in a biweekly newsletter.

The surveys have been used to make art that reflects the experiences of the grad students, professors, and professional staff working the academic humanities at this time:

VFC artist-in-residence Claire Chenette, a Grammy-nominated Knoxville Symphony Orchestra musician furloughed due to COVID-19, brought the tarot cards to life. What began as a three-card project to complement the VFC newsletter grew in spirit and in number.

“In tarot, the cards read us,” the VFC writes, “telling a story about ourselves that can provide clarity, guidance and hope.” What story do the 22 Major Arcana cards in the Academic Tarot tell? That depends on who’s asking, as always, but one gets the sense that unless the querent is familiar with life in a higher-ed humanities department, these cards may not reveal much. For those who have seen themselves in the cards, however, “the images made them laugh out loud,” says Chenette, or “they hit hard. Or… they even made them cry, but… it needed to happen.”

Struggling through yet another pandemic semester of attempting to teach, research, write, and generally stay afloat? The Academic Tarot cards are currently sold out, but you can pre-order now for the second run.

via Hyperallergic

Related Content:

Behold the Sola-Busca Tarot Deck, the Earliest Complete Set of Tarot Cards (1490)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness