We’ve all have heard of the fuchsia, a flower (or genus of flowering plant) native to Central and South America but now grown far and wide. Though even the least botanically literate among us know it, we may have occasional trouble spelling its name. The key is to remember who the fuchsia was named for: Leonhart Fuchs, a German physician and botanist of the sixteenth century. More than 450 years after his death, Fuchs is remembered as not just the namesake of a flower, but as the author of an enormous book detailing the varieties of plants and their medicinal uses. His was a landmark achievement in the form known as the herbal, examples of which we’ve featured here on Open Culture from ninth- and eighteenth-century England.

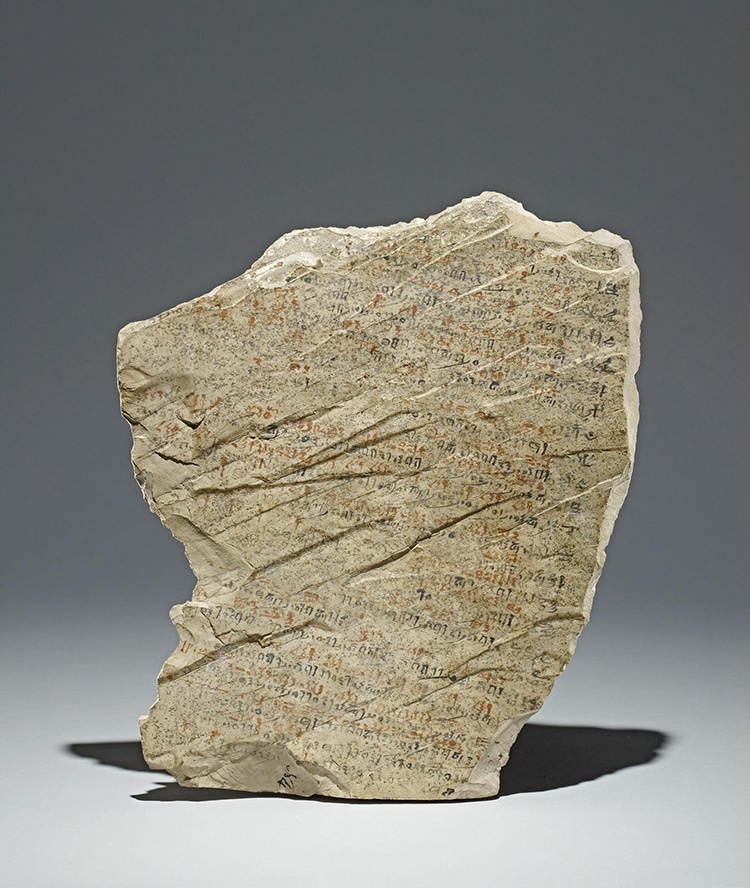

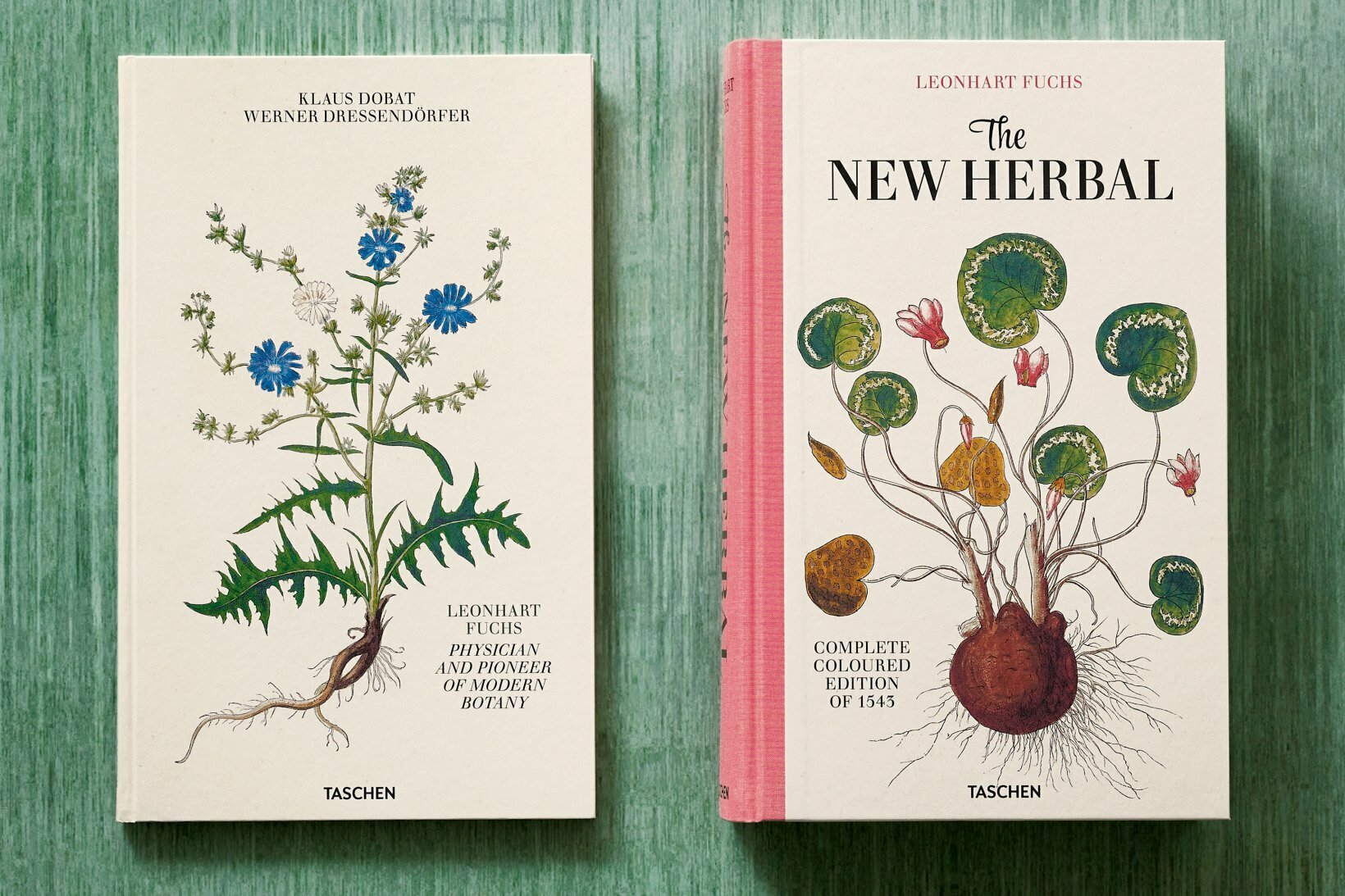

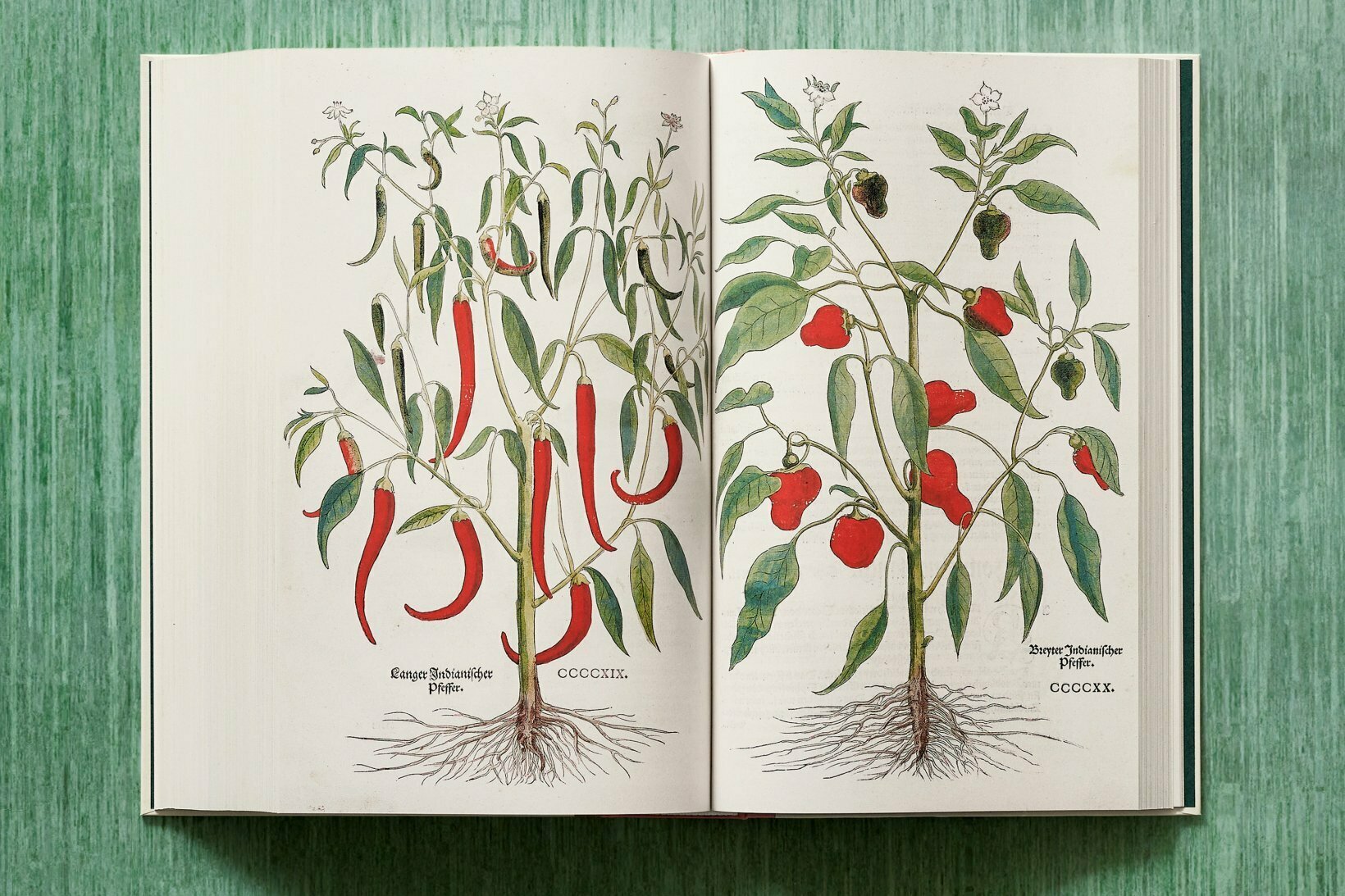

