Image via YouTube, 1959 interview with Mike Wallace

I recently happened upon the Modern Library’s “100 Best Novels” list and noticed something interesting. The list divides into two columns—the “Board’s List” on the left and “Reader’s List” on the right. The “Board’s List” contains in its top ten such expected “great books” as Joyce’s Ulysses (#1) and William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury (#6). These are indeed worthy titles, but not the most accessible of books, to be sure, though Ulysses does appear at number eleven on the “Reader’s List.” At the very top of that more popular ranking, however, is a book the literati could not find more worthy of contempt: Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged. Just below it is Rand’s The Fountainhead, and at numbers seven and eight, respectively, her Anthem and We the Living. (Also in the top ten on the “Reader’s List,” three novels by L. Ron Hubbard.)

One obvious takeaway… masses of ordinary people really like Ayn Rand. Which is odd, because Ayn Rand seemed to positively hate the masses of ordinary people. As Michael O’Donnell writes in Washington Monthly, “Rand… lived a life of contempt: for people, for ideas, for government, and for the very concept of human kindness.”

Perhaps her most sympathetic reader, economist Ludwig von Mises, summed up the overarching theme of her life’s work in one very tidy sentence: “You have the courage to tell the masses what no politician told them: you are inferior and all the improvements in your conditions which you simply take for granted you owe to the effort of men who are better than you.” This is apparently a message that a great many people are eager to hear. (And if any fiction is “message driven,” it is Rand’s.)

But imagine, if you will, that you are not a reader of Ayn Rand, but a family member. Not by blood, but marriage, but connected, nonetheless. You are Ayn Rand’s niece—Rand’s husband Frank O’Connor’s sister’s daughter, to be precise. Your name is Connie Papurt, you are 17, and you have written Auntie Ayn to ask for $25 for a new dress. Have you done this simply to be cheeky? You do know, Connie, how deeply your Aunt Ayn despises moochers, do you not? No matter—we have neither Connie’s letter, nor a window into her motivations. We do have, however, Rand’s replies, plural, from May 22, 1949, then again—in response to Connie’s follow-up—from June 4 of that same year. The initial request prompted some earnest sermonizing from Rand on the value of hard work, and of being a “self-respecting, self-supporting, responsible, capitalistic person.” Etcetera.

Now, to Rand’s credit, the first reply letter contains some common sense advice, and describes some situations in which other close connections apparently took advantage of her generosity. She seems to have cause for leeriness, as, granted, do we all in these situations. Borrowing from family is very often a tricky business. As was her wont, however, Rand seized upon the occasion not only to dispense wisdom on personal responsibility, but also to moralize on the worthlessness of people who fail her test of character. As The Toast comments, the letter is “30% very good advice, 50% unnecessary yelling, and 20% nonsense.” First, Rand lays out for Connie an installment plan:

Here are my conditions: If I send you the $25, I will give you a year to repay it. I will give you six months after your graduation to get settled in a job. Then, you will start repaying the money in installments: you will send me $5 on January 15, 1950, and $4 on the 15th of every month after that; the last installment will be on June 15, 1950—and that will repay the total.

Are you willing to do that?

Notice, Rand assesses no interest—a kindness, indeed. And yet,

I want you to understand right now that I will not accept any excuse—except a serious illness. If you become ill, then I will give you an extension of time—but for no other reason. If, when the debt becomes due, you tell me that you can’t pay me because you needed a new pair of shoes or a new coat or you gave the money to somebody in the family who needed it more than I do—then I will consider you as an embezzler. No, I won’t send a policeman after you, but I will write you off as a rotten person and I will never speak or write to you again.

According to her 2012 obituary, Connie went on to became a local Cleveland actress and nurse, a person “dedicated to making the lives of others better.” According to her aunt, she should have nothing better to do—for anyone—but to pay back her debt, should she wish to remain in the good graces of the great Objectivist. We do not know if Connie accepted the terms, but she apparently wrote back in such a way as to leave quite an impression on Rand, whose June 4 reply is “damn charming!”

I must tell you that I was very impressed with the intelligent attitude of your letter. If you really understood, all by yourself, that my long lecture to you was a sign of real interest on my part, much more so than if I had sent you a check with some hypocritical gush note, and if you understood that my letter was intended to treat you as an equal—then you have just the kind of mind that can achieve anything you choose to achieve in life.

The letter goes on in very kindly, even sentimental, terms. In fact, it may convince you that O’Donnell is dead wrong to single out contempt as Rand’s defining quality. And yet, he argues, her biographers show that “she happily accepted help from others while denouncing altruistic kindness” (and those who accept it), espousing “an individualism so extreme that it does not merely ignore others, but actually spits in their faces.” While Connie managed to escape her wrath, such as it was, most others, through their own failings of true capitalistic character or the cruelty of circumstances beyond their control, did not.

Read both of Rand’s letters here.

via The Toast

Related Content:

Ayn Rand Helped the FBI Identify It’s A Wonderful Life as Communist Propaganda

In Her Final Speech, Ayn Rand Denounces Ronald Reagan, the Moral Majority & Anti-Choicers (1981)

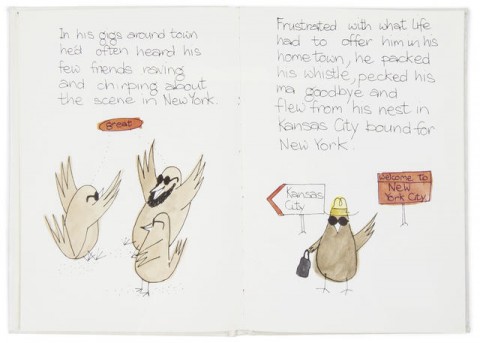

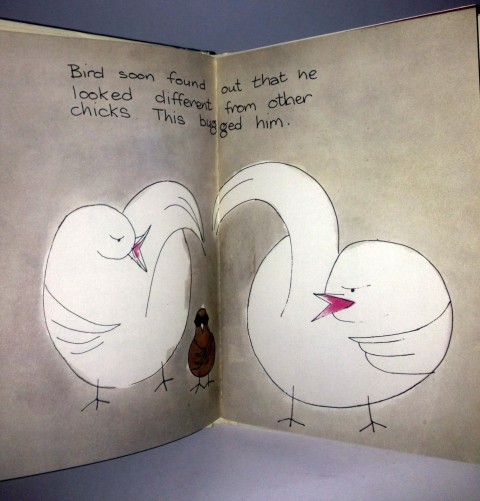

A Free Cartoon Biography of Ayn Rand: Her Life & Thought

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness