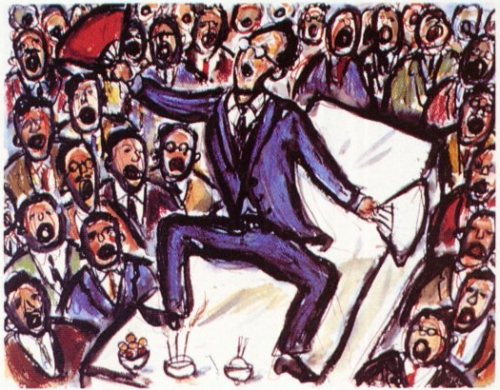

“One of the many remarkable things about Charlie Chaplin,” wrote Roger Ebert, “is that his films continue to hold up, to attract and delight audiences.” Richard Brody described Chaplin as not just “alone among his peers of silent-comedy genius,” but also as a maker of “great talking pictures.” Jonathan Rosenbaum asked, “Has there ever been another artist — not just in the history of cinema, but maybe in the history of art — who has had more to say, and in such vivid detail, about what it means to be poor?” Andrew Sarris called Chaplin “arguably the single most important artist produced by the cinema, certainly its most extraordinary performer and probably still its most universal icon.” “For me,” wrote Leonard Maltin, “comedy begins with Charlie Chaplin.”

And so we see that Chaplin, nearly forty decades after his death, maintains his high critical reputation — while also having enjoyed the absolute height of movie-stardom back in the silent era.

Vanishingly few artists of any kind manage to combine such blockbusting commercial success with such flying-colors critical success. That alone might give you good enough reason to plunge into Chaplin’s filmography, but know that you can begin that cinematic adventure for free right here on Open Culture in our archive of more than 60 Charlie Chaplin films on the web.

There you’ll find short comedies like 1914’s Kids Auto Race at Venice, which introduced his famous penniless protagonist “The Tramp”; the following year’s The Tramp, which made it into a phenomenon; 1919’s Sunnyside, in which we find out what happens when Chaplin’s gracefully hapless comedic persona winds up on the farm; and 1925’s The Gold Rush, the film Chaplin most wanted to be remembered for.

But though Chaplin’s oeuvre couldn’t be easier to start watching and laughing at, coming to appreciate the full scope of his craft — in the way that the critics quoted above have spent careers doing — may take time. After all, the man made 80 movies over his 75-year entertainment career, a kind of productivity that, even leaving the considerable artistry aside, cinema may never see again. You can dive into our collection of Chaplin films here.

Related Content:

101 Free Silent Films: The Great Classics

Colorized Photos Bring Walt Whitman, Charlie Chaplin, Helen Keller & Mark Twain Back to Life

Charlie Chaplin Does Cocaine and Saves the Day in Modern Times (1936)

4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More

Colin Marshall writes elsewhere on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, and the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future? Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.