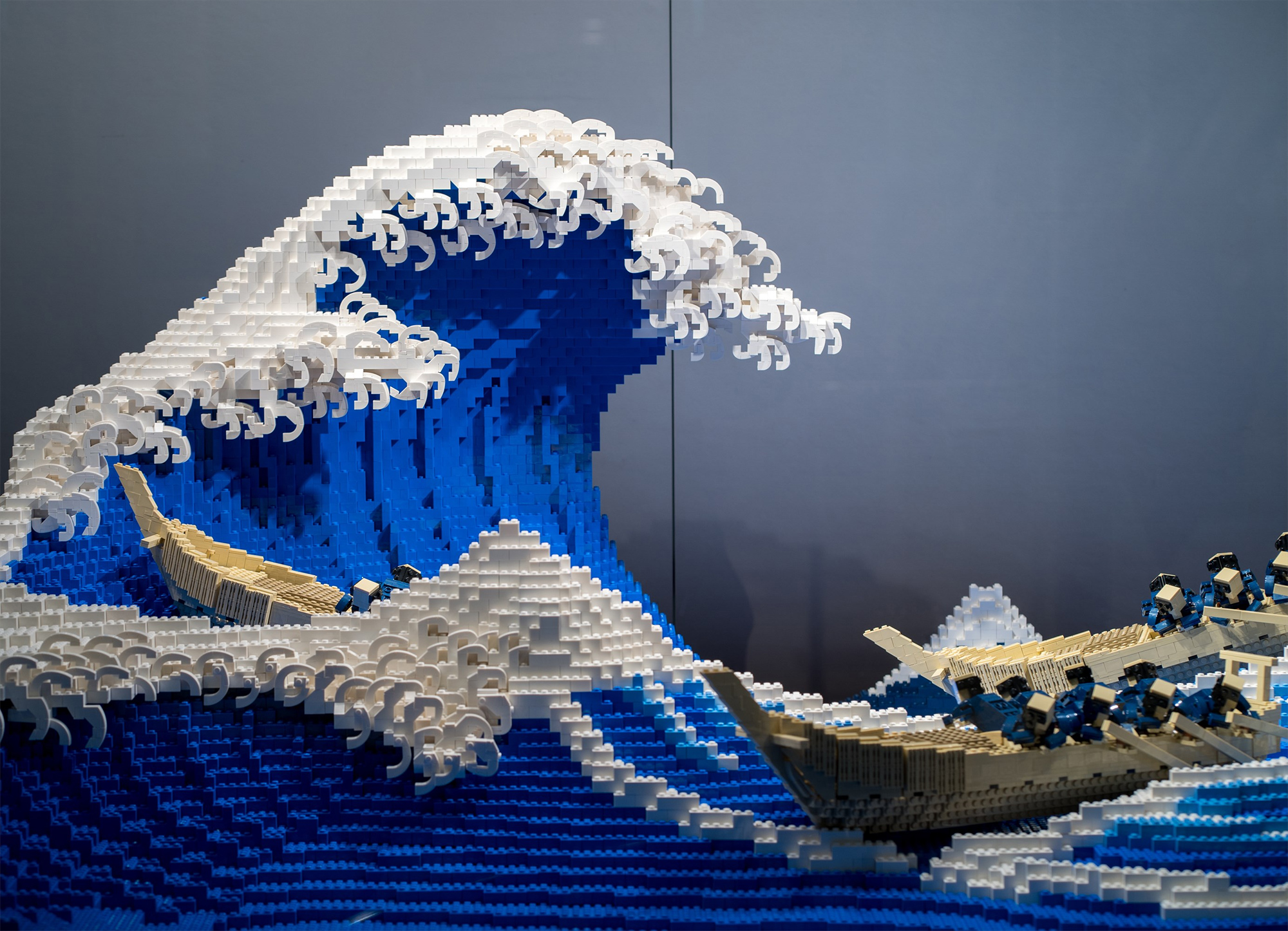

Watch Hokusai’s The Great Wave off Kanagawa Get Entirely Recreated with 50,000 LEGO Bricks

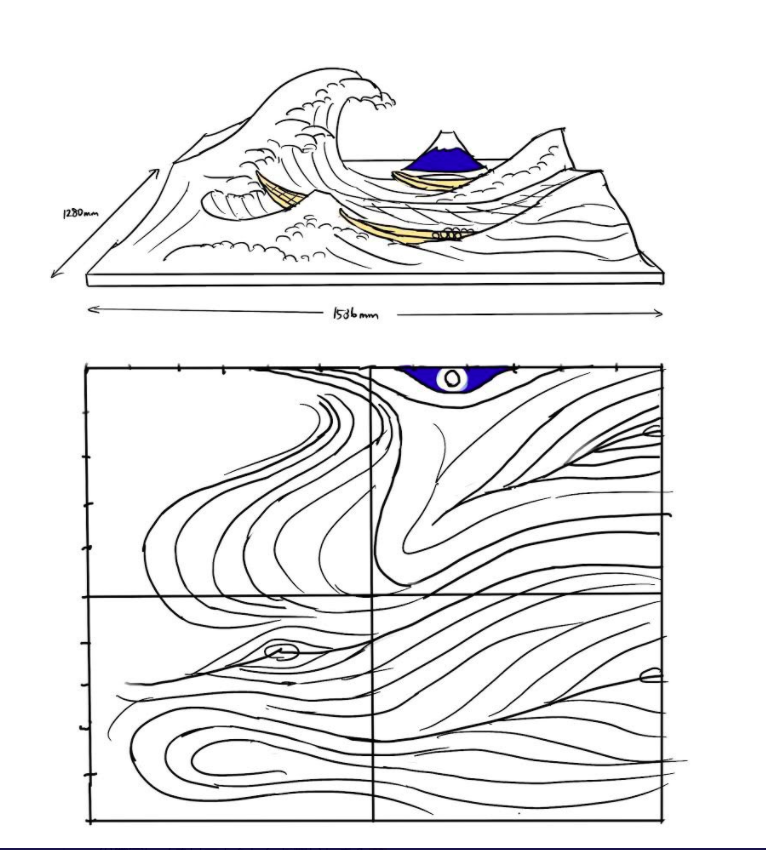

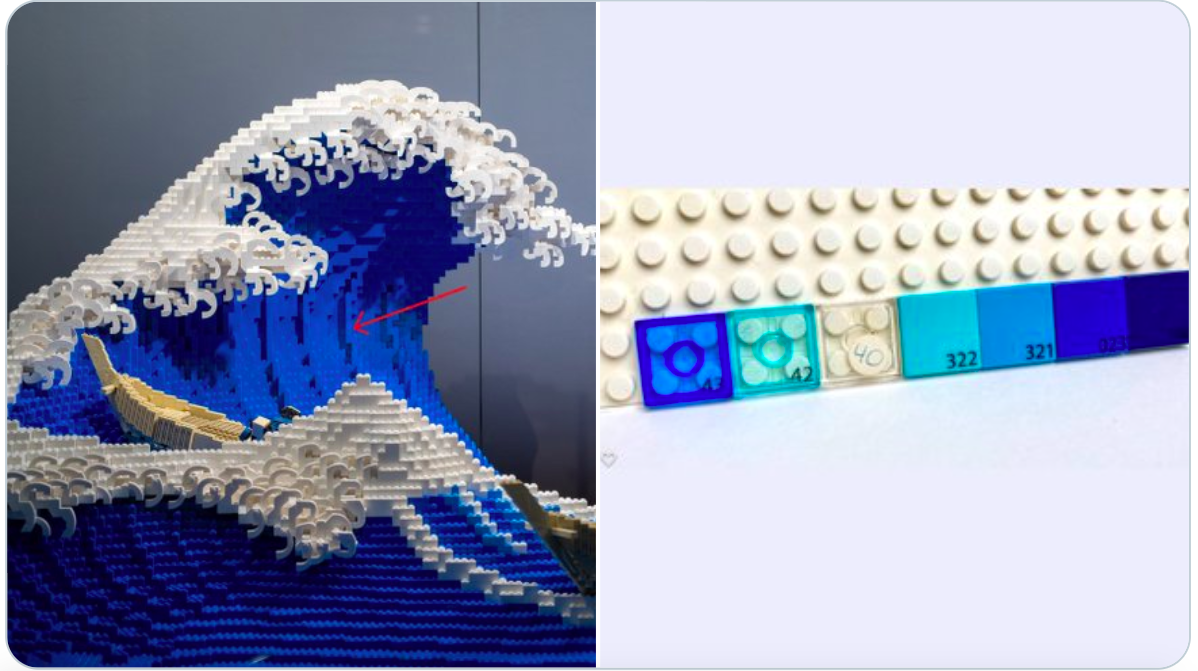

A few years ago here on Open Culture, we featured a re-creation of The Great Wave off Kanazawa made entirely out of LEGO by a serious enthusiast named Jumpei Mitsui. Though the work’s depth does come across to some extent in still photos, it bears repeating that Mitsui assembled not just a two-dimensional image, but a complete three-dimensional scene that, when viewed straight on, looks just like Hokusai’s famous woodblock print. All told, the project required 50,000 LEGO bricks, all of which you can now watch Mitsui lay down in the ten-minute time-lapse video above.

By presenting the whole construction process from a variety of angles, the video allows us to better appreciate not just the painstaking manual labor involved, but the amount of creative and technical work necessary to conceptualize the Great Wave — perhaps the foremost example of the vividly flat ukiyo‑e woodblock print style — in physical reality.

Viewers who’ve never tried their hand at large-scale LEGO building will also be surprised by the way in which Mitsui goes about building the grid-like sub-structure that undergirds what looks, in the finished product, like a sold sea of bricks.

It’s natural that Mitsui (now a “LEGO Certified Professional”) has shared the details of how he built his best-known LEGO creation on Youtube, given that it was on the same platform that he gained some of the knowledge necessary to execute it in the first place. “The brick artist observed waves on Youtube for hours, and read academic papers on waves to better understand their forms and energy,” notes The Kid Should See This, underscoring the intensity of preparation required even for what may, at first, look like a novelty project. And if the still-young Mitsui is anything like his nineteenth-century countryman, he’ll be tempted to build the Great Wave again, and even better, a few more times in the decades to come.

Related content:

Hokusai’s Iconic Print The Great Wave off Kanagawa Recreated with 50,000 LEGO Bricks

Ai Weiwei Recreates Monet’s Water Lilies Triptych Using 650,000 Lego Bricks

The Frank Lloyd Wright LEGO Set

With 9,036 Pieces, the Roman Colosseum Is the Largest LEGO Set Ever

Why Did LEGO Become a Media Empire? Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast #37

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

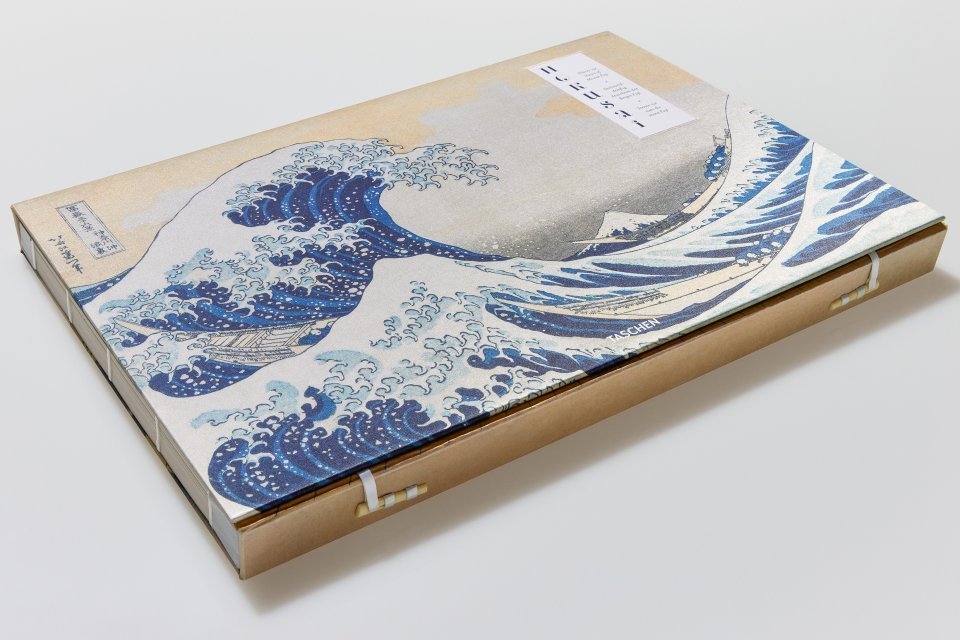

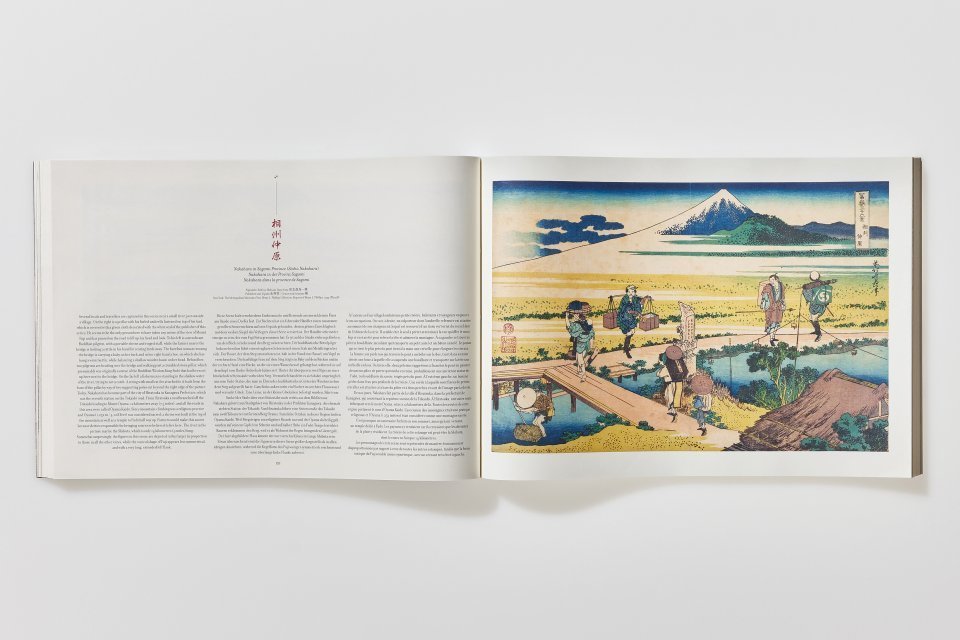

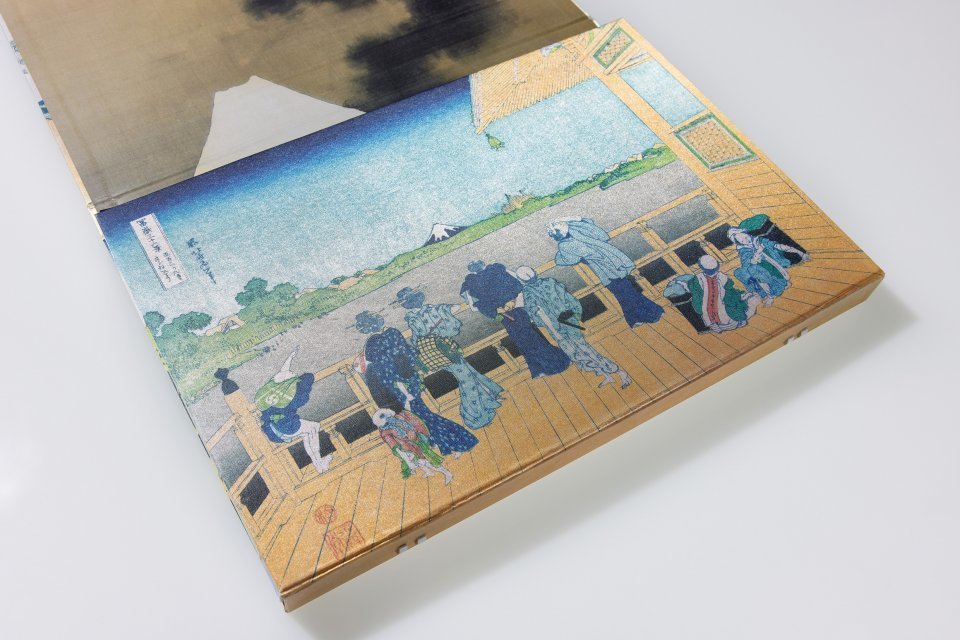

Read More...Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji: A Deluxe New Art Book Presents Hokusai’s Masterpiece, Including “The Great Wave Off Kanagawa”

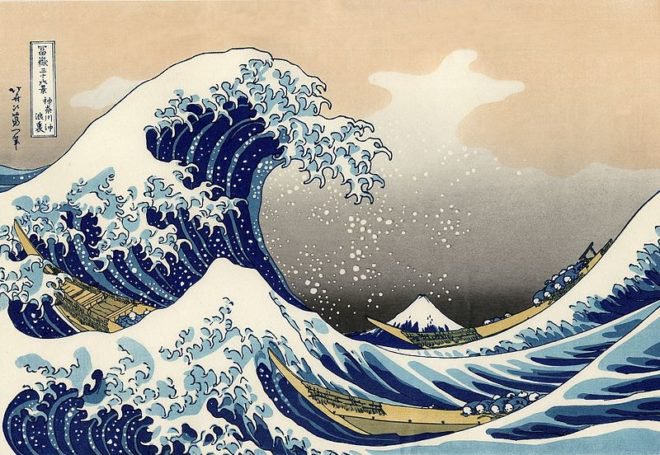

Like most Japanese masters of ukiyo‑e woodblock art, Katsushika Hokusai is best known mononymously. But he’s even better known by his work — and by one piece of work in particular, The Great Wave off Kanagawa. Even those who’ve never heard the name Hokusai have seen that print, arresting in its somehow calm turbulence, or at least they’ve seen one of its countless modern parodies and tributes (most recently, a large-scale homage in the medium of LEGO). But when he died in 1849, the prolific and long-lived artist left behind a body of work amounting to more than 30,000 paintings, sketches, prints, and illustrations (as well as a how-to-draw book).

