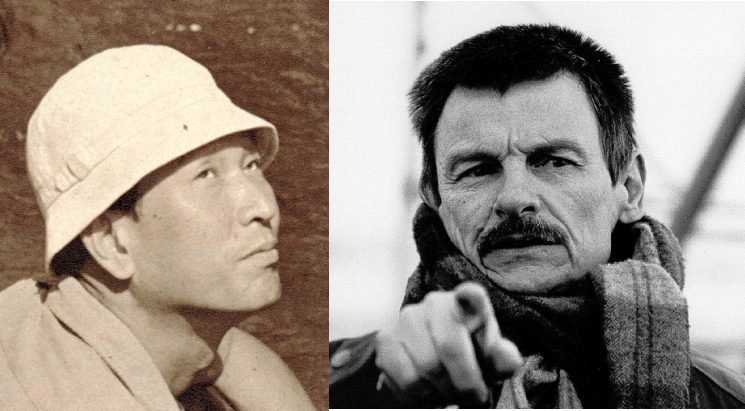

Image of Kurosawa and Tarkovsky via NPR

Though Akira Kurosawa and Andrei Tarkovsky occupy the same plane in the pantheon of auteurs — the highest one — neither their lives nor their films had much obviously in common. The older, longer-lived Kurosawa started his career earlier and ended it later, but during those cinematically glorious decades of the 1960s and 70s, the two brought into the world such pictures as Yojimbo, Ivan’s Childhood, High and Low, Red Beard, Andrei Rublev, Dodesukaden, Solaris, The Mirror, Dersu Uzala (Kurosawa’s sole Japanese-Soviet co-production, though Tarkovsky wasn’t involved), and Stalker.

They actually met around the middle of that period, when Kurosawa came to visit the set of Solaris (watch Solaris online along with many other major Tarkovsky films). “Tarkovsky guided me around the set, explaining to me as cheerfully as a young boy who is given a golden opportunity to show someone his favorite toybox,” Kurosawa writes in an essay originally run in the Asahi Shinbun in 1977 and republished at Cinephilia & Beyond.

“[Director Sergei] Bondarchuk, who came with me, asked him about the cost of the set, and left his eyes wide open when Tarkovsky answered it. The cost was so huge: about six hundred million yen as to make Bondarchuk, who directed that grand spectacle of a movie War and Peace, agape in wonder.”

But the work, as Kurosawa soon found out, merited the cost and then some:

Marvelous progress in science we have been enjoying, but where will it lead humanity after all? Sheer fearful emotion this film succeeds in conjuring up in our soul. Without it, a science fiction movie would be nothing more than a petty fancy.

These thoughts came and went while I was gazing at the screen.

Tarkovsky was together with me then. He was at the corner of the studio. When the film was over, he stood up, looking at me as if he felt timid. I said to him, “Very good. It makes me feel real fear.” Tarkovsky smiled shyly, but happily. And we toasted vodka at the restaurant in the Film Institute. Tarkovsky, who didn’t drink usually, drank a lot of vodka, and went so far as to turn off the speaker from which music had floated into the restaurant, and began to sing the theme of samurai from Seven Samurai at the top of his voice.

As if to rival him, I joined in.

For I was at that moment very happy to find myself living on Earth.

Solaris makes a viewer feel this, and even this single fact shows us that Solaris is no ordinary SF film. It truly somehow provokes pure horror in our soul. And it is under the total grip of the deep insights of Tarkovsky.

Kurosawa pays special attention to the sequence, which you can watch above analyzed by film scholars Vida Johnson and Graham Petrie, filmed in his own homeland: “What makes us shudder is the shot of the location of Akasakamitsuke, Tokyo, Japan. By a skillful use of mirrors, he turned flows of head lights and tail lamps of cars, multiplied and amplified, into a vintage image of the future city. Every shot of Solaris bears witness to the almost dazzling talents inherent in Tarkovsky.”

Like all of Tarkovsky’s features, Solaris only holds up more firmly with time and thus still enjoys revival screenings all over the world, but you can also watch it free online right now. Just get ready, when you descend to Earth afterward, to feel your own gratitude at finding yourself back here.

Related Content:

Watch Solaris (1972), Andrei Tarkovsky’s Haunting Vision of the Future

Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris Shot by Shot: A 22-Minute Breakdown of the Director’s Filmmaking

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.