With 26 lines and 472 stations, the New York City subway system is practically a living organism, and way too big a topic to tackle in a short video.

Architect Michael Wyetzner may not have time to touch on rats, crime track fires, flooding, night and weekend service disruptions, or the adults-in-a-Peanuts-special sound quality of the announcements in the above episode of Architectural Digest’s Blueprints web series, but he gives an excellent overview of its evolving design, from the stations themselves to sidewalk entrances to the platform signage.

First stop, the old City Hall station, whose chandeliers, skylights, and Guastavino tile arching in an alternating colors herringbone pattern made it the star attraction of the just-opened system in 1904.

(It’s been closed since 1945, but savvy transit buffs know that they can catch a glimpse by ignoring the conductor’s announcement to exit the downtown 6 train at its last stop, then looking out the window as it makes a U‑turn, passing through the abandoned station to begin its trip back uptown. The New York Transit Museum also hosts popular thrice yearly tours.)

Express tracks have been a feature of New York’s subway system since the beginning, when Interborough Rapid Transit Company enhanced its existing elevated line with an underground route capable of carrying passengers from City Hall to Harlem for a nickel fare.

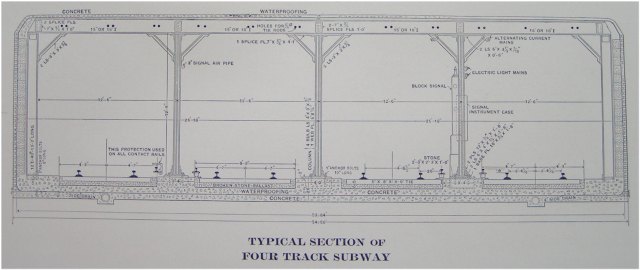

Wyetzner efficiently sketches the open excavation design of the early IRT stations — “cut and cover” trenches less than 20’ deep, with room for four tracks, platforms, and no frills support columns that are nearly as ubiquitous white subway tiles.

For the most part, New Yorkers take the subway for granted, and are always prepared to beef about the fare to service ration, but this was not the case on New Year’s Day, 2017, when riders went out of their way to take the Q train.

Following years of delays, aggravating construction noise and traffic congestion, everyone wanted to be among the first to inspect Phase 1 of the Second Avenue Subway project, which extended the line by three impressively modern, airy column-free stations.

(The massive drills used to create tunnels and stations at a far greater depth than the IRT line, were left where they wound up, in preparation for Phase 2, which is slated to push the line up to 125th St by 2029. (Don’t hold your breath…)

The designers of the subway placed a premium on aesthetics, as evidenced by the domed Art Nouveau IRT entrance kiosks and beautiful permanent platform signs.

From the original mosaics to Beaux Arts bas relief plaques like the ones paying tribute to the fortune John Jacob Astor amassed in the fur trade, there’s lots of history hiding in plain sight.

The mid-80s initiative to bring public art underground has filled stations and passageways with work by some marquee names, like Vik Muniz, Chuck Close, William Wegman, Nick Cave, Tom Otterness, Roy Lichtenstein and Yoko Ono.

Wyetzner also name checks graphic designer Massimo Vignelli who was brought aboard in 1966 to standardize the informational signage.

The white-on-black sans serif font directing us to our desired connections and exits now seems like part of the subway’s DNA.

Perhaps 21st-century innovations like countdown clocks and digital screens listing real-time service changes and alternative routes will too, one of these days.

If Wyetzner is open to filming the follow-up viewers are clamoring for in the comments, perhaps he’ll weigh in on the new A‑train cars that debuted last week, which boast security cameras, flip-up seating to accommodate riders with disabilities, and wider door openings to promote quicker boarding.

(Yes, they’re still the quickest way to get to Harlem…)

Related Content

A Subway Ride Through New York City: Watch Vintage Footage from 1905

Designer Massimo Vignelli Revisits and Defends His Iconic 1972 New York City Subway Map

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.