None of those 30,000 works are quite as famous as his Great Wave off Kanagawa, but very few indeed are as ambitions as the series to which it belongs, Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji. It is that two-year project, the artistic fruit of an obsession with Fuji and its environs, that Taschen has taken as the material for their new book Hokusai: Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji.

Produced in a 224-page “XXL edition,” it gathers “the finest impressions from institutions and collections worldwide in the complete set of 46 plates alongside 114 color variations” — all sewn together, appropriately, with “Japanese binding.”

Not only does the book reproduce Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji with Taschen’s signature attention to image quality, it presents The Great Wave off Kanagawa in a way few actually see it: in context. For that most widely published of all Hokusai prints launched the series, which continued on to Fine Wind, Clear Morning, Thunderstorm Beneath the Summit, and Kajikazawa in Kai Province, that last being an image held in especially high esteem by ukiyo‑e enthusiasts. One such enthusiast, east Asian art historian Andreas Marks, has performed this book’s editing and writing, as he did with Taschen’s previous Japanese Woodblock Prints (1680–1938). Experiencing the whole of Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, more than one reader will no doubt become as transfixed by Hokusai as Hokusai was by his homeland’s most beloved mountain. You can pick up a copy of Hokusai: Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji here.

Related Content:

See Classic Japanese Woodblocks Brought Surreally to Life as Animated GIFs

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Hokusai’s Iconic Print, “The Great Wave off Kanagawa,” Recreated with 50,000 LEGO Bricks

For those with the time, skill, and drive, LEGO is the perfect medium for wildly impressive recreations of iconic structures, like the Taj Mahal, Eiffel Tower, the Titanic and now the Roman Colosseum.

But water? A wave?

And not just any wave, but Katsushika Hokusai’s celebrated 19th-century woodblock print, The Great Wave off Kanagawa.

As Open Culture’s Colin Marshall pointed out earlier, you might not know the title, but the image is instantly recognizable.

Artist Jumpei Mitsui, the world’s youngest LEGO Certified Professional, was undeterred by the thought of tackling such a dynamic and well known subject.

While other LEGO enthusiasts have created excellent facsimiles of famous artworks, doing justice to the curves and implied motion of The Great Wave seems a nearly impossible feat.

Having spent his childhood in a house by the sea, waves are a familiar presence to Mitsui. To get a better sense of how they work, he read several scientific papers and spent four hours studying wave videos on YouTube.

He made only one preparatory sketch before beginning the build, an effort that required 50,000 some LEGO pieces.

His biggest hurdle was choosing which color bricks to use in the area indicated by the red arrow in the photo below. Hokusai had taken advantage of the newly affordable Berlin blue pigment in the original.

Mitsui tweeted:

I tried a total of 7 colors including transparent parts, but in the end, I adopted the same blue color as the waves. If you use other colors, the lines will be overemphasized and unnatural, but if you use blue, the shade will be created just by adjusting the light, and the natural lines will appear nicely. It can be said that it was possible because it was made three-dimensional.

Jumpei Mitsui’s wave is now on permanent view at Osaka’s Hankyu Brick Museum.

via Spoon and Tamago and Colossal

Related Content:

The Frank Lloyd Wright Lego Set

With 9,036 Pieces, the Roman Colosseum Is the Largest Lego Set Ever

Why Did LEGO Become a Media Empire? Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast #37

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. She most recently appeared as a French Canadian bear who travels to New York City in search of food and meaning in Greg Kotis’ short film, L’Ourse. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Read More...The Evolution of The Great Wave off Kanagawa: See Four Versions That Hokusai Painted Over Nearly 40 Years

Has any Japanese woodblock print — or for that matter, any piece of Japanese art — endured as well across place and time as The Great Wave off Kanagawa? Even those of us who have never known its name, let alone those of us unsure of who made it and when, can bring it to mind it with some clarity, as sure a sign as any (along with the numerous parodies) that it taps into something deep within all of us. But though the artist behind it, 18th- and 19th-century ukiyo‑e painter Katsushika Hokusai, was undoubtedly a master of his tradition, even he didn’t conjure up The Great Wave off Kanagawa in the form we know it on the first try.

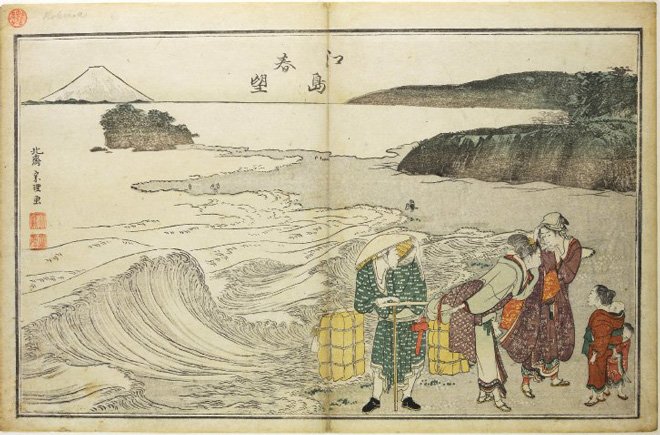

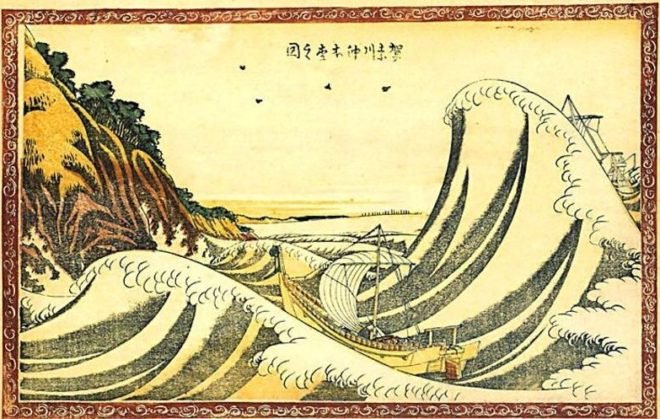

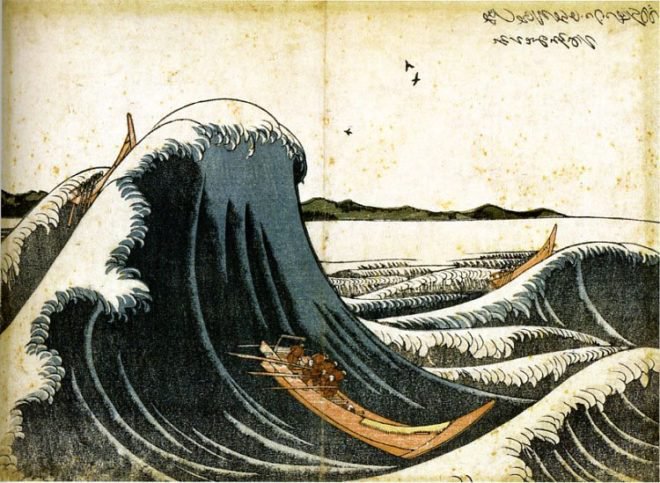

In fact, he’d been producing different versions of it for nearly forty years. On Twitter Tarin tkasasagi recently posted four versions of the Great Wave that Hokusai painted over that period. Here you see them arranged from top to bottom: the first from 1792, when he was 33; the second from 1803, when he was 44; the third from 1805, when he was 46; and the famous fourth from 1831, when he was 72.

Each time, Hokusai de-emphasizes the human presence and emphasizes the natural elements, bringing out drama from the water itself rather than from the people who regard or navigate it. In each version, too, the colors grow bolder and the lines stronger.

The skill level of a working artist — especially an artist working as hard as Hokusai — almost inevitably increases over time, and that must have something to do with these changes, though it also looks like the process of an artistic personality settling into its subject matter. “From the time I was six, I was in the habit of sketching things I saw around me,” says Hokusai himself in a widely circulated quotation. “Around the age of 50, I began to work in earnest, producing numerous designs. It was not until my 70th year, however, that I produced anything of significance.”

In the artist’s telling, only at the age of 73, after the final Great Wave, did he begin to grasp “the underlying structure of birds and animals, insects and fish, and the way trees and plants grow. Thus if I keep up my efforts, I will have even a better understanding when I was 80 and by 90 will have penetrated to the heart of things. At 100, I may reach a level of divine understanding, and if I live decades beyond that, everything I paint — dot and line — will be alive.” The fact that he didn’t make it to 100 will forever keep enthusiasts wondering what magnificence an even older Hokusai might have achieved, but even so, the body of work he managed to produce in his 88 years contains works that, like the ultimate form of The Great Wave off Kanagawa, outlived him and will outlive all of us.

