Today, 133 cardinals from around the world enter the conclave to determine the next pope, during which they’ll cast their votes in the Sistine Chapel. Despite being one of the most famous tourist attractions in Europe, the Sistine Chapel still serves as a venue for such important official functions, just as it has since its completion in 1481. When its namesake Pope Sixtus IV commissioned it, he also ordered its walls covered in frescoes by some of the finest artists of that period of the Renaissance, including Sandro Botticelli, Domenico Ghirlandaio, and Cosimo Rosselli. He also made the unusual choice of having the cross-vault ceiling covered by a blue-and-gold painting of the night sky, ably executed by Piermatteo Lauro de’ Manfredi da Amelia.

No longer do the cardinals vote for their next leader under the stars, nor have they for about half a millennium. Even if you’ve never set foot in the Sistine Chapel, you surely know it as the building whose ceiling was painted by Michelangelo, lying flat on a scaffold all the while (a pleasing but highly doubtful image in the collective cultural memory).

In fact, that master of Renaissance masters didn’t touch his brush to the place until 1508. He’d been brought in by a later pope, Julius II, after having first resisted the commission, insisting that he was a sculptor first, not a painter. Fortunately for Renaissance art enthusiasts, not only did Julius II prevail upon Michelangelo, so, nearly thirty years later, did Paul III, who had him paint over the altar the work that turned out to be the Last Judgment.

In the video at the top of the post, history-and-architecture YouTuber Manuel Bravo (previously featured here on Open Culture for his explanations of historic places like Venice, Pompeii, the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore, and St. Peter’s Basilica, which was also touched by the hand of Michelangelo) narrates a 3D virtual tour of the Sistine Chapel. That format makes it possible to see not only its numerous works of Biblical art, by Michelangelo and a host of other painters besides, from every possible angle, but also the building itself just as it would have looked in eras past, even before Michelangelo made his contribution. The more you understand each individual element, the better you can appreciate this “veritable Divina Commedia of the Renaissance,” as Bravo calls it, when next you can see it in person. That, of course, will only be after the conclave finishes up: in a few hours, or days, or weeks, or maybe — a phenomenon not unexampled in the history of the church — a few years.

Related content:

Michelangelo’s David: The Fascinating Story Behind the Renaissance Marble Creation

A Secret Room with Drawings Attributed to Michelangelo Opens to Visitors in Florence

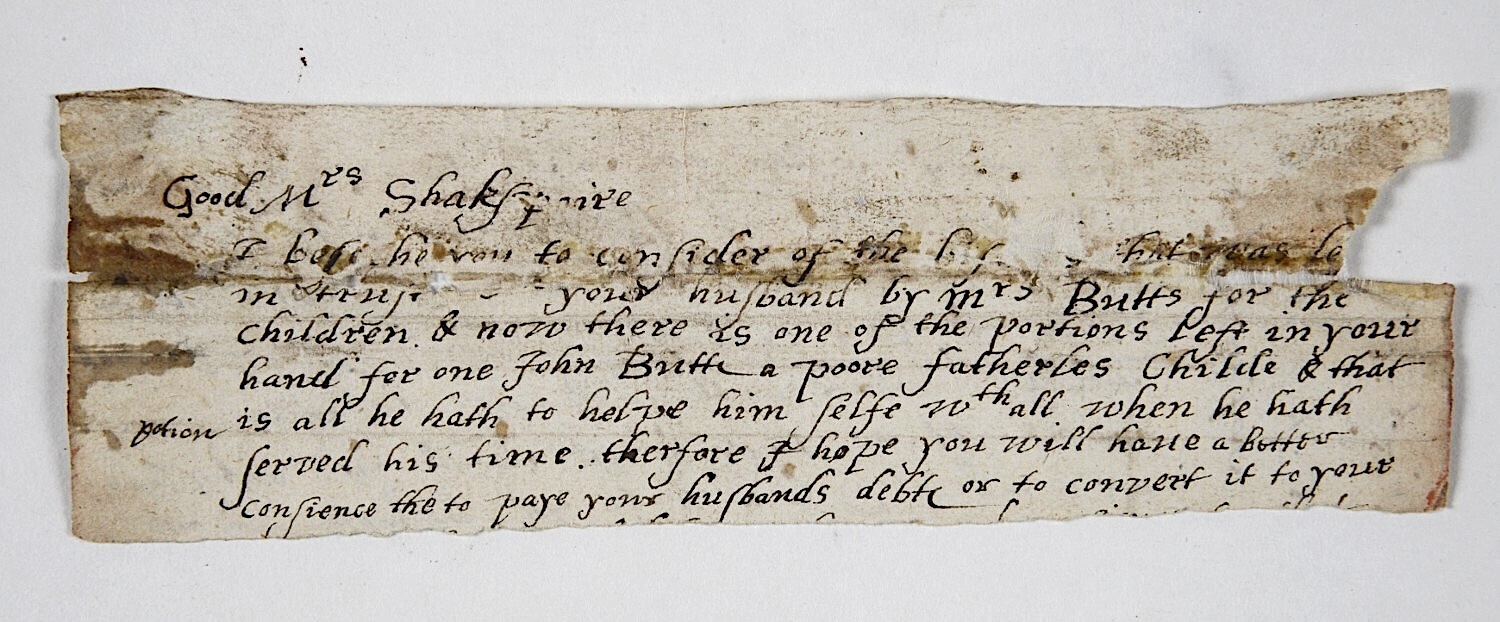

Michelangelo’s Illustrated Grocery List

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.