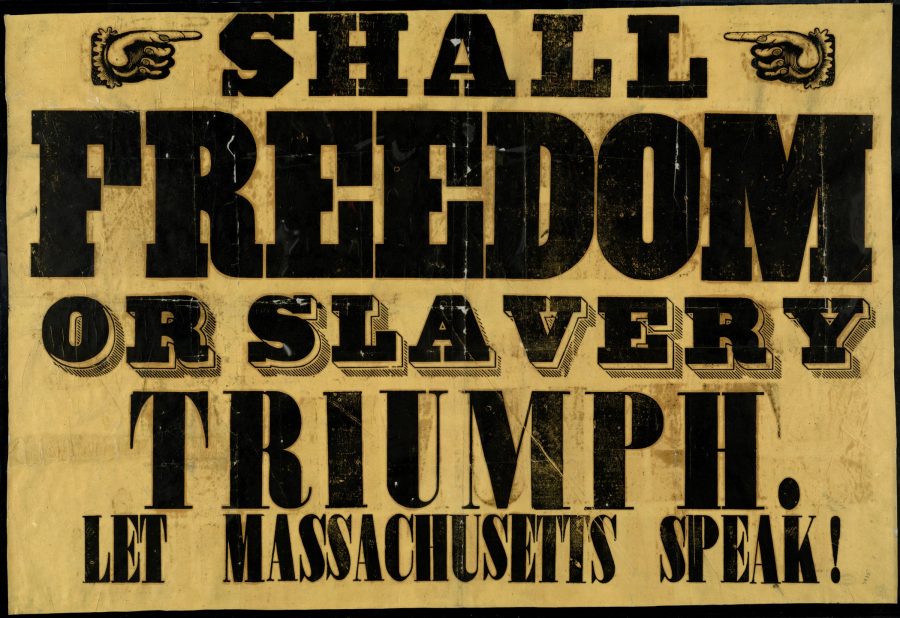

We can hardly understand America without understanding American history. Can we understand American history without understanding slavery? Many a historian would answer with an unqualified no, and not simply because they want to see Americans meditate on the sins of their ancestors: plunging into the controversies around slavery, seeing how Americans made arguments for and against it at the time, can help us approach and interpret the other large-scale legal and moral battles that have since raged in the country, and continue to rage in it today.

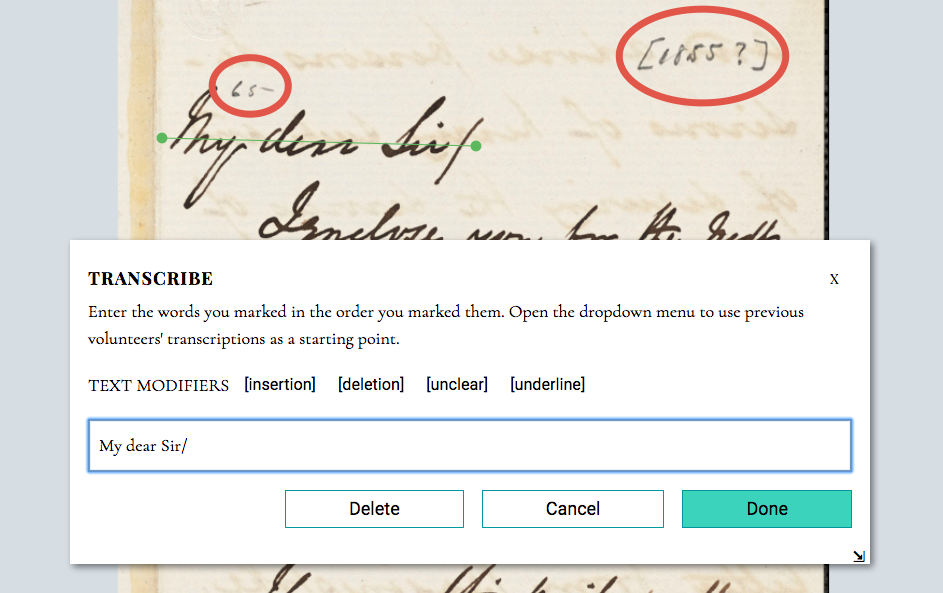

The Boston Public Library’s Anti-Slavery Collection, one particularly important resource in that intellectual effort, could use our help in making its considerable resources more readily available. “For the past several years, we have been diligently cataloging and digitizing manuscript correspondences from our Anti-Slavery collection,” writes the BPL’s Tom Blake, all of which “document the thoughts, transactions, and activities of the abolitionist movement in Boston, Massachusetts, and throughout New England.”

Now, “in order to make this collection more valuable to researchers, scholars, and historians we are pleased to announce the launch of a new website which will make these handwritten items available for you to transcribe into machine readable text.”

It’s no small job: the collection contains roughly 40,000 pieces of “correspondence, broadsides, newspapers, pamphlets, books, and memorabilia from the 1830s through the 1870s,” including the work of some of the most notable American, British, and Irish abolitionists of the day. But the combined efforts of everyone willing to transcribe a few documents, will, in Blake’s words, “allow the text corpus to be more precisely searchable and better suited for natural language processing applications – helping researchers better understand patterns, relationships, and trends embedded in the linguistics of this particular community.” Which, ultimately, will help us all to better understand America. If you’d like to lend a hand, you can create an account and start transcribing at the Anti-Slavery Collection’s site today.

Related Content:

Visualizing Slavery: The Map Abraham Lincoln Spent Hours Studying During the Civil War

The Anti-Slavery Alphabet: 1846 Book Teaches Kids the ABCs of Slavery’s Evils

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.