Once, the United States was known for sending forth the world’s most complained-about international tourists; today, that dubious distinction arguably belongs to China. But it wasn’t so long ago that the Chinese tourist was a practically unheard-of phenomenon, especially in the West. That’s an important contextual element to understand when considering the work of photographer Tseng Kwong Chi, who traveled around America taking pictures of himself at various recognizable monuments and landmarks while wearing a suit most commonly associated with Chairman Mao. The figure that emerged from this project is the subject of the new Nerdwriter video above.

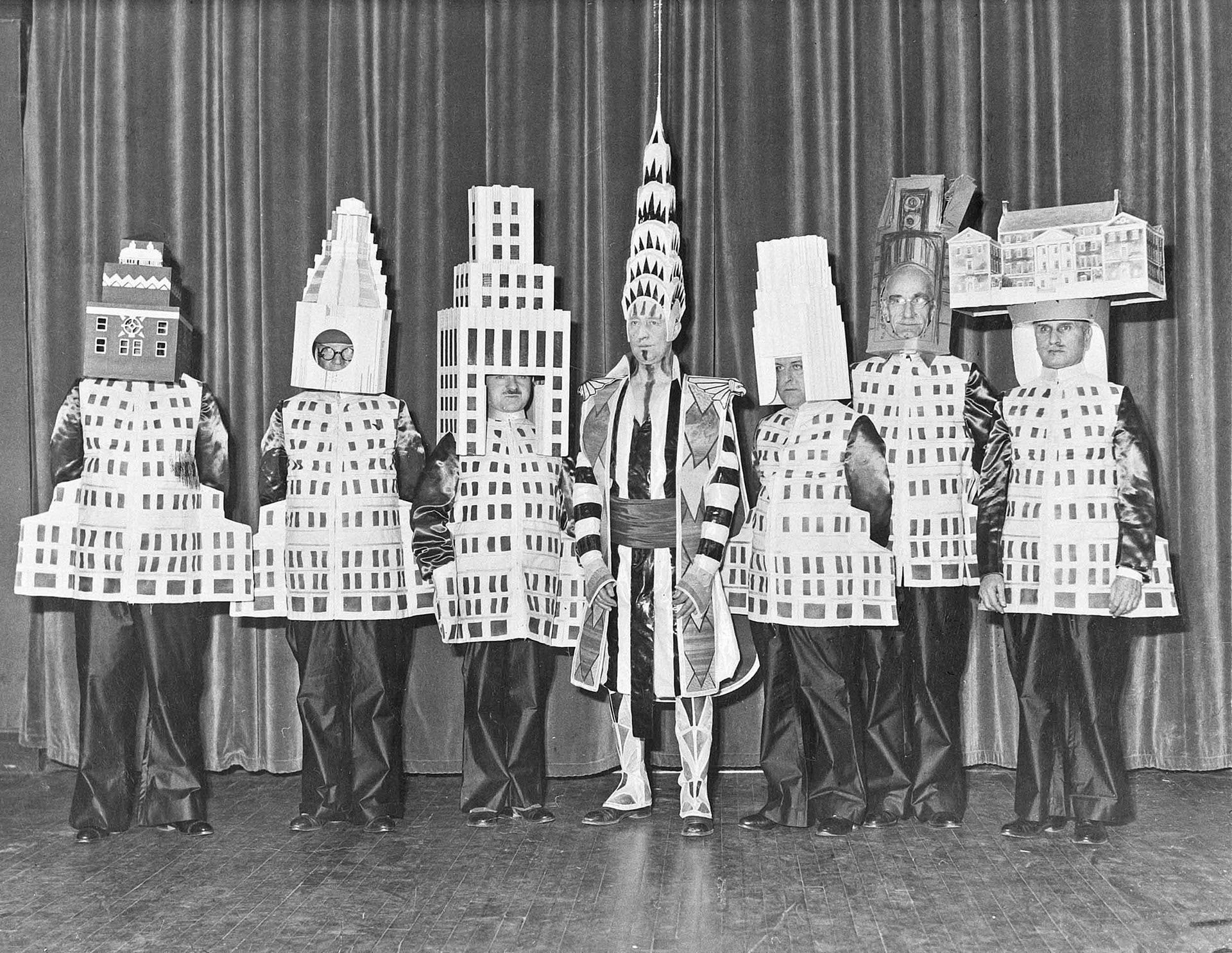

“He called this character ‘an ambiguous ambassador,’ and, in a series he called ‘East Meets West,’ posed him — posed himself — in front of various icons of touristic America,” writes Brian Dillon in a New Yorker piece on Tseng’s work. “He leaps into the air in front of the Brooklyn Bridge, stands impassive beside Mickey Mouse at Disneyland, gazes off into the distance with Niagara Falls behind him.”

Inspired by Richard Nixon’s 1972 visit to China and Deng Xiaoping’s 1979 visit to the U.S., Tseng produced most of these photos in the late seventies and early eighties, and even “took the ambiguous ambassador to Europe, where he appears heroic before the Arc de Triomphe, and diminutive between two policemen at the Tower of London.”

Born in British Hong Kong, then partially raised in Canada and educated in Paris, Tseng arrived in New York in 1979, ready to join the downtown scene that included Jean-Michel Basquiat, Ann Magnuson, Cindy Sherman, and Keith Haring. It’s for his documentation of Haring’s work, in fact, that he remains most widely known, 35 years after his own AIDS-related death. But now, as taking pictures of oneself in famous places around the world becomes an increasingly universal practice, “East Meets West” draws more and more attention. Maybe, in an art world where cultural identity is so fiercely declared and defended, the very ambiguity of the ambassador portrayed by Tseng — who, as Evan “Nerdwriter” Puschak emphasizes, “didn’t want to be known as a Chinese artist, or an Asian-American artist, or a gay artist; he just wanted to be an artist” — has become that much more compelling.

Related Content:

The Iconic Photography of Gordon Parks: An Introduction to the Renaissance American Artist

The Revolutionary Paintings of Jean-Michel Basquiat: A Video Essay

How Dorothea Lange Shot Migrant Mother Perhaps the Most Iconic Photo in American History

Demystifying the Activist Graffiti Art of Keith Haring: A Video Essay

The Photo That Triggered China’s Disastrous Cultural Revolution (1966)

Photographer Bill Cunningham (RIP) on Living La Vie Boheme Above Carnegie Hall

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.