The lists are in. By overwhelming consensus, the buzzword of 2014 was “vape.” Apparently, that’s the verb that enables you to smoke an e‑cig. Left to its own devices, my computer will still autocorrect 2014’s biggest word to “cape,” but that could change.

Hopefully not.

Hopefully, 2015 will yield a buzzword more piquant than “vape.”

With luck, a razor-witted teen is already on the case, but just in case, let’s hedge our bets. Let’s go spelunking in an era when buzzwords were cool, but adult…insouciant, yet substantive.

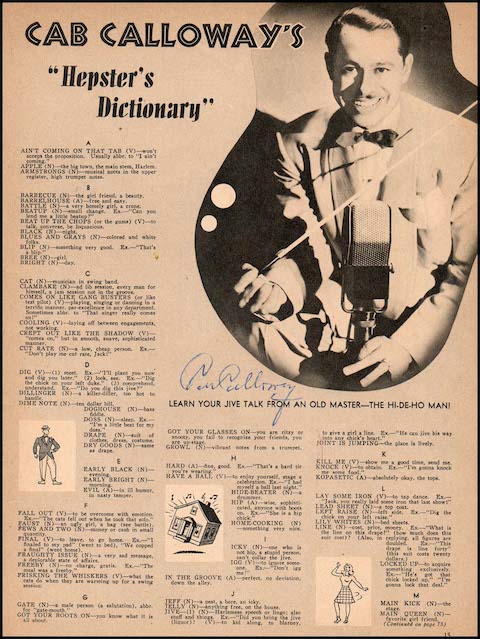

Lead us, Cab Calloway!

The charismatic bandleader not only had a way with words, his love of them led him to compile a “Hepster’s Dictionary” of Harlem musician slang circa 1938. It featured 200 expressions used by the “hep cats” when they talk their “jive” in the clubs on Lenox Avenue. It was also apparently the first dictionary authored by an African-American.

If only every amateur lexicographer were foxy enough to set his or her definitions to music, and creep them out like the shadow, as Calloway does above. The complete list is below.

What a blip!

By my calculation, we’ve got eleven months to identify a choice candidate, resurrect it, and integrate it into everyday speech. With luck some fine dinner whose star is on the rise will beef our word in public, preferably during a scandalous, much analyzed performance.

It’s immaterial which one we pick. Gammin’? Jeff? Hincty? Fruiting? Whatever you choose, I’m in. Let’s blow their wigs.

Bust your conks in the comments section. I’m ready.

HEPSTER’S DICTIONARY

A hummer (n.) — exceptionally good. Ex., “Man, that boy is a hummer.”

Ain’t coming on that tab (v.) — won’t accept the proposition. Usually abbr. to “I ain’t coming.”

Alligator (n.) — jitterbug.

Apple (n.) — the big town, the main stem, Harlem.

Armstrongs (n.) — musical notes in the upper register, high trumpet notes.

Barbecue (n.) — the girl friend, a beauty

Barrelhouse (adj.) — free and easy.

Battle (n.) — a very homely girl, a crone.

Beat (adj.) — (1) tired, exhausted. Ex., “You look beat” or “I feel beat.” (2) lacking anything. Ex, “I am beat for my cash”, “I am beat to my socks” (lacking everything).

Beat it out (v.) — play it hot, emphasize the rhythym.

Beat up (adj.) — sad, uncomplimentary, tired.

Beat up the chops (or the gums) (v.) — to talk, converse, be loquacious.

Beef (v.) — to say, to state. Ex., “He beefed to me that, etc.”

Bible (n.) — the gospel truth. Ex., “It’s the bible!”

Black (n.) — night.

Black and tan (n.) — dark and light colored folks. Not colored and white folks as erroneously assumed.

Blew their wigs (adj.) — excited with enthusiasm, gone crazy.

Blip (n.) — something very good. Ex., “That’s a blip”; “She’s a blip.”

Blow the top (v.) — to be overcome with emotion (delight). Ex., “You’ll blow your top when you hear this one.”

Boogie-woogie (n.) — harmony with accented bass.

Boot (v.) — to give. Ex., “Boot me that glove.”

Break it up (v.) — to win applause, to stop the show.

Bree (n.) — girl.

Bright (n.) — day.

Brightnin’ (n.) — daybreak.

Bring down ((1) n. (2) v.) — (1) something depressing. Ex., “That’s a bring down.” (2) Ex., “That brings me down.”

Buddy ghee (n.) — fellow.

Bust your conk (v.) — apply yourself diligently, break your neck.

Canary (n.) — girl vocalist.

