By the end of 1960, Marilyn Monroe was coming apart.

She spent much of that year shooting what would be her final completed movie – The Misfits (see a still from the trailer above). Arthur Miller penned the film, which is about a beautiful, fragile woman who falls in love with a much older man. The script was pretty clearly based on his own troubled marriage with Monroe. The production was by all accounts spectacularly punishing. Shot in the deserts of Nevada, the temperature on set would regularly climb north of 100 degrees. Director John Huston spent much of the shoot ragingly drunk. Star Clark Gable dropped dead from a heart attack less than a week after production wrapped. And Monroe watched as her husband, who was on set, fell in love with photographer Inge Morath. Never one blessed with confidence or a thick skin, Monroe retreated into a daze of prescription drugs. Monroe and Miller announced their divorce on November 11, 1960.

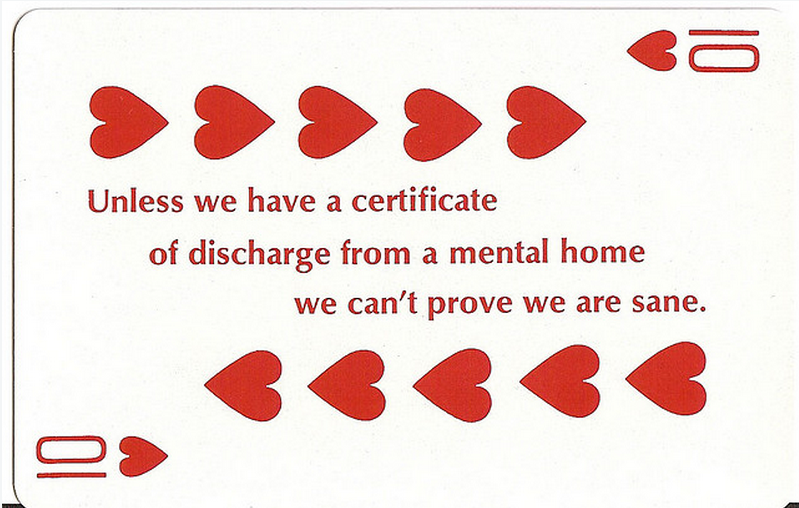

A few months later, the emotionally exhausted movie star was committed by her psychoanalyst Dr. Marianne Kris to the Payne Whitney Psychiatric Clinic in New York. Monroe thought she was going in for a rest cure. Instead, she was escorted to a padded cell. The four days she spent in the psych ward proved to be among the most distressing of her life.

In a riveting 6‑page letter to her other shrink, Dr. Ralph Greenson, written soon after her release, she detailed her terrifying experience.

There was no empathy at Payne-Whitney — it had a very bad effect — they asked me after putting me in a “cell” (I mean cement blocks and all) for very disturbed depressed patients (except I felt I was in some kind of prison for a crime I hadn’t committed. The inhumanity there I found archaic. They asked me why I wasn’t happy there (everything was under lock and key; things like electric lights, dresser drawers, bathrooms, closets, bars concealed on the windows — the doors have windows so patients can be visible all the time, also, the violence and markings still remain on the walls from former patients). I answered: “Well, I’d have to be nuts if I like it here.”

Monroe quickly became desperate.

I sat on the bed trying to figure if I was given this situation in an acting improvisation what would I do. So I figured, it’s a squeaky wheel that gets the grease. I admit it was a loud squeak but I got the idea from a movie I made once called “Don’t Bother to Knock”. I picked up a light-weight chair and slammed it, and it was hard to do because I had never broken anything in my life — against the glass intentionally. It took a lot of banging to get even a small piece of glass — so I went over with the glass concealed in my hand and sat quietly on the bed waiting for them to come in. They did, and I said to them “If you are going to treat me like a nut I’ll act like a nut”. I admit the next thing is corny but I really did it in the movie except it was with a razor blade. I indicated if they didn’t let me out I would harm myself — the furthest thing from my mind at that moment since you know Dr. Greenson I’m an actress and would never intentionally mark or mar myself. I’m just that vain.

During her four days there, she was subjected to forced baths and a complete loss of privacy and personal freedom. The more she sobbed and resisted, the more the doctors there thought she might actually be psychotic. Monroe’s second husband, Joe DiMaggio, rescued her by getting her released early, over the objections of the staff.

You can read the full letter (where she also talks about reading the letters of Sigmund Freud) over at Letters of Note. And while there, make sure you pick up a copy of the very elegant Letters of Note book.

Related Content:

The 430 Books in Marilyn Monroe’s Library: How Many Have You Read?

Marilyn Monroe Reads Joyce’s Ulysses at the Playground (1955)

Marilyn Monroe Reads Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass (1952)

Marilyn Monroe Explains Relativity to Albert Einstein (in a Nicolas Roeg Movie)

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow. And check out his blog Veeptopus, featuring lots of pictures of vice presidents with octopuses on their heads. The Veeptopus store is here.