No old stuff for me, no bestial copyings of arches and columns and cornices. Me, I’m new.

— architect William Van Alen, designer of the Chrysler Building

Many people claim the Chrysler Building as their favorite New York City edifice and actor John Malkovich is one such:

It’s so crazy and vigorous in its execution, so breathtaking in its vision, so brilliantly eccentric.

Malkovich, who’s not shy about taking potshots at the city’s “violence and filth” in the BBC documentary short above, rhapsodizes over Detroit industrialist Walter P. Chrysler’s “latter day pyramid in Manhattan.”

Malkovich’s unmistakable voice, pegged by The Guardian as “wafting, whispery, and reedy” and which he himself poo poos as sounding like it belongs to someone who’s “labored under heavy narcotics for years,” pairs well with descriptions so plummy, one has to imagine he penned them himself. (No writer is credited.)

After showing us the open-to-the-public lobby’s “delicious Art Deco fittings,” ceiling mural, and intricate, veneered elevator doors, Malkovich gives us a tour of some off-limits upper floors.

Unlike the Empire State Building, which bested the Chrysler Building’s brief record as the world’s tallest building (1046 feet, 77 stories), you can’t purchase tickets to admire the view from the top.

But Malkovich has the star power to gain access to Celestial, the seventy-first floor observatory that has been closed to the public since 1945 and is currently occupied by a private firm.

He also has a wander around the barren Cloud Club, a supper club and speakeasy for gentleman one percenters. Its mishmash of styles represented a concession on architect Van Alen’s part. The building’s exterior was an elegant modernist homage to Chrysler’s hubcaps and hood ornaments, but between the 66th and 68th floor, the Cloud Club catered to the promiscuous tastes of the rich and powerful — Tudor, Olde English, Neo-Classical…

The New York Times reports that it boasted what “was reputed to be the grandest men’s room in all of New York.”

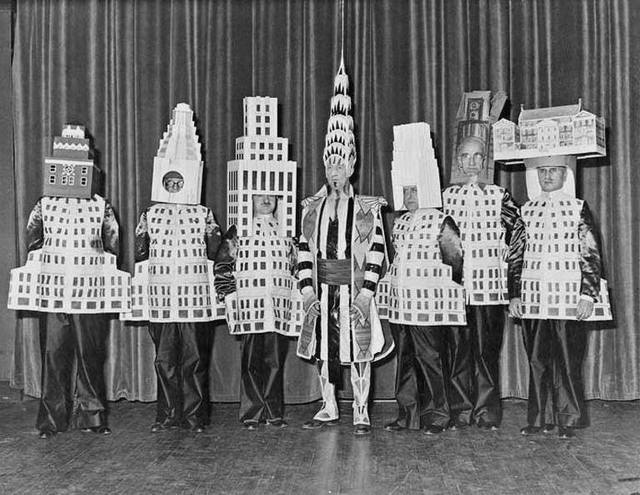

A Duke Ellington soundtrack and vintage footage featuring Van Alen costumed to resemble his famous creation supply a taste of the excitement that heralded the building’s 1930 opening, even if those with a fear of heights may swoon at the sight of pretty young things reclining on high beams and performing other feats of derring-do.

Malkovich, ever the cool customer, displays his lack of vertigo by casually propping a foot on the rooftop’s edge to commune with the iconic eagle-headed gargoyles.

The building’s unique flourishes caused a sensation, but not everyone was a fan.

Malkovich clearly savors his swipe at critics who decried the new building as too shiny:

Fortunately these critics are long dead so we can’t even call their offices and taunt them as they should be taunted.

He’s more temperate when it comes to author and social philosopher Lewis Mumford, whose beef with the skyscraper is understandable, given the historic context — the stock market crashed the day after the secretly constructed spire was riveted into place:

Such buildings show one of the real dangers of a plutocracy: it gives the masters of our civilization an unusual opportunity to exhibit their barbarous egos, with no sense of restraint or shame.

Nearly one hundred years later, barbarous egos continue to erect skyscraping temples to their own vanity, but as Malkovich points out, they’re far blander, if taller.

The Chrysler Building is now widely recognized as one of New York City’s most magnificent jewels, and the Landmarks Preservation Commission recently approved plans to construct a public observation deck on the Chrysler Building’s 61st floor, just above its iconic Art Deco eagles, though it’s too early to tell if it will be ready in time for a centennial celebration.

Until then, the general public must content itself with exploring the Chrysler Building’s lobby during weekday business hours.

Related Content:

Why Do People Hate Modern Architecture?: A Video Essay

Famous Architects Dress as Their Famous New York City Buildings (1931)

Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.