Related Content:

Enter a Digital Archive of 213,000+ Beautiful Japanese Woodblock Prints

Download 2,500 Beautiful Woodblock Prints and Drawings by Japanese Masters (1600–1915)

Download Classic Japanese Wave and Ripple Designs: A Go-to Guide for Japanese Artists from 1903

Download Hundreds of 19th-Century Japanese Woodblock Prints by Masters of the Tradition

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...The Great Wave Off Kanagawa by Hokusai: An Introduction to the Iconic Japanese Woodblock Print in 17 Minutes

When woodcut artist Katsushika Hokusai made his famous print The Great Wave off Kanagawa in 1830 — part of the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji — he was 70 years old and had lived his entire life in a Japan closed off from the rest of the world. In the 19th century, however, “the rest of the world was becoming industrialized,” James Payne explains above in his Great Art Explained video, “and the Japanese were concerned about foreign invasions.” The Great Wave shows “an image of Japan fearful that the sea — which has protected its peaceful isolation for so long — would become its downfall.”

It’s also true, however, that The Great Wave would not have existed without a foreign invasion. Prussian blue, the first stable blue pigment, accidentally invented around 1705 in Berlin, arrived in the ports of Nagasaki on Dutch and Chinese ships in the 1820s. Prussian Blue would start a new artistic movement in Japan, aizuri‑e, woodcuts printed in bright, vivid blues.

“Hokusai was one of the first Japanese printmakers to boldly embrace the colour,” Hugh Davies writes at The Conversation, “a decision that would have major implications in the world of art.” When the country’s isolationist policies ended in the 1850s, “a showcase at the inaugural Japanese Pavilion elevated the artistic status of woodblock prints and a craze for their collection quickly followed.”

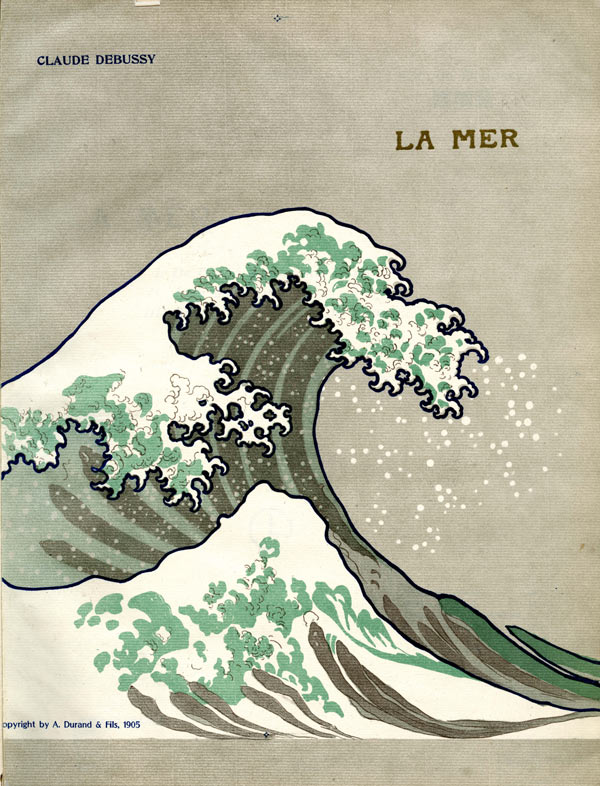

Chief among the works collected in the European and American fervor for Japanese prints were those from Hokusai, his contemporary Hiroshige, and other aizuri‑e artists. So famous was The Great Wave in the West by 1891 that French graphic artist Pierre Bonnard would satirize its stylish spray in an advertisement for champagne. A print of The Great Wave hung on Claude Debussy’s wall, and the first edition of his La Mer bore an adaptation of a detail from the print. As Michael Cirigliano writes for the Metropolitan Museum of Art:

Cultural circles throughout Europe greatly admired Hokusai’s work…. Major artists of the Impressionist movement such as Monet owned copies of Hokusai prints, and leading art critic Philippe Burty, in his 1866 Chefs-d’oeuvre des Arts industriels, even stated that Hokusai’s work maintained the elegance of Watteau, the fantasy of Goya, and the movement of Delacroix. Going one step further in his lauded comparisons, Burty wrote that Hokusai’s dexterity in brush strokes was comparable only to that of Rubens.

These comparisons are not misplaced, John-Paul Stonard explains in The Guardian: “That the Great Wave became the best known print in the west was in large part due to Hokusai’s formative experience of European art.” Not only did he absorb Prussian blue into his repertoire, but “prints from early in his career show him attempting, rather awkwardly, to apply the lesson of mathematical perspective, learnt from European prints brought into Japan by Dutch Traders.” By the time of The Great Wave, he had perfected his own synthesis of Western and Japanese art, over two decades before European painters would attempt the same in the explosion of Japanophilia of the late 19th and early 20th century.

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...An Introduction to Hokusai’s Great Wave, One of the Most Recognizable Artworks in the World

You need not be a student of Japanese Ukiyo‑e woodblock prints to recognize artist Katsushika Hokusai’s Under the Wave Off Kanagawa — or the Great Wave, as it has come to be known.

Like Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa and Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus, it’s been reproduced on all manner of improbable items and subjected to liberal reimagining — something Sarah Urist Green, describes in the above episode of her series The Art Assignment as “numerous crimes against this image perpetrated across the internet.”

Such repurposing is the ultimate compliment.

The Great Wave is so graphically indelible, anyone who co-opts it can expect it to do a lot of heavy lifting.

For those who bother looking closely enough to take in the three boatloads of fishermen struggling to escape with their lives, it’s also narratively gripping, a terrifying woodblock still from an easily imagined disaster film.

It’s also an homage to Mount Fuji, one of a series of 36.

Thousands of prints were produced in the early 1830s for the domestic tourist trade. Visitors to Mount Fuji snapped these souvenirs up for about the same price as a bowl of noodle soup.

Green, a curator and educator, points out how the water-obsessed Hokusai borrowed elements from both the Rinpa school and Western realism for the Great Wave. The latter can be seen in the use of linear perspective, a low horizon line, and Prussian blue.

An 1867 posthumous showing at the International Exhibition in Paris turned such notable artists as Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Mary Cassatt, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec into major Ukiyo‑e fans.

Without them, this iconic plunging breaker might never have spilled over onto our dorm room walls, our shower curtains, our yoga mats, t‑shirts, Doc Martens, street art, and tattoos.

Hell, there’s even a Lego set and an official Sanrio characters greeting card showing Hello Kitty nonchalantly surfing the crest in a two piece bathing suit, more interested in disporting herself than considering the sort of extreme oceanic events we can expect more of, owing to climate change.

Related Content

View 103 Discovered Drawings by Famed Japanese Woodcut Artist Katsushika Hokusai

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Read More...Get Free Drawing Lessons from Katsushika Hokusai, Who Famously Painted The Great Wave of Kanagawa: Read His How-To Book, Quick Lessons in Simplified Drawings

Even if you don’t know eighteenth and nineteenth century Japanese art, you definitely know the work of eighteenth and nineteenth century Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai — specifically his Great Wave off Kanagawa. (And if you’d like to know a little more about it, have a look at this short video from PBS’ The Art Assignment.) But if that so often reproduced, imitated, and parodied 1830s woodblock print stands for Hokusai’s oeuvre, it also obscures it, for in his long life he created not just many other works of art but works that helped, and continue to help, others create art as well.