Capped (v.) — outdone, surpassed.

Cat (n.) — musician in swing band.

Chick (n.) — girl.

Chime (n.) — hour. Ex., “I got in at six chimes.”

Clambake (n.) — ad lib session, every man for himself, a jam session not in the groove.

Chirp (n.) — female singer.

Cogs (n.) — sun glasses.

Collar (v.) — to get, to obtain, to comprehend. Ex., “I gotta collar me some food”; “Do you collar this jive?”

Come again (v.) — try it over, do better than you are doing, I don’t understand you.

Comes on like gangbusters (or like test pilot) (v.) — plays, sings, or dances in a terrific manner, par excellence in any department. Sometimes abbr. to “That singer really comes on!”

Cop (v.) — to get, to obtain (see collar; knock).

Corny (adj.) — old-fashioned, stale.

Creeps out like the shadow (v.) — “comes on,” but in smooth, suave, sophisticated manner.

Crumb crushers (n.) — teeth.

Cubby (n.) — room, flat, home.

Cups (n.) — sleep. Ex., “I gotta catch some cups.”

Cut out (v.) — to leave, to depart. Ex., “It’s time to cut out”; “I cut out from the joint in early bright.”

Cut rate (n.) — a low, cheap person. Ex., “Don’t play me cut rate, Jack!”

Dicty (adj.) — high-class, nifty, smart.

Dig (v.) — (1) meet. Ex., “I’ll plant you now and dig you later.” (2) look, see. Ex., “Dig the chick on your left duke.” (3) comprehend, understand. Ex., “Do you dig this jive?”

Dim (n.) — evening.

Dime note (n.) — ten-dollar bill.

Doghouse (n.) — bass fiddle.

Domi (n.) — ordinary place to live in. Ex., “I live in a righteous dome.”

Doss (n.) — sleep. Ex., “I’m a little beat for my doss.”

Down with it (adj.) — through with it.

Drape (n.) — suit of clothes, dress, costume.

Dreamers (n.) — bed covers, blankets.

Dry-goods (n.) — same as drape.

Duke (n.) — hand, mitt.

Dutchess (n.) — girl.

Early black (n.) — evening

Early bright (n.) — morning.

Evil (adj.) — in ill humor, in a nasty temper.

Fall out (v.) — to be overcome with emotion. Ex., “The cats fell out when he took that solo.”

Fews and two (n.) — money or cash in small quatity.

Final (v.) — to leave, to go home. Ex., “I finaled to my pad” (went to bed); “We copped a final” (went home).

Fine dinner (n.) — a good-looking girl.

Focus (v.) — to look, to see.

Foxy (v.) — shrewd.

Frame (n.) — the body.

Fraughty issue (n.) — a very sad message, a deplorable state of affairs.

Freeby (n.) — no charge, gratis. Ex., “The meal was a freeby.”

Frisking the whiskers (v.) — what the cats do when they are warming up for a swing session.

Frolic pad (n.) — place of entertainment, theater, nightclub.

Fromby (adj.) — a frompy queen is a battle or faust.

Front (n.) — a suit of clothes.

Fruiting (v.) — fickle, fooling around with no particular object.

Fry (v.) — to go to get hair straightened.

Gabriels (n.) — trumpet players.

Gammin’ (adj.) — showing off, flirtatious.

Gasser (n, adj.) — sensational. Ex., “When it comes to dancing, she’s a gasser.”

Gate (n.) — a male person (a salutation), abbr. for “gate-mouth.”

Get in there (exclamation.) — go to work, get busy, make it hot, give all you’ve got.

Gimme some skin (v.) — shake hands.

Glims (n.) — the eyes.

Got your boots on — you know what it is all about, you are a hep cat, you are wise.

Got your glasses on — you are ritzy or snooty, you fail to recognize your friends, you are up-stage.

Gravy (n.) — profits.

Grease (v.) — to eat.

Groovy (adj.) — fine. Ex., “I feel groovy.”

Ground grippers (n.) — new shoes.

Growl (n.) — vibrant notes from a trumpet.

Gut-bucket (adj.) — low-down music.

Guzzlin’ foam (v.) — drinking beer.

Hard (adj.) — fine, good. Ex., “That’s a hard tie you’re wearing.”

Hard spiel (n.) — interesting line of talk.

Have a ball (v.) — to enjoy yourself, stage a celebration. Ex., “I had myself a ball last night.”

Hep cat (n.) — a guy who knows all the answers, understands jive.

Hide-beater (n.) — a drummer (see skin-beater).

Hincty (adj.) — conceited, snooty.