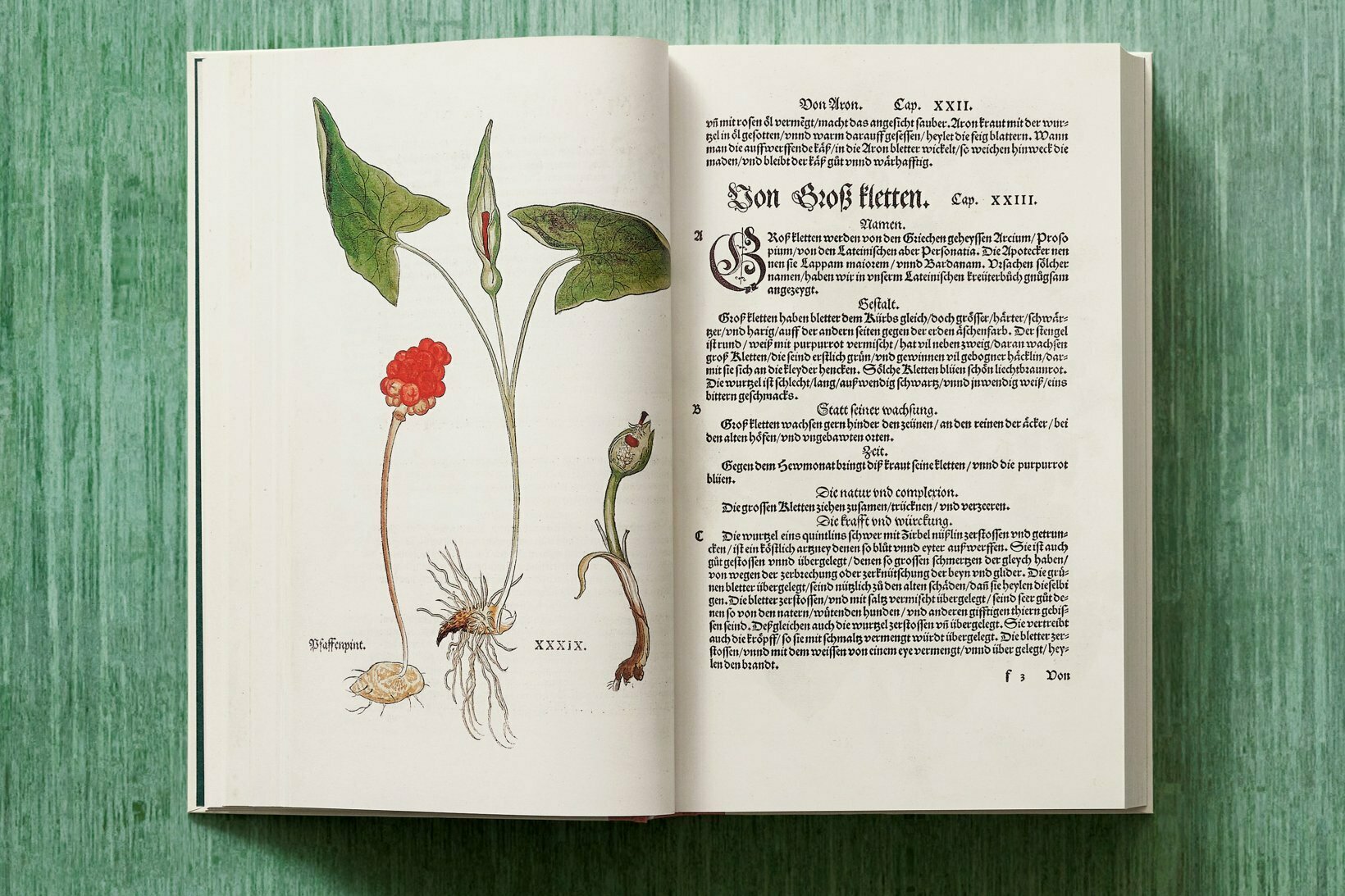

But De Historia Stirpium Commentarii Insignes, as this work was known upon its initial 1542 publication in Latin, has worn uncommonly well through the ages. Or rather, Fuchs’ personal, hand-colored original has, coming down to us in 2022 as the source for Taschen’s The New Herbal. “A masterpiece of Renaissance botany and publishing,” according to the publisher, the book includes “over 500 illustrations, including the first visual record of New World plant types such as maize, cactus, and tobacco.”

Buyers also have their choice of English, German, and French editions, each with its own translations of Fuchs’ “essays describing the plants’ features, origins, and medicinal powers.” (You can also read a Dutch version of the original online at Utrecht University Library Special Collections.)

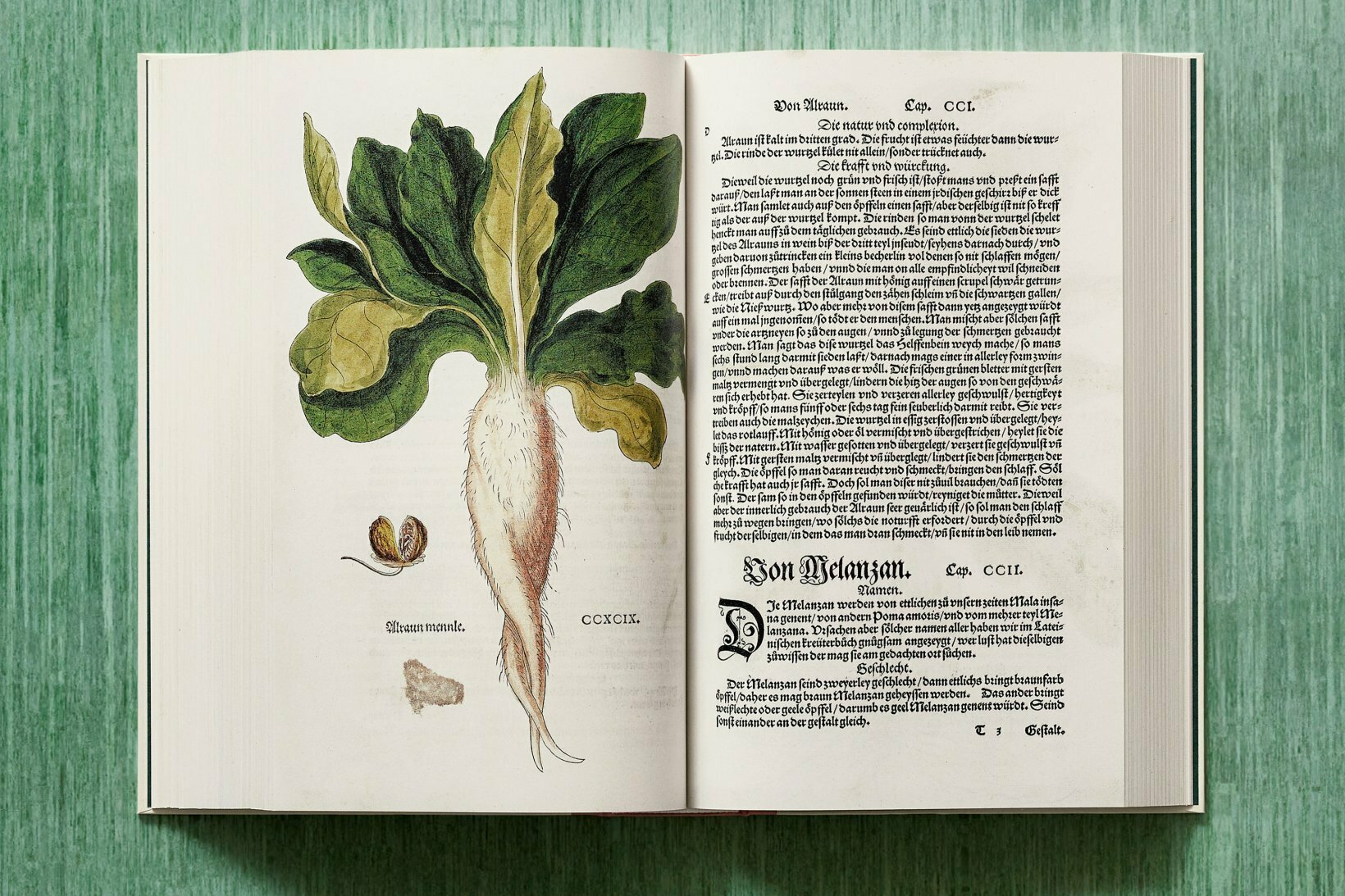

Naturally, some of the information contained in these nearly five-century-old scientific writings will be a bit dated at this point, but the appeal of the illustrations has never dimmed. “Fuchs presented each plant with meticulous woodcut illustrations, refining the ability for swift species identification and setting new standards for accuracy and quality in botanical publications.” Over 500 of them go into the book: “Weighing more than 10 pounds,” writes Colossal’s Grace Ebert, “the nearly 900-page volume is an ode to Fuchs’ research and the field of Renaissance botany, detailing plants like the leafy garden balsam and root-covered mandrake.”

Taschen’s reproductions of these works of botanical art look to do justice to Leonhart Fuchs’ legacy, especially in the brilliance of their colors. It’s enough to reinforce the assumption that the man has received tribute not just through fuchsia the flower but fuchsia the color as well. But such a dual connection turns out to be in doubt: the color’s name derives from rosaniline hydrochloride, also known as fuchsine, originally a trade name applied by its manufacturer Renard frères et Franc. The name fuschine, in turn, derives from fuchs, the German translation of renard. The New Herbal is, of course, a work of botany rather than linguistics, but it should nevertheless stimulate in its beholders an awareness of the interconnection of knowledge that fired up the Renaissance mind.

via Colossal

Related content:

Two Million Wondrous Nature Illustrations Put Online by The Biodiversity Heritage Library

A Beautiful 1897 Illustrated Book Shows How Flowers Become Art Nouveau Designs

1,000-Year-Old Illustrated Guide to the Medicinal Use of Plants Now Digitized & Put Online

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.