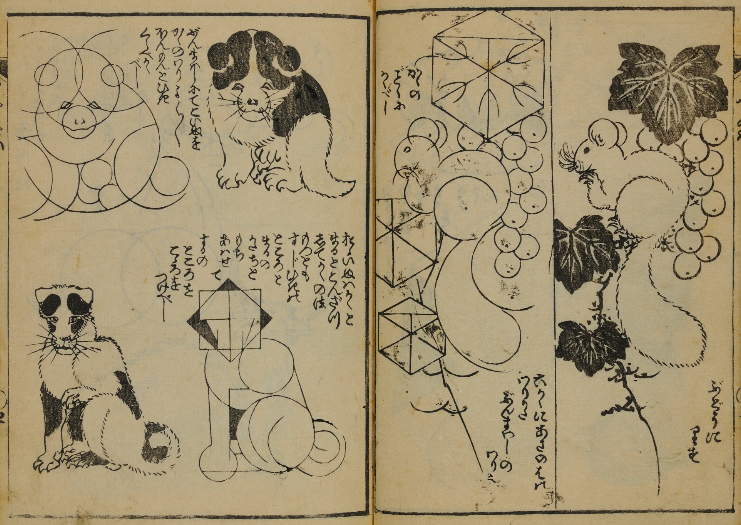

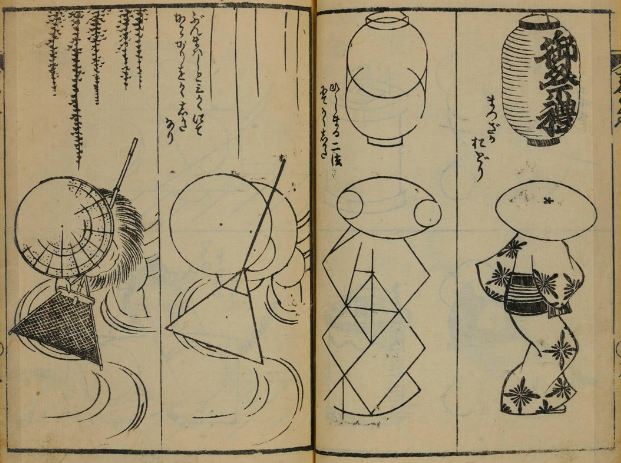

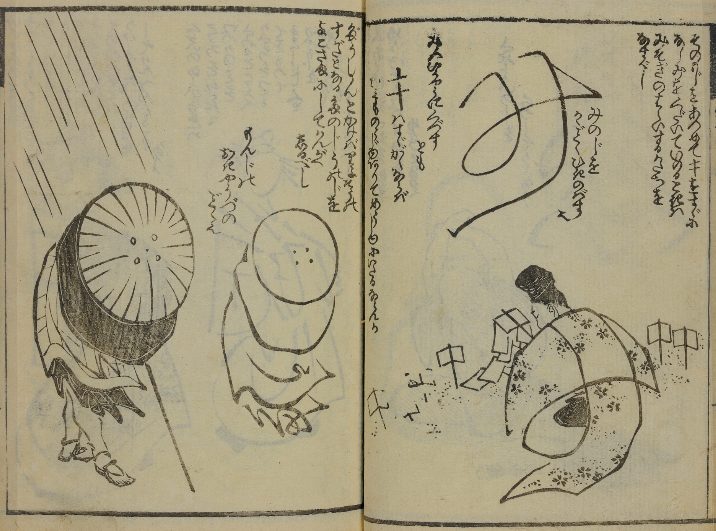

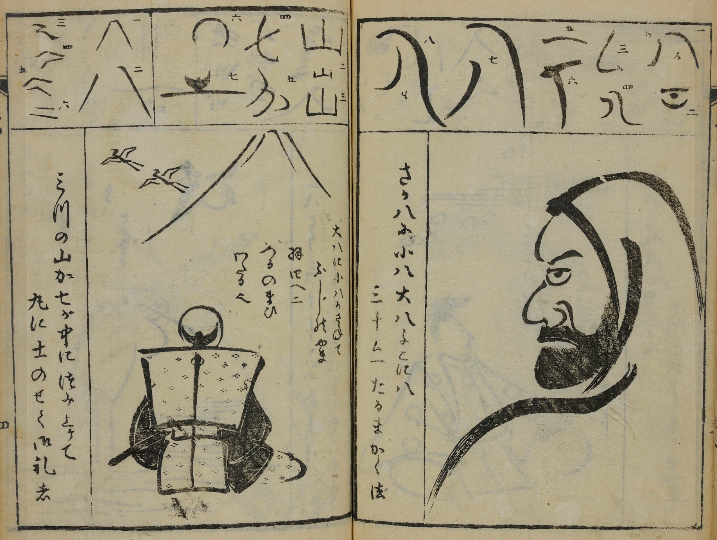

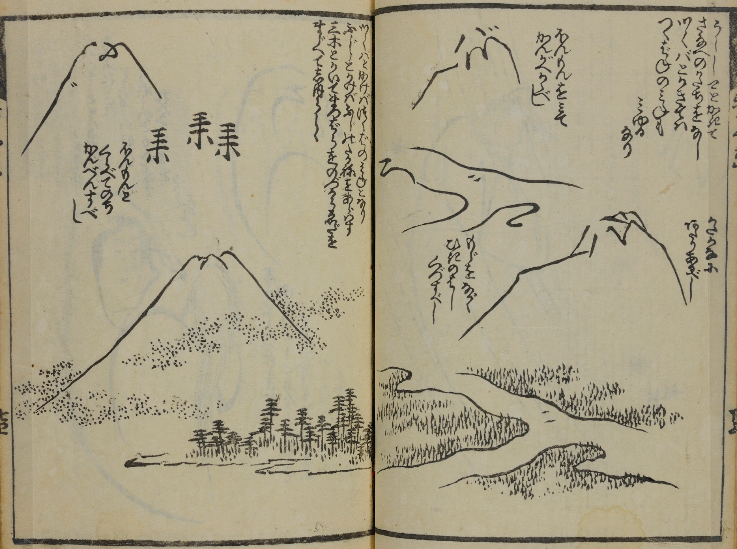

Hokusai’s bibliography, writes a Metafilter user by the name of Theodolite, includes “a little-known how-to book: 略画早指南, or Quick Lessons in Simplified Drawings, a manual in three parts. Volume I breaks every drawing down into simple geometric shapes; volume II decomposes them into fragmentary contours; and volume III neatly diagrams each stroke and the order in which they were drawn.”

Follow those links and you can read each of the books page-by-page, and not to worry if you don’t read Japanese; the artist renders his examples so clearly that the astute student can easily follow them.

Not that an understanding of Japanese wouldn’t enrich the reading experience: “Those are not all contours — they’re often characters,” notes another Mefite in the comments. “On page 4, there are drawings based on の, no, and the cranes start with ふ, fu. On page 9, the drawing of the man on the right is elaborated from み, mi. The hill on page 12 comes from 山, san, ‘mountain.’ The rocks on page 19 are from 石, ishi, ‘stone.’ ” These pages thus provide the especially astute student a way to learn Hokusai’s style of drawing and the elements of the written Japanese language at once.

In addition to the Quick Lessons books, adds Theodolite, Hokusai’s “other pedagogical works include his Drawing Methods, Quick Pictorial Dictionary, Dance Instruction Manual, and the lovely, three-color Pictures Drawn in One Stroke.” Considering the immense respect accorded to Hokusai today from all corners of the world — up to and including subtle tributes paid in major motion pictures — it surprises some to learn that he considered himself a “mere” commercial artist. But perhaps that very attitude endowed him with a relatively common touch, of the kind that enabled him to share his techniques with the reading public so openly, and so elegantly.

(via Metafilter)

Related Content:

Enter a Digital Archive of 213,000+ Beautiful Japanese Woodblock Prints

Download 2,500 Beautiful Woodblock Prints and Drawings by Japanese Masters (1600–1915)

Download Hundreds of 19th-Century Japanese Woodblock Prints by Masters of the Tradition

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Watch the Film That Invented Cinema: Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory in Lyon (1895)

The brothers Auguste and Louis Lumière are often referred to as pioneers of cinema, and their 45-second La Sortie de l’Usine Lumière à Lyon, or Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory in Lyon (1895), is often referred to as the first film. But history turns out to present a more complicated picture. As previously featured here on Open Culture, Louis Le Prince’s Roundhay Garden Scene predates the Lumière brothers’ work by six and a half years. But it is La Sortie that cinema historians regard as the more important picture, and indeed, as “the invention of movies for mass audiences.”

So writes Ryan Lattanzio at IndieWire, who goes on to explain that “the Lumière brothers were among the first filmmakers in world history, pioneering cinematic technology as well as establishing the common grammar of film.”

In an essay re-printed on Senses of Cinema, the director Haroun Farocki frames La Sortie as having established the grand subjects like regimentation and individuality with which motion pictures have dealt ever since. “For over a century cinematography had been dealing with just one single theme,” he writes. “Like a child repeating for more than a hundred years the first words it has learned to speak in order to immortalize the joy of first speech.”

Farocki also draws an analogy with “painters of the Far East, always painting the same landscape until it becomes perfect and comes to include the painter within it.” And just as Hokusai painted several different versions of his famous The Great Wave off Kanagawa, the Lumière brothers didn’t shoot just one La Sortie, but three. Though each one may look the same at first glance to the eyes of twenty-first century viewers, they’re actually distinguished by many subtle differences, including the season-reflecting attire of the workers and the number of horses drawing the carriage. And so, if we choose to credit the Lumière brothers with inventing cinema as we know it, we must also credit them with a more dubious creation, one we’ve come to know all too well in recent decades: the remake.

Related content:

Watch the Films of the Lumière Brothers & the Birth of Cinema (1895)

The History of the Movie Camera in Four Minutes: From the Lumière Brothers to Google Glass

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...

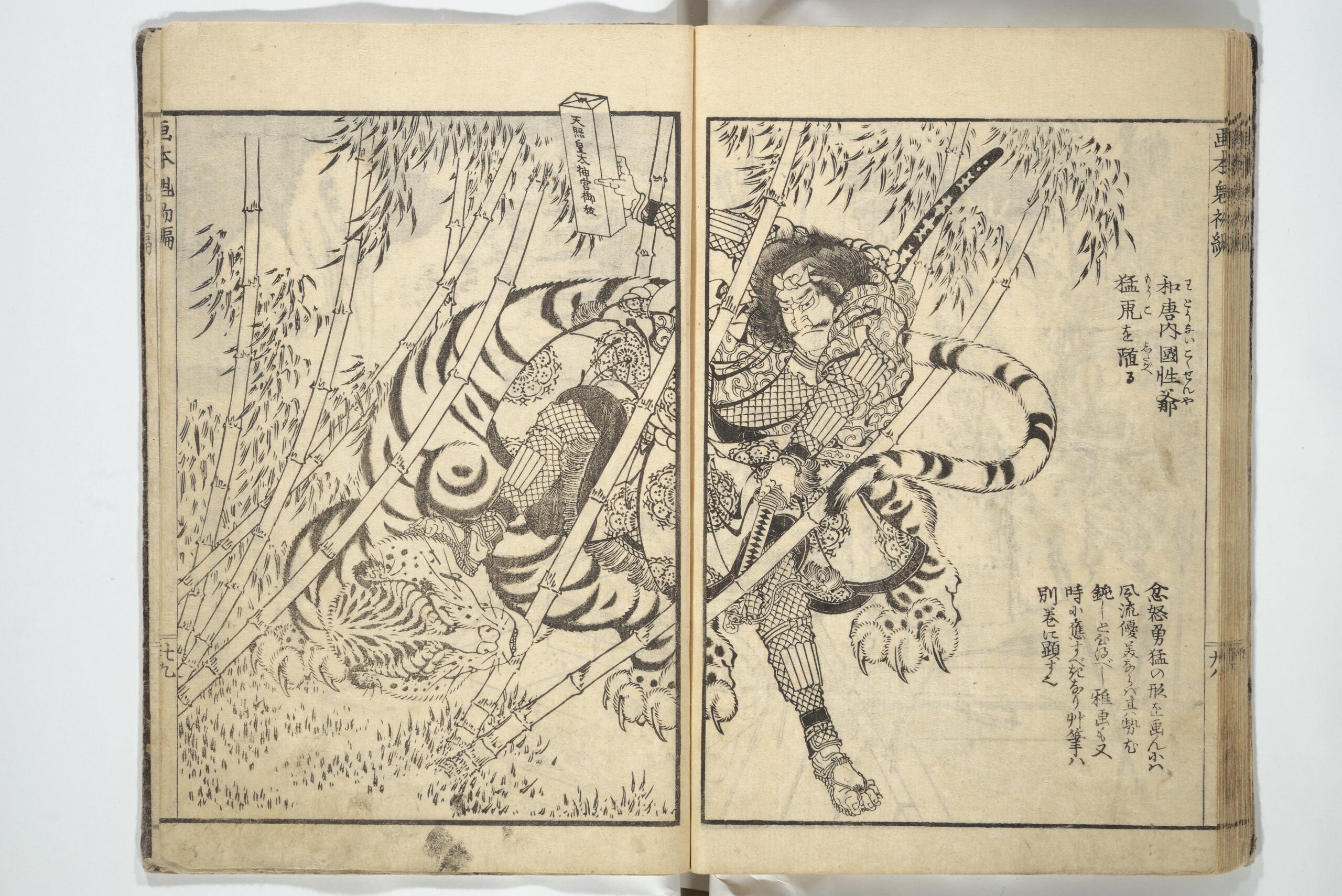

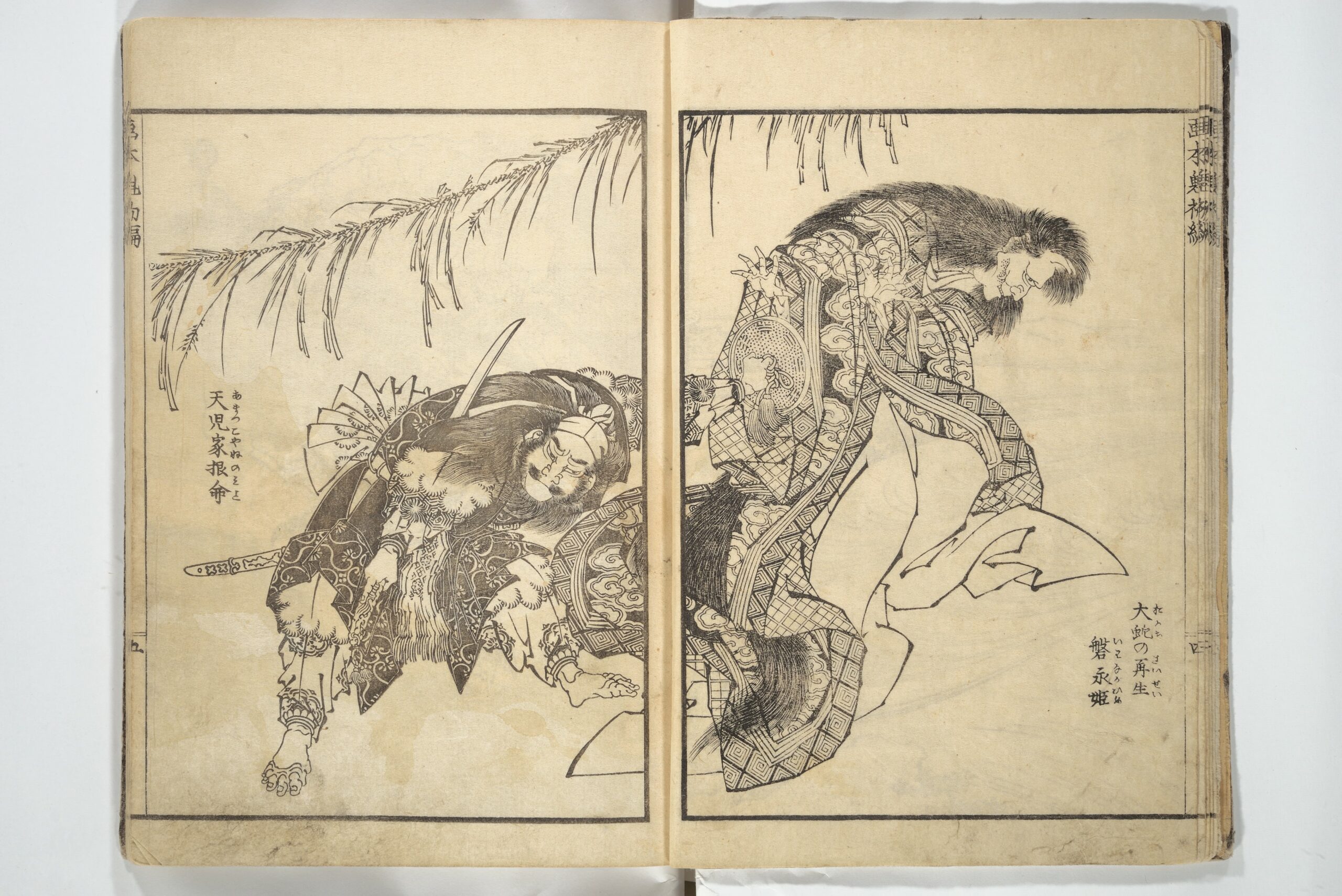

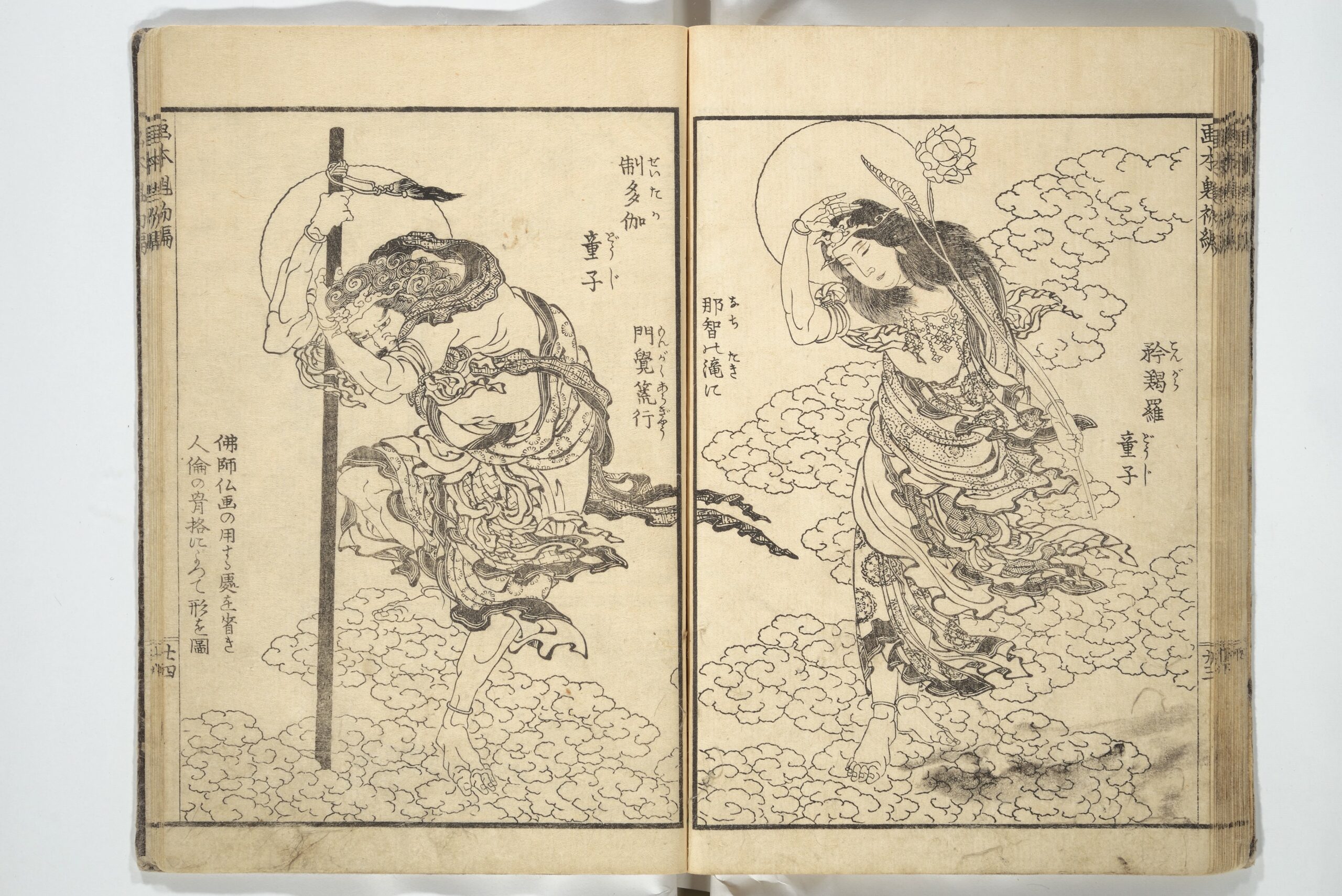

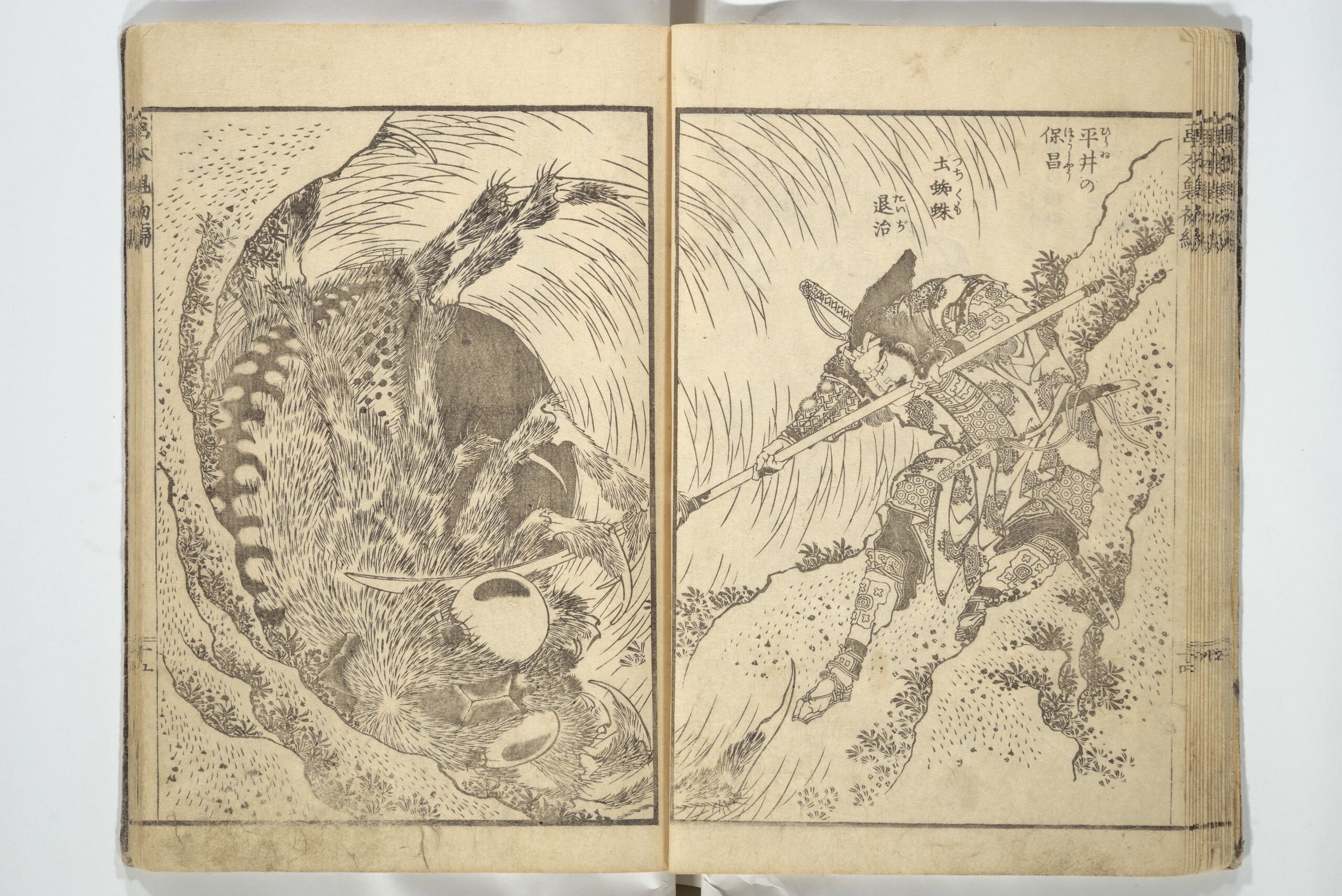

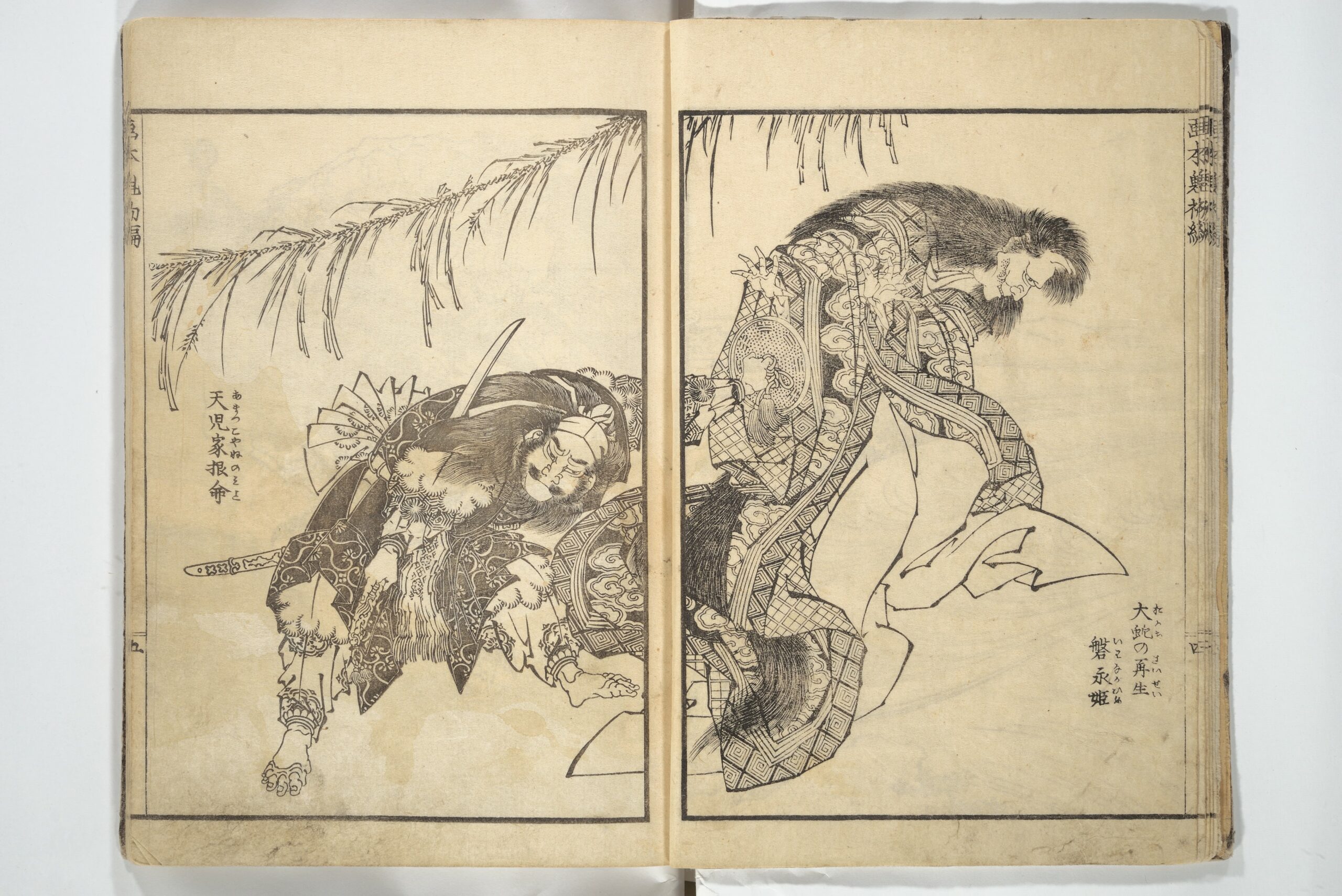

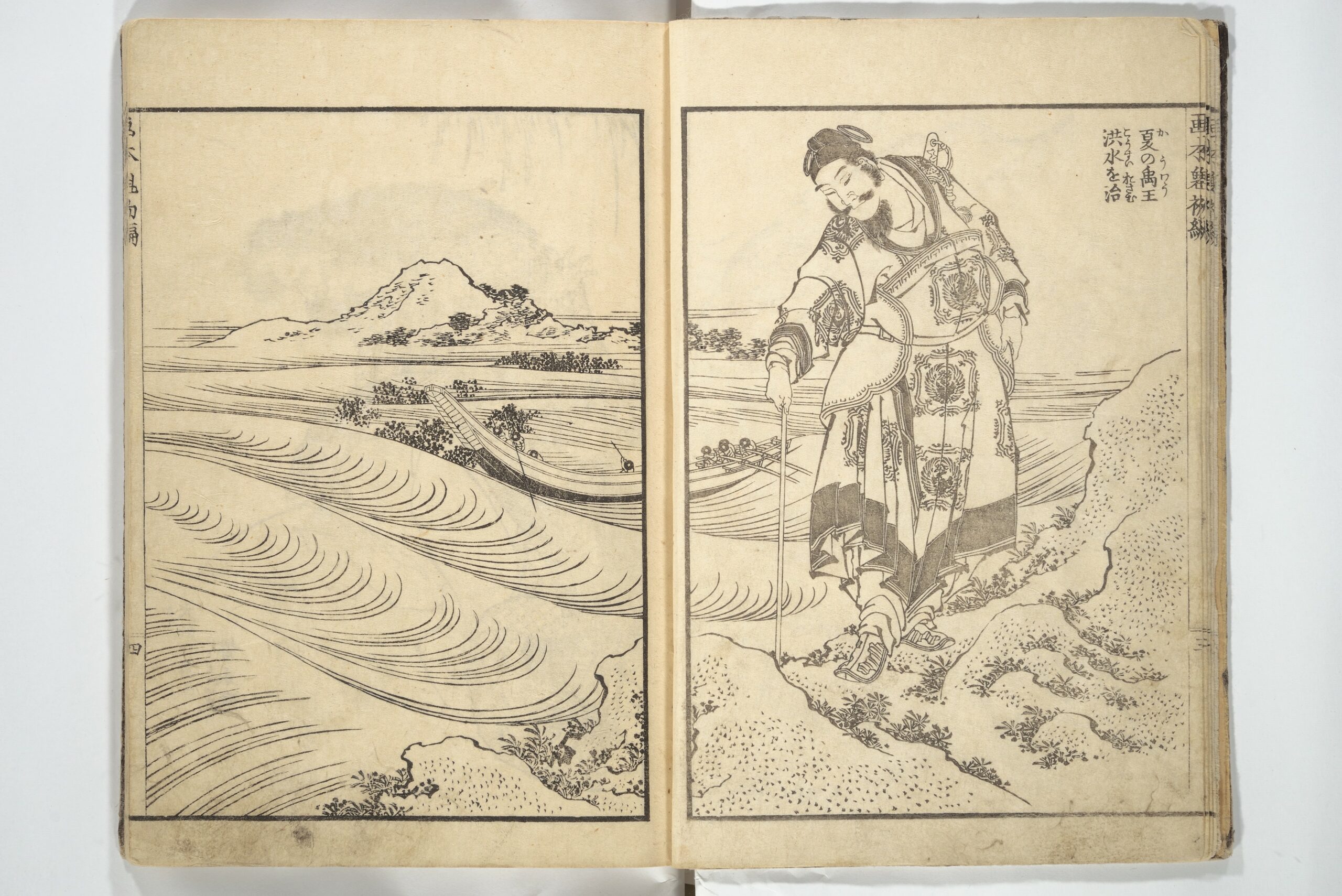

Hokusai’s Action-Packed Illustrations of Japanese & Chinese Warriors (1836)

Katsushika Hokusai created his best-known woodblock print The Great Wave Off Kanagawa — or rather he finished its definitive version — when he was in his early sixties. That may sound somewhat late in the day by the standards of visual artists, but as Hokusai himself saw it, he was just getting started. At the Public Domain Review, Koto Sadamura quotes the artist’s own words, as included in the book One Hundred Views of Mt. Fuji: “Until the age of seventy, nothing I drew was worthy of notice. At seventy-three years, I was somewhat able to fathom the growth of plants and trees, and the structure of birds, animals, insects and fish.”

Sadamura goes on to introduce a different, lesser-known, and even later series of Hokusai’s artworks: “Wakan ehon sakigake, which assembles images of famous Japanese and Chinese warriors, both historical and legendary. The Japanese term sakigake in the title signifies outstanding figures or leaders (Wakan means Japanese and Chinese, and ehon is a picture book).”

Like many a hardworking ukiyo‑e artist, Hokusai created these images to order, his publisher having asked him to “fill three volumes with ‘wisdom’ [chi], ‘humanity’ [jin] and ‘bravery’ [yū], using examples of widely celebrated mighty heroes as reminders of military arts even in times of peace.”

The results, which you can see both at the Public Domain Review and the site of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, clearly fulfill their mandate of revivifying from a glorious past, real or imagined. But they also exude a certain aesthetic familiarity even today: in Hokusai’s depiction of the Heian-period warrior Hirai Yasumasa “subduing a monster spider,” for example, “lines in the background trace the motion of the gigantic arachnid as it tumbles and its sickle-like legs flail in the air, emphasizing the movement and force in a way that resonates with the visual effects of modern manga.”