Hip (adj.) — wise, sophisticated, anyone with boots on. Ex., “She’s a hip chick.”

Home-cooking (n.) — something very dinner (see fine dinner).

Hot (adj.) — musically torrid; before swing, tunes were hot or bands were hot.

Hype (n, v.) — build up for a loan, wooing a girl, persuasive talk.

Icky (n.) — one who is not hip, a stupid person, can’t collar the jive.

Igg (v.) — to ignore someone. Ex., “Don’t igg me!)

In the groove (adj.) — perfect, no deviation, down the alley.

Jack (n.) — name for all male friends (see gate; pops).

Jam ((1)n, (2)v.) — (1) improvised swing music. Ex., “That’s swell jam.” (2) to play such music. Ex., “That cat surely can jam.”

Jeff (n.) — a pest, a bore, an icky.

Jelly (n.) — anything free, on the house.

Jitterbug (n.) — a swing fan.

Jive (n.) — Harlemese speech.

Joint is jumping — the place is lively, the club is leaping with fun.

Jumped in port (v.) — arrived in town.

Kick (n.) — a pocket. Ex., “I’ve got five bucks in my kick.”

Kill me (v.) — show me a good time, send me.

Killer-diller (n.) — a great thrill.

Knock (v.) — give. Ex., “Knock me a kiss.”

Kopasetic (adj.) — absolutely okay, the tops.

Lamp (v.) — to see, to look at.

Land o’darkness (n.) — Harlem.

Lane (n.) — a male, usually a nonprofessional.

Latch on (v.) — grab, take hold, get wise to.

Lay some iron (v.) — to tap dance. Ex., “Jack, you really laid some iron that last show!”

Lay your racket (v.) — to jive, to sell an idea, to promote a proposition.

Lead sheet (n.) — a topcoat.

Left raise (n.) — left side. Ex., “Dig the chick on your left raise.”

Licking the chops (v.) — see frisking the whiskers.

Licks (n.) — hot musical phrases.

Lily whites (n.) — bed sheets.

Line (n.) — cost, price, money. Ex., “What is the line on this drape” (how much does this suit cost)? “Have you got the line in the mouse” (do you have the cash in your pocket)? Also, in replying, all figures are doubled. Ex., “This drape is line forty” (this suit costs twenty dollars).

Lock up — to acquire something exclusively. Ex., “He’s got that chick locked up”; “I’m gonna lock up that deal.”

Main kick (n.) — the stage.

Main on the hitch (n.) — husband.

Main queen (n.) — favorite girl friend, sweetheart.

Man in gray (n.) — the postman.

Mash me a fin (command.) — Give me $5.

Mellow (adj.) — all right, fine. Ex., “That’s mellow, Jack.”

Melted out (adj.) — broke.

Mess (n.) — something good. Ex., “That last drink was a mess.”

Meter (n.) — quarter, twenty-five cents.

Mezz (n.) — anything supreme, genuine. Ex., “this is really the mezz.”

Mitt pounding (n.) — applause.

Moo juice (n.) — milk.

Mouse (n.) — pocket. Ex., “I’ve got a meter in the mouse.”

Muggin’ (v.) — making ‘em laugh, putting on the jive. “Muggin’ lightly,” light staccato swing; “muggin’ heavy,” heavy staccato swing.

Murder (n.) — something excellent or terrific. Ex., “That’s solid murder, gate!”

Neigho, pops — Nothing doing, pal.

Nicklette (n.) — automatic phonograph, music box.

Nickel note (n.) — five-dollar bill.

Nix out (v.) — to eliminate, get rid of. Ex., “I nixed that chick out last week”; “I nixed my garments” (undressed).

Nod (n.) — sleep. Ex., “I think I’l cop a nod.”

Ofay (n.) — white person.

Off the cob (adj.) — corny, out of date.

Off-time jive (n.) — a sorry excuse, saying the wrong thing.

Orchestration (n.) — an overcoat.

Out of the world (adj.) — perfect rendition. Ex., “That sax chorus was out of the world.”

Ow! — an exclamation with varied meaning. When a beautiful chick passes by, it’s “Ow!”; and when someone pulls an awful pun, it’s also “Ow!”

Pad (n.) — bed.

Pecking (n.) — a dance introduced at the Cotton Club in 1937.

Peola (n.) — a light person, almost white.

Pigeon (n.) — a young girl.

Pops (n.) — salutation for all males (see gate; Jack).

Pounders (n.) — policemen.

Queen (n.) — a beautiful girl.

Rank (v.) — to lower.