All the more surprising, then, not just that the Wakan ehon sakigake (or at least two of its planned three volumes) are now 187 years old, but also that Hokusai himself was seventy-six at the time. “Each tiny leaf growing on the rocks and each textural mark on the ragged surface is animated, filling the picture with vibrating energy,” Sadamura writes. “Every single strand of hair is charged with life.”

But the master foresaw greater achievements ahead, only after attaining the experience that would attend an even more advanced age: “At one hundred and ten, every dot and every stroke will be as though alive.” Alas, Hokusai died in 1849, at the tender age of 88, leaving us to imagine the level of artistry he might have attained had he reached maturity.

Related content:

View 103 Discovered Drawings by Famed Japanese Woodcut Artist Katsushika Hokusai

Hand-Colored 1860s Photographs Reveal the Last Days of Samurai Japan

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...A Collection of Hokusai’s Drawings Are Being Carved Onto Woodblocks & Printed for the First Time Ever

If you know anything about the ukiyo‑e masters of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Japan like Kitagawa Utamaro, Utagawa Hiroshige, and Katsushika Hokusai, you know that they became renowned through woodblock prints. But in almost all cases, a woodblock print begins in another medium: the medium of the drawing, where the artist works out the image before committing (or having it committed) to a block of wood for printing. This process, as Tokyo-based Canadian printmaker David Bull explains in the video above, entailed the destruction of the original drawing — or at least it did a couple of centuries ago, before the advent of copy machines, let alone high-resolution digital scanners.

Our time has not only these technologically advanced tools, but also, as previously featured here on Open Culture, a wealth of rediscovered drawings by Hokusai himself. “The existence of these exquisite small drawings had been forgotten,” says the site of the British Museum. “Last publicly recorded at a Parisian auction in 1948, they are said to have been in a private collection in France before resurfacing in 2019.”

Having acquired the 103 images that constitute this Great Picture Book of Everything, the British Museum has entered into a collaboration with Bull, whose workshop Mokuhankan is taking a selection of these drawings — never printed in Hokusai’s day — and carving them into woodblocks for the first time ever.

You can enjoy this project, called Hokusai Reborn, by following its progress on Bull’s Youtube channel; the first two episodes of the series appear just above. You can also purchase a subscription to receive copies of the actual prints now being made from Hokusai’s drawings at Mokuhankan. “The prints will be 13.5 x 18.5 cm in format (slightly larger than 5 x 7 inches),” says the page at the studio’s site with more information on that, “and will be made on a thin version of our usual hosho washi, made in the workshop of Iwano Ichibei,” one of Japan’s officially designated Living National Treasures. This sales model is in keeping with the commercial model of ukiyo‑e in the Edo period of the seventeenth through the nineteenth century, when a burgeoning merchant class formed a robust customer base for its artisans. Here we have an unexpected opportunity to become one of those customers — and, perhaps, to own the next Great Wave Off Kanagawa.

via Metafilter

Related content:

View 103 Discovered Drawings by Famed Japanese Woodcut Artist Katsushika Hokusai

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...