Ready (adj.) — 100 per cent in every way. Ex., “That fried chicken was ready.”

Ride (v.) — to swing, to keep perfect tempo in playing or singing.

Riff (n.) — hot lick, musical phrase.

Righteous (adj.) — splendid, okay. Ex., “That was a righteous queen I dug you with last black.”

Rock me (v.) — send me, kill me, move me with rhythym.

Ruff (n.) — quarter, twenty-five cents.

Rug cutter (n.) — a very good dancer, an active jitterbug.

Sad (adj.) — very bad. Ex., “That was the saddest meal I ever collared.”

Sadder than a map (adj.) — terrible. Ex., “That man is sadder than a map.”

Salty (adj.) — angry, ill-tempered.

Sam got you — you’ve been drafted into the army.

Send (v.) — to arouse the emotions. (joyful). Ex., “That sends me!”

Set of seven brights (n.) — one week.

Sharp (adj.) — neat, smart, tricky. Ex., “That hat is sharp as a tack.”

Signify (v.) — to declare yourself, to brag, to boast.

Skins (n.) — drums.

Skin-beater (n.) — drummer (see hide-beater).

Sky piece (n.) — hat.

Slave (v.) — to work, whether arduous labor or not.

Slide your jib (v.) — to talk freely.

Snatcher (n.) — detective.

So help me — it’s the truth, that’s a fact.

Solid (adj.) — great, swell, okay.

Sounded off (v.) — began a program or conversation.

Spoutin’ (v.) — talking too much.

Square (n.) — an unhep person (see icky; Jeff).

Stache (v.) — to file, to hide away, to secrete.

Stand one up (v.) — to play one cheap, to assume one is a cut-rate.

To be stashed (v.) — to stand or remain.

Susie‑Q (n.) — a dance introduced at the Cotton Club in 1936.

Take it slow (v.) — be careful.

Take off (v.) — play a solo.

The man (n.) — the law.

Threads (n.) — suit, dress or costuem (see drape; dry-goods).

Tick (n.) — minute, moment. Ex., “I’ll dig you in a few ticks.” Also, ticks are doubled in accounting time, just as money isdoubled in giving “line.” Ex., “I finaled to the pad this early bright at tick twenty” (I got to bed this morning at ten o’clock).

Timber (n.) — toothipick.

To dribble (v.) — to stutter. Ex., “He talked in dribbles.”

Togged to the bricks — dressed to kill, from head to toe.

Too much (adj.) — term of highest praise. Ex., “You are too much!”

Trickeration (n.) — struttin’ your stuff, muggin’ lightly and politely.

Trilly (v.) — to leave, to depart. Ex., “Well, I guess I’ll trilly.”

Truck (v.) — to go somewhere. Ex., “I think I’ll truck on down to the ginmill (bar).”

Trucking (n.) — a dance introduced at the Cotton Club in 1933.

Twister to the slammer (n.) — the key to the door.

Two cents (n.) — two dollars.

Unhep (adj.) — not wise to the jive, said of an icky, a Jeff, a square.

Vine (n.) — a suit of clothes.

V‑8 (n.) — a chick who spurns company, is independent, is not amenable.

What’s your story? — What do you want? What have you got to say for yourself? How are tricks? What excuse can you offer? Ex., “I don’t know what his story is.”

Whipped up (adj.) — worn out, exhausted, beat for your everything.

Wren (n.) — a chick, a queen.

Wrong riff — the wrong thing said or done. Ex., “You’re coming up on the wrong riff.”

Yarddog (n.) — uncouth, badly attired, unattractive male or female.

Yeah, man — an exclamation of assent.

Zoot (adj.) — exaggerated

Zoot suit (n.) — the ultimate in clothes. The only totally and truly American civilian suit.

BONUS MUSICAL INSTRUMENT SUPPLEMENT

Guitar: Git Box or Belly-Fiddle

Bass: Doghouse

Drums: Suitcase, Hides, or Skins

Piano: Storehouse or Ivories

Saxophone: Plumbing or Reeds

Trombone: Tram or Slush-Pump

Clarinet: Licorice Stick or Gob Stick

Xylophone: Woodpile

Vibraphone: Ironworks

Violin: Squeak-Box

Accordion: Squeeze-Box or Groan-Box

Tuba: Foghorn

Electric Organ: Spark Jiver

Related Content:

A 1932 Illustrated Map of Harlem’s Night Clubs: From the Cotton Club to the Savoy Ballroom

Duke Ellington’s Symphony in Black, Starring a 19-Year-old Billie Holiday

Ayun Halliday is an author, homeschooler